Catherine Scharf is a UB swimmer with a secret.

She is legally blind.

But water is a great equalizer. In it, her eyes don't matter. She can be like everyone else, if not better.

She just can't see the scores when she gets out of the pool.

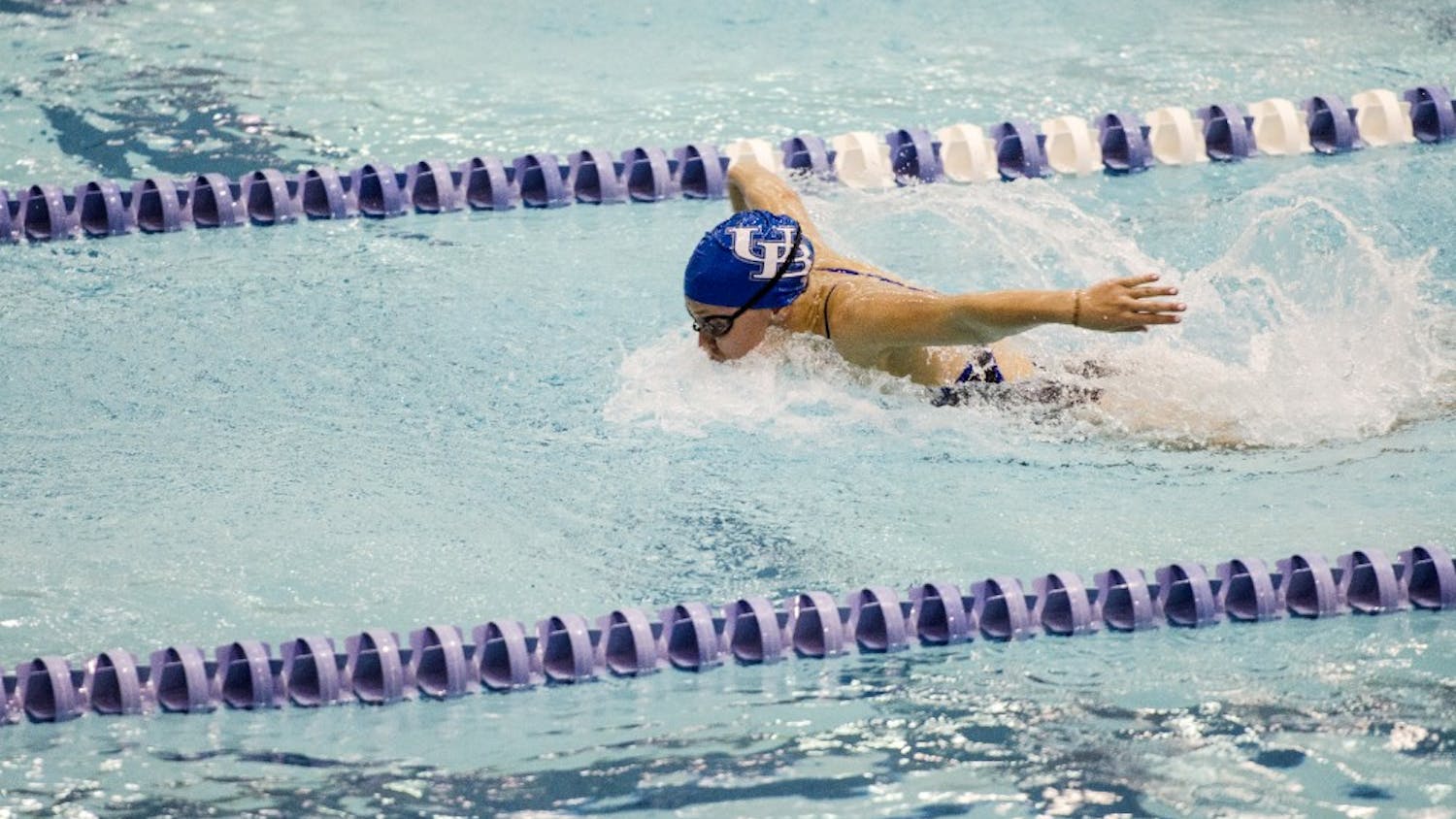

Cat, a Division I athlete and a junior health and human services major, competes as a sprinter in the 50 and 100 freestyle and the 100 butterfly on the women's swimming and diving team.

In and out of the pool, Cat refuses to be labeled "the blind girl."

"I hate that - it's not me, it's just a part of me. It doesn't define who I am, it's just something that has made me who I am," Cat said. "And I think that's still something I'm learning."

Diagnosed at the age of nine with Stargardt's disease, a macular degeneration that causes vision loss in children, Cat barely remembers what it was like to have full sight.

She cannot see the details of her mother's face, but can recognize a blurry image walking toward her as her mother by the way she holds her purse on her right shoulder, always with one hand grasping the strap. This is one of many things Cat has learned to pay attention to in order to compensate for her lack of sight. She recalls a time in high school when she was swimming and her mother was sitting in the stands.

"I said to my friend, ‘I can smell my mom. Is she here?'" Cat said.

At first, she struggled with being different. She has 20/300 vision in one speckled, hazel eye, and 20/400 in the other with or without the help of corrective lenses. That makes her legally blind, according to The American Federation for the Blind, which sets the bar at 20/200.

"I think the worst time is junior high because you start trying to figure out who you are and where you fit in," she said. "And a person who is visually impaired, with a rare impairment, doesn't really fit in with a group."

Today, Cat stands 5 feet 6 inches tall and walks with the confidence of someone much taller. But she admits getting around a campus the size of UB does pose its challenges for a visually impaired student.

"You feel confined because walking through the halls, you can't see people's faces," Cat said. "It shows what solitude you're living in when you're unable to see their expression and recognize people and you feel so vulnerable because they can see you."

