Charles Mingus’ greatness could be heard echoing throughout the first floor of the old Baird Hall – now Allen Hall – 45 years ago.

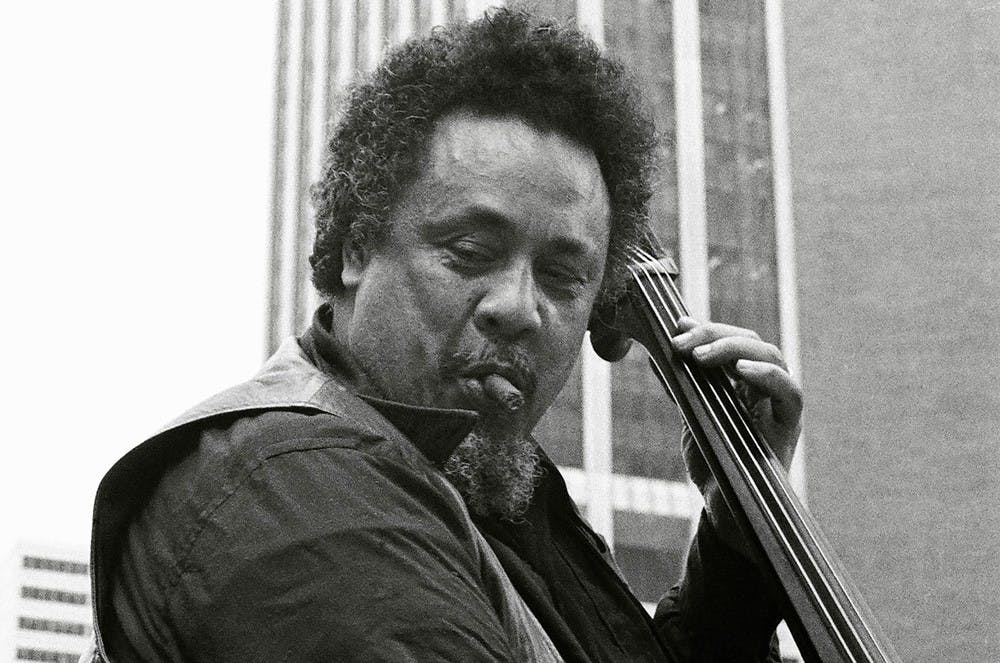

When it comes to jazz, the late Mingus is one of the first names mentioned. He was a man of many talents: a bassist, a pianist, a composer, a civil rights activist and an author.

One of his forgotten contributions however was that to education. In the spring of 1971, Mingus was invited to come to UB as the Slee Visiting Professor in Music.

One of his students in the class was Dawoud Sabu Adeyola, a bassist and protégé to Charles Mingus. Adeyola, who graduated from UB in 1976 and again in 1986, vividly recalls the moment he heard about the course from then-director of Jazz Studies Charles Gayle.

Adeyola was a fan of Mingus’ mastery on the double bass. He admired the musician’s skill, growing up with records like Mingus Dynasty and Mingus Ah Um.

Fast forward a few months later, Adeyola played bass for Mingus’ band at a party in New York City on May 21, 1971. Jazz musician Ornette Coleman, music critic Nat Hentoff and record executive Nesuhi Ertegun were all in attendance.

At first, Adeyola questioned Mingus as to why he was picked to perform at the party. In response, Mingus assured the 24-year-old bassist that he was meant for the position.

“I told him, ‘I feel a little nervous in your shoes, Charles,’” Adeyola said. “’I know all these critics and people are going to be there, they’re going to walk in and expect to see you.’ He said, ‘Don’t worry about it man, you’re going to be famous, too.’”

Mingus, similar to jazz artists like Max Roach and Miles Davis, was more than just a musician for Adeyola. Mingus and other prominent musicians tore down the walls that listeners built around jazz artists.

“They stood for something for us musically, culturally and politically,” Adeyola said. “They demanded a certain dignity and stature for themselves. Mingus’ voice was probably one of the loudest. He was very vocal about his beliefs and demanded a certain level of respect.”

Throughout his career, Adeyola has established strong ties to some of jazz music’s greatest. When he went to Buffalo’s East High School, he was part of the school’s jazz club that featured musicians like Grover Washington, Jr. and Juini Booth.

At UB, Adeyola took courses with saxophonist/composer Frank Foster of the Count Basie Orchestra.

