Elizabeth Fox-Solomon was sitting in the orthodontist’s chair when the world as she knew it changed forever.

On Sept. 11, 2001, Fox-Solomon awoke in the early hours of the morning to eat breakfast and send her roommate off for a flight to England. After leaving The Original Pancake House on Main Street in Williamsville sometime in the early morning, she went down the road to the orthodontist, where she had an appointment scheduled for a braces adjustment.

While she was laid out in a chair, the secretary came running into the room.

“Oh my God, a plane just hit the Twin Towers in New York,” the secretary cried.

At first, Fox-Solomon believed it was an accident, the result of a malfunctioning Cessna or murky conditions. But, when United Airlines Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower 17 minutes later, Fox-Solomon, just like the rest of the world, came to understand that it was no accident.

The U.S. was at war.

And her life would never be the same.

At that very moment, Fox-Solomon was one of the millions of Americans trying to gather information about what would become the deadliest terror attack ever on U.S. soil, a series of four coordinated attacks by the militant Islamic terrorist group al-Qaeda that would leave 2,996 people dead, more than 6,000 people injured and people from coast-to-coast reeling.

As the people around her shuffled in-and-out of the orthodontist’s office, Fox-Solomon knew where she needed to be: at 132 Student Union, the home of The Spectrum office, where she had recently become the managing editor.

“I remember just sitting in the chair and the first thing I thought was, I need to get back to the Spectrum office,” Fox-Solomon said in a Zoom interview last week. “That’s a crazy thing to think, but I knew I wanted to be with my friends and I knew there would be massive implications for everyone.

“I just thought, ‘I need to get back to the Spectrum office so we can respond. I need to learn what’s going on so we can report on this. We have an issue tomorrow.’”

Fox-Solomon jumped out of the chair, raced out of the office and arrived in the Student Union, where, for the next 18 hours, she and the rest of her staff furiously tried to make sense of the incomprehensible.

‘It felt really pedestrian’

Fall 2001 was primed to be a formative semester for Kevin Purdy.

After bouncing around from one major to the next and making the leap from writer to associate editor at The Spectrum, Purdy was promoted to the newspaper’s feature editor, where he not only had writing responsibilities, but was also tasked with teaching his students about the inverted pyramid and other journalistic writing techniques.

His semester was centered around the newspaper, to the “unfortunate exclusion of my schoolwork,” Purdy said in an interview. It became his career, the thing he consumed himself with when he wasn’t in class or hanging out with his friends.

Like every other burgeoning reporter, Purdy wanted to make a big splash. A front-page story with his byline in the Sept. 10 issue of The Spectrum highlighted the Student Association’s ambitious attempt to secure former President Bill Clinton as a distinguished speaker.

Located at 132 Student Union, The Spectrum office housed more than two dozen student journalists on Sept. 11, 2001.

In fact, much of the newspaper’s coverage prior to the late summer tragedy centered around the Student Association. Zealous reporters looked to highlight the SA’s “out-of-control spending,” as Purdy put it. Reporters dissected the SA ledger line-by-line, looking for superfluous items like pricey birthday cakes and needless dance parties.

Purdy says that finding out a club had spent “a lavish amount” on a pizza party would have been the type of story he would have written. That was part of a Spectrum narrative, largely grounded in fact, that the SA was spending too much on unnecessary things.

Fox-Solomon recalls a feud The Spectrum had with The Generation, UB’s now-defunct magazine that provided the campus community with an “alternative student voice,” according to its Issuu page.

The rival publications would write snide comments about each other. Once, The Generation published a story joking that the fall fest headliner would be Fox-Solomon, and that nobody would be in attendance (3 Doors Down, Everclear, Mya and Outkast all performed at fall fest that year).

“It was really just silly stuff like that,” Fox-Solomon said.

The Spectrum was also engaged in a series of reports focusing on new housing developments, from Hadley and Flint Villages to buildings going up on Skinner Road — things that at the time of publication felt significant, but in the wake of the tragedies felt irrelevant.

