Patrisse Cullors says those who haven’t participated in the Black Lives Matter movement wouldn’t fully understand the importance of a Black organization being nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize.

“The recognition of a Black-led movement that is challenging police violence and state violence in particular is powerful and meaningful, whether we win the prize or not,” Cullors said in a speech to UB students on Feb. 10. “It signals to the U.S. and across the globe that our movement is a movement that has always been centered [around] peace, truly.”

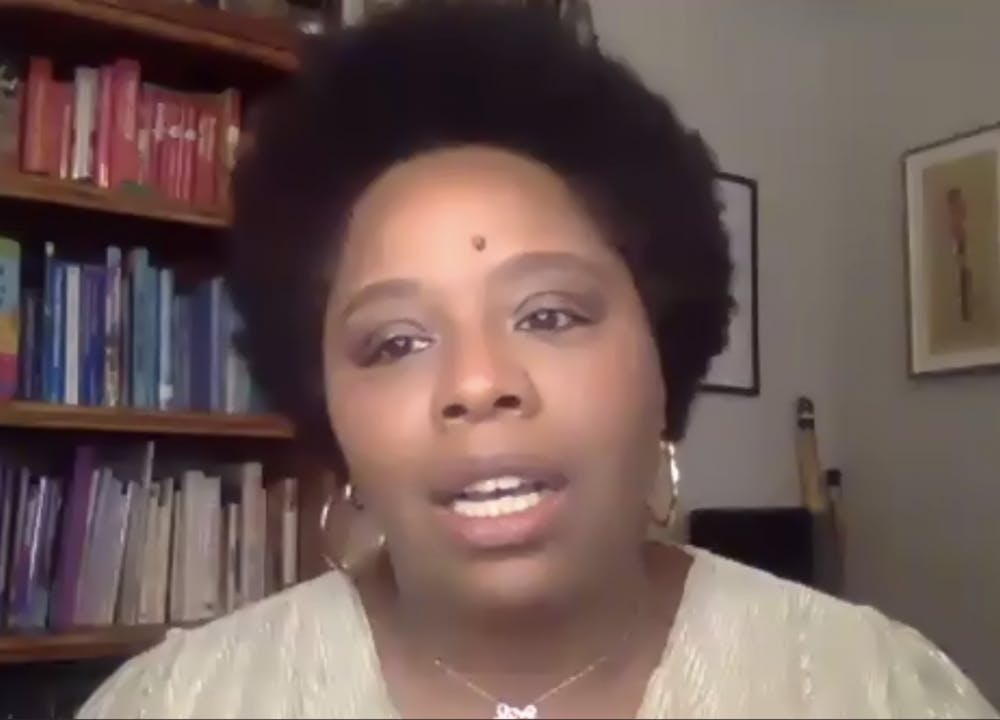

Cullors, the co-founder of the viral Twitter hashtag and movement #BlackLivesMatter and co-author of “When They Call You a Terrorist,” was UB’s 45th Martin Luther King Jr. Commemoration Keynote Speaker. In a moderated Q&A by Associate Dean for Faculty and Student Affairs and Chief Diversity Officer Raechele Pope last week, Cullors spoke to 982 participants over Zoom about the political backlash her organization has received and the experience of being nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize. She also touched on what the movement is about, how people can invest in Black communities and how to build an abolitionist future while focusing on self-care. Pope asked her own questions, while also posing inquiries from professors and attendees.

Before introducing Cullors, Pope asked viewers to acknowledge that the land UB resides on is the ancestral homeland of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, an indigeneous confederacy to Western New York. She said community members have a “responsibility to acknowledge” the history of “dispossession and forced removal” of Native populations that permitted the “growth and survival of the nation and institution.”

“In light of this history, let us take active efforts to partner with our indigenous community members and our neighbors to seek justice as we continue our work together as communities of learners, leaders and educators,” Pope said.

She called on viewers to join her in saying, ‘Black Lives Matter,’ a phrase she calls a “simple statement, a declaration, a reminder, a plea, a prayer and a demand.” Pope says these “three simple words” were turned into a global organization whose mission is to “eradicate white supremacy” and demand inclusion, while creating a space for Black “creativity, imagination, innovation and joy.”