When the director told him about Mingus’ future residency, Adeyola was skeptical at first. Once the first day came, he was the first one there to see if it was true.

“I walked into the room in Baird and there he was sitting behind the piano in the big concert hall,” Adeyola said. “A lot of people came to see if he was really going to show up. The room was full of musicians, at first.”

After a couple weeks went by, students showed up less and less often. By the middle of the semester, Adeyola was the last one left in the music composition class.

The drop in attendance did not bother Adeyola. He stayed until the very end and got to play bass alongside Mingus, who played piano.

“One of the things I learned from him was that the most complicated things – not only in music but in anything – are a bunch of simple things connected,” Adeyola said. “So he actually taught me the right way of playing a lot of his compositions and how to dissect them. You learn the simple things first then you learn how to connect them.”

Adeyola spent a lot of time with Mingus, be it walking to his place at University Manor across the street from South Campus or grabbing a bite to eat. In all his interactions with Mingus, Adeyola found the artist to be a sweet person and only wanted his students to do greatly.

“He would put out the best in you and he only associated with the best,” Adeyola said. “He had a low tolerance for unprofessionalism and mediocre performance. Even with the best musicians, he insisted that they do their best and not just rest on their reputation.”

Mingus often led a group called the Jazz Workshop. The Jazz Workshop was an ensemble where he challenged members to improve their musical abilities. On April 23, 1971, Mingus performed in the cafeteria of Goodyear Hall with his Jazz Workshop.

Thomas Putnam of the Courier Express wrote that the cafeteria’s “dim lighting” and “spots on the musicians made the atmosphere like a jazz club.” The performance was a day after Mingus’ 39thbirthday and he celebrated it in style on South Campus.

Virgil Day, a drummer born and raised in Buffalo, performed as part of the Jazz Workshop that night.

Mingus’ show at UB featured acts like saxophonist Charles McPherson and trumpeter Lonnie Hillyer backing him. The show was arranged as a closer to Mingus’ time at UB.

After the show, Day went on to perform with Mingus for a year and a half. The musician would always be an uplifting force and he was mindful of Day’s skillset on the drums.

“He was always encouraging and he knew a lot about how different drummers played,” Day said. “Mingus gave me a lot of direction and was real patient with me. He showed me how to do it and what the concept was to play that way.”

Buffalo residents also made sure they saw Mingus perform.

Joe Ford, a saxophonist born and raised in Buffalo, remembers that Mingus arrived when UB was attempting to create a jazz department. Jazz music fans rejoiced when names like Charles Mingus and musician Archie Shepp taught at the university during the early ’70s.

“If you were there and you found out about it, there’s a lot of people like me that would come out there just to see the cats,” Ford said. “It hadn’t been done at that point. They were just starting to integrate jazz into a lot of college curriculum.”

Since Mingus’ short stint in Buffalo, Ford has played on two Grammy award-winning albums with the McCoy Tyner Big Band.

Mingus’ semester teaching at UB coincided with the release of his autobiography Beneath The Underdog. After taking only one course with the music icon, Mingus offered Adeyola the chance of a lifetime.

“When the book Beneath the Underdog came out, the publisher had a book release party,” Adeyola said. “They wanted a band to play and also wanted him to be available to talk to people & sign books. At the end of the semester, he told me that I was going to be the one that would have to play and I was amazed.”

In the years that have followed the release party, Adeyola has performed and recorded with jazz acts such as Abbey Lincoln, Leon Thomas and the Ahmad Jamal Trio.

Today, Mingus’ legacy still lives on. Before the music atmosphere we have today, jazz artists like Mingus and Rahsaan Kirk challenged people’s expectations by bringing racial issues to the forefront of their music.

Adeyola believes that artists like Mingus were using their music to ask America to improve their social climate.

“His music, titles, lyrics and message that he brought was something that America really didn’t want to deal with then and might still not want to deal with,” Adeyola said. “That’s what Charles was doing 50 or 60 years ago. He was saying we have a moral and civic duty to wake our people up.”

Benjamin Blanchet is a staff writer and can be reached at arts@ubspectrum.com

Benjamin Blanchet is the senior engagement editor for The Spectrum. His words have been seen in The Buffalo News (Gusto) and The Sun newspapers of Western New York. Loves cryptoquip and double-doubles.