Cat always excelled at sports and early on, that helped her make friends and a place for herself in her hometown of New Hartford, NY. But as her vision loss progressed, the sports she loved – basketball and soccer – became more and more difficult. She hated to admit it, but she could no longer see the ball. She knew she had to find something else.

"I started competitively swimming in sixth grade. It was the better one of all the other sports because it doesn't rely on a ball flying at you," Cat said. "Swimming put me on a level playing field with everyone else. I got to jump in and be like every other person, and rely on myself and depend on myself – and that was something that I wasn't used to."

It wasn't hard for Cat to keep her secret protected while in the pool. In the water, all that mattered was speed, strength and will.

A Section III champion in the 50 freestyle and 100 butterfly, Cat qualified for the New York State Championship meet all four years of high school.

During her junior year, her closely kept secret escaped. She tied in a vital race because of a missed flip turn and someone told a reporter that it was because she was visually impaired. The reporter wrote an article blaming the mistake on her deteriorating eyes.

Cat was enraged and wrote a letter to the reporter informing them that her condition was not to blame for her missing the wall. She added that she does not "suffer" from her eye condition – she lives with it.

Today, some may argue that Cat does more than live with Stargardt's disease – she thrives with it.

"[Cat's] just done a tremendous job for us," said Andy Bashor, head coach of UB swimming. "She is very committed to the sport of swimming and being the best she can be."

Bashor says that Cat has adapted in the pool the way she has in her everyday life.

"Suprisingly, she has one of the best flip turns on the team because I think she had to learn from a really young age that she had to practice that," he said. "That would be where the vision would hamper her, but she does that really well."

Alie Schirmers, a sophomore undecided major and Cat's teammate, says Cat makes them all better swimmers and people.

"She's always very positive and can find light in the darkest situation," Schirmers said. "She just wants to make everything around her better. And that's how I feel when I'm around her – everything should be better."

Schirmers didn't notice anything unusual about Cat when she met her last year. They were on the team together a few weeks before Cat opened up about her condition.

"That's probably the hardest thing – to know when the best time is to tell [my teammates]," Cat said. "All the freshmen each year, I sort of have to announce it to them. And I never know how to say it or how they're going to react – even though I've done it so many times, it doesn't get any easier."

When people hear that Cat is legally blind, the most common reaction is shock. Cat's condition rarely manifests itself in any outward characteristic as she walks around campus among the rest of her peers.

She has also mastered the art of fake eye contact during conversations by using her peripheral vision to guess where a person's eyes are located.

"I can never directly look at a person, or that person disappears," Cat said.

The Commission for the Blind and Visually Impaired provided Cat with a laptop equipped with Zoomtext software to enlarge print five times, to the point where she is able to see it. UB's office of Disability Services has also provided note takers and large-print tests.

Bashor does what he can to ensure Cat's success in the pool. He included a portable pace clock in the swimming budget to place in Cat's lane. Now when practicing swimming sets, Cat doesn't have to watch the person next to her to know when to push off.

"That showed me that he was really looking into something that could make it easier for me, and that was different," Cat said. "Usually people do what they can and they do what you ask for, but they don't go out of their way to help you."

But during meets, Cat is unable to see her final time.

"Swimming is an extremely demanding sport both mentally and physically, but it's also very rewarding when you look up at the clock after a race and see all of your work pay off with a best time," said Caitlin Reilly, a senior international studies major and team co-captain. "Cat doesn't get that opportunity. She is forced to rely on someone else to give [the final] time."

Despite this and other difficulties, Ellen Scharf says she has never once heard her child complain.

She said Cat had the most maternal instincts out of her brother and sister, and always looked out for her twin brother.

"Even though there is only two minutes between their births, Catherine and her twin couldn't be any different," Ellen said. "They continue to stay close, even though they have both chosen very different life paths. Catherine chose college and to be a Division I swimmer, and Adam chose to follow his dream … and is working for Disney World."

Today, Cat lives off campus with her two teammates and Ellen is exceptionally proud of the independent young woman that her daughter has become.

"Cat is an example to us all," Ellen said. "At times, I find myself complaining about little things that, most likely, I could fix if I chose to. And then I think about Cat, who faces obstacles and difficulties with a smile on her face. She conquers those obstacles because of an inner strength that I think she doesn't even know is there … she makes me very grateful that I have her as my daughter."

During her senior year of high school, the Central Association for the Blind and Visually Impaired featured Cat's story in their newsletter. They talked about her being an inspiration, as a championship swimmer with a visual impairment. A Utica paper picked up the story and interviewed Cat for a front-page article.

That was when Cat officially let her secret out – for a little while. She admitted to all – in writing – that she was legally blind. She figured that if her story could reach one person with a disability – perhaps even another young athlete going blind – it was worth it.

According to the New York State Commission for the Blind, 120,000 New Yorkers are legally blind and nearly one million live with vision loss. Twenty-five million Americans live with significant visual impairment, according to the American Federation for the Blind.

After she finally learned to accept her own condition as a part of life, Cat began educating other students about being more tolerant toward those with special needs – a quest she continues today.

Cat says a career in mental health counseling is what lies ahead. She believes that in a world of people looking out for themselves, there will always be a need for those who are willing to dedicate their lives to others.

According to Cat, living with a disability for the past 12 years played a part in the decision of where her future will take her.

"It's actually quite ironic, really. With everything I cannot see, there are so many more important things that I can see," Cat said. "I can be more compassionate and I can be more understanding or patient because I know that I've needed that from other people. I've needed other people to take time for me … [and] I want to give that time back to other people when they need it."

E-mail: features@ubspectrum.com

Blind Ambition

More

Comments