“College can be a little bit of a bubble,” Fox-Solomon said. “What we were focused on seems really inconsequential in retrospect. Things that once 9/11 happened felt really pedestrian and inconsequential compared to the issues facing the world.”

The Spectrum has always filled a watchdog role on campus, but sometimes, in the wake of something so monumental, that status comes into question.

“I don’t want to say it’s petty, because it was important,” Fox-Solomon said about the newspaper’s coverage prior to the events of 9/11. “It was about how we spent our money and resources, which was fulfilling The Spectrum’s role as a watchdog. It was certainly important. But it [9/11] put things in perspective once the world changed.”

‘We had to get a paper out’

Every Tuesday at 8 a.m., Purdy made the trek to the basement of Clemens Hall, where he attended a three-hour English class on the poetry of John Milton.

ENG 315: Milton was held in a windowless room and was “just brutal,” Purdy said. He was stuck in the class because he didn’t have priority registration for his courses, so in an era before widespread cell phone access and Facebook, Purdy descended to the basement for three hours of communication-less class.

That would prove crucial in the way he understood the events of that day.

As he emerged from the tunnel, his eyes still adjusting to the bright lights and his mind still scrambled from three hours of discussion about the work of a poet who had died more than 300 years earlier, Purdy was confronted by a chaotic scene: hundreds of students were crowded around small TVs, apparently watching something massive go down.

“I remember tons of people looking at two TVs in the corner, and I couldn’t even tell what was happening,” Purdy said. “All I saw was smoke.” Like Fox-Solomon, Purdy instinctively “booked it over” to the Spectrum office, where he joined the rest of the staff in watching the events unfold on a small, wheeled TV.

Purdy was still confused, as the result of his previous class: “I had just spent three hours thinking about an author who died hundreds of years ago,” Purdy said. “I was way behind most people.”

As Purdy and the rest of the staff began to make a little sense of the situation, they began delegating responsibilities. After all, there was a newspaper to print the next day, and Purdy, Fox-Solomon, editor-in-chief Emily Dalton Smith and the rest of the staff had a responsibility to fill it.

But it wasn’t just an unfilled paper that motivated the staff to turn in a paper that day.

Printing a paper gave the reporters a sense of purpose, a “feeling that we were in control of something,” as Purdy would later recall.

The Sept. 12, 2001 edition of The Spectrum featured a number of stories about the previous day’s attacks.

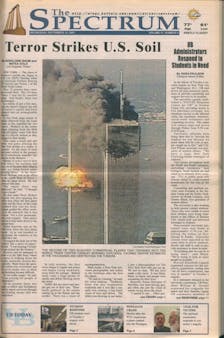

The Sept. 12, 2001 issue of The Spectrum — the publication’s first since the terror attacks the day before — features two front-page stories: one from Geraldine Baum and Matea Gold of the Los Angeles Times about the Tuesday attacks, and the other from campus news editor Sara Paulson about UB administrators — including Greiner Hall namesake and former UB President William R. Greiner — responding to students in need.

The Los Angeles Times story represents one of the only times in the publication’s history that the work of a non-Spectrum staffer graced the cover of the newspaper.

The front-page photo shows a fire at the impact zone of the World Trade Center’s South Tower and a ball of smoke rising from the top of the North Tower. Purdy recalls tension in the copy editing room, where staffers debated whether or not to enlarge the photo, which Purdy says looked like “pixelated mud.”

“We had just worked 18 hours on the paper, and the photo looked terrible,” Purdy said. “The photo went way beyond resolution. It sounds inconsequential [the debate over the photo], but that’s what happens to your brain after an event like that, even if it’s unimportant.”

Fox-Solomon wrote a story on the third page about the response of spiritual leaders and organizations. She quoted a rabbi, a minister and members of the Muslim Student Association as they responded to the unfolding attacks. She tried to capture the mood especially among Muslim students, who in later months would find themselves targeted due to their religion. Fox-Solomon, now a civil rights attorney and the chief of staff to chair Charlotte Burrows of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, wanted to shine a light on the struggles these students faced.