“As [the activist and philosopher] Angela Davis said in the foreword to the book, ‘When They Call You a Terrorist,’ the seemingly simple phrase, ‘Black Lives Matter,’ has disrupted undisputed assumptions about the logic of equality, justice and human freedom in the United States, and all over the world,” Pope said.

The Black Lives Matter movement is a global organization co-founded by Black activists Cullors, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi. The co-founders say their movement aims to continue Martin Luther King Jr.’s work to uproot white supremacy and “build local power to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes.”

The movement began in July 2013 when Garza first used the hashtag in a Facebook post following George Zimmerman’s acquittal in the shooting of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin. On July 13, 2013, BLM took their fight from social media to the streets as protests launched across the country following the Zimmerman verdict.

Cullors spoke emotionally about voter disenfranchisement throughout the U.S., saying the country needs to “get rid of” the laws preventing felons from voting. She said she also noticed a lack of voter education and spoke of complaints she received about voting ballots being too complicated to understand and fill out. She says BLM has done “a ton of work” on voter education and those interested in learning more about voting can visit the organization’s Student Voter Toolkit.

She said she “never imagined” her work would get her and other members of BLM labeled as terrorists. She says “true terrorism” is what happened on Jan. 6 when protestors stormed the U.S. Capitol to disrupt the certification of the elections. Cullors said being called a terrorist is “scary” and means there are people who are trying to “suppress and repress” the movement.

From the beginning, Cullors and the other co-founders have worked to ensure the organization wouldn’t be overrun by people looking to cause “chaos and havoc.”.

“I think the repercussions of being called a terrorist, especially at the very beginning, meant there were some groups who didn’t want to work with us, didn’t want to communicate with us and who [didn’t] want to have anything to do with us,” Cullors said. “We were too controversial and that meant we were often met with death threats.”

Eleven years before co-founding the BLM movement, Cullors was a “little baby queer” fighting homophobia. Cullors has helped organize protests in Ferguson, MO against the shooting of Michael Brown and in Los Angeles, CA for the police killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd. She called the protest over the summer a “reckoning” she didn’t think she would ever see in her lifetime.

“When a state, a city, a county and a country decides that they are going to allow for people to be killed murder and murdered, without any repercussions, that we get to show up in the streets, it's our actual right to stop business as usual,” Cullors said.

During her personal protests, Cullors has experienced a sense of freedom knowing the streets “belong to the people.” She said she recognizes the feeling of “deep rage,” but also a “deep love” from those who chose to leave their homes to protest amid the pandemic.

“Our protests were not super spreader events, and our work –– when we protest and we show up for each other it’s an act of love, it’s an act of grief,” Cullors said. “They feel like this really festive generative space and they feel like a space where we get to be heard in a way that we don’t often get heard.”

Cullors believes that in order for white people to effectively fight racial injustice, they need to ask themselves how much of their “power” are they willing to give. She says the equity BLM is fighting for relies on the power everyone shares together.

“Those white supremacists, who stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6., sure, they had white privilege, but they weren’t actually fighting for their privilege, they were fighting for white power,” Cullors said. “So, are white people willing to share power? Are you willing to be in collaboration versus, ‘Okay, I gotta talk about my privilege, I get it.’”

She encourages young Black people to invest in their communities by joining organizations already investing in them. She says there is no need to “reinvent the wheel” and there are organizations already doing the work they are passionate about. But, if they don’t find one, they should start their own. She sees power in someone bringing change and uplifting their community.

“It’s part of my healing to do the work that I do, because I grew up feeling so powerless, helpless, so tossed to the side,” Cullors said. “There’s no feeling like the piercing humiliation of watching your communities be humiliated over and over again. There’s something really powerful about being like, ‘I can reclaim my experience in my neighborhood and my community.’”

Cullors encourages activists to find time to “laugh and be joyous.” She told viewers she is able to “get through” the tough times by telling herself she is going to have an amazing year and that she has a beautiful family.

“I want to see my kid, I want to be able to continue the amazing work I do, but I want to do it as a healthy human being….When the rest of the world is calling me names and is giving me death threats and I just spend time with my family, it reminds me of who I am,” Cullors said.

The 2020-21 Distinguished Speaker Series will continue to be held over Zoom and is free for those who register online.

Alexandra Moyen is the senior features editor for The Spectrum and can be reached at alexandra.moyen@ubspectrum.com and on Twitter @AlexandraMoyen

Alexandra Moyen is the senior features editor of The Spectrum.