The U.S. Civil War, the Spanish Flu Pandemic and the Indian Removal Act of 1830 are heavily covered in history textbooks. These books typically narrate the causes and effects of these events on mainly Europeans and Americans, unfortunately leaving out many voices.