“We were all experiencing a horrific tragedy, and they were experiencing a horrific tragedy plus the hate, bias and fear that happens when people associate a horrific event with a group of people,” Fox-Solomon said.

Purdy wrote a story on the seventh page about Crisis Services of Buffalo, and the life-saving work they were doing to help the victims’ families cope with the tragedy. He also spoke to the Western New York chapter of the American Red Cross, which was inundated with calls from “people who desperately wanted to help any way they could,” he wrote in the story.

Arts editor Matt Mumau interviewed students for an article about the attacks; beat reporter Jamie Perna wrote about students organizing a dorm vigil; and contributing editor Stefanie Alaimo covered how UB’s Counseling Center responded to the violence. The editors also chose to print stories from The Washington Post and even ran former President George W. Bush’s complete speech following the tragedy:

“A great people has been moved to defend a great nation,” Bush said, previewing the War on Terror that was to come. “Terrorist attacks can shake the foundations of our biggest buildings (in addition to the World Trade Center, terrorists flew planes into the Pentagon and a field just north of Shanksville, PA), but they cannot touch the foundation of America. These acts shattered steel, but they cannot dent the steel of American resolve.”

In an editorial, the staff of The Spectrum implored students to do good: “When words can’t express the magnificence of horror, positive actions are what we must give to help.”

In a sign of just how hastily the newspaper was assembled, the editors ran stories about the SA kicking off monthly bar parties and concerned community members calling into WBFO to complain about housing developments at Clement and Goodyear Hall.

For a generation of student reporters whose biggest news story was the Columbine High School Massacre in 1999, the Sept. 11 attacks represented something far larger than themselves, but The Spectrum staff did what they always did: they produced a paper.

‘What are we supposed to do now?’

If the Spectrum before 9/11 was marked by stories about lavish pizza parties and housing conflicts, the publication became a source of news about the tragedy in the months following the attacks.

On Sept. 11, 2001, a series of four coordinated attacks by al-Qaeda left 2,996 people dead. The 9/11 reflecting pools in New York remember the deceased.

It was all anyone on campus wanted to talk about, Fox-Solomon said. Walk to Starbucks, traverse the Student Union or return to the dorms, and there was a student, waiting to speak about the latest developments.

“You could see it in their eyes,” Purdy said.

Everyone was processing the tragedy differently. Some, like Purdy and Fox-Solomon, buried themselves in their work: “What can I do when the world is falling apart?” Fox-Solomon remembers asking herself at the time. “It gave me a mission, a sense of purpose.”

UB is six hours away from New York by car, but many students were still affected nonetheless. Some lost family and friends; others came from areas affected by the carnage and debris. Eleven UB alumni perished in the attacks that day.

In the wake of the tragedy, everything was different in the Spectrum office. “Even if there was physical space for stories about the pizza parties, there wasn’t emotional space,” Purdy said.

Purdy and Fox-Solomon, who are now married and living in Washington, D.C., both say that the issues were very changed. The world before — easy entry into Canada for UB students, painless access to commercial flights, a trained obliviousness to massive acts of terrorism — no longer existed.

In its place is something that still exists to this day, a feeling that safety is temporary and the world can change with a blink of the eye.

“These types of events remind you that every day is not a given,” Fox-Solomon said. “You can wake up tomorrow and be told that you lost someone. People lost family members. We lost first responders. Making every day count and trying to make the world a tiny bit better, as cliché as it sounds, is so important.”

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to reflect that Purdy never wrote an article about a lavish pizza party; rather, he said that's the type of article he would have written. The Spectrum regrets this error.

Justin Weiss is the managing editor and can be reached at justin.weiss@ubspectrum.com

Justin Weiss is The Spectrum's managing editor. In his free time, he can be found hiking, playing baseball or throwing things at his TV when his sports teams aren't winning. His words have appeared in Elite Sports New York and the Long Island Herald. He can be found on Twitter @Jwmlb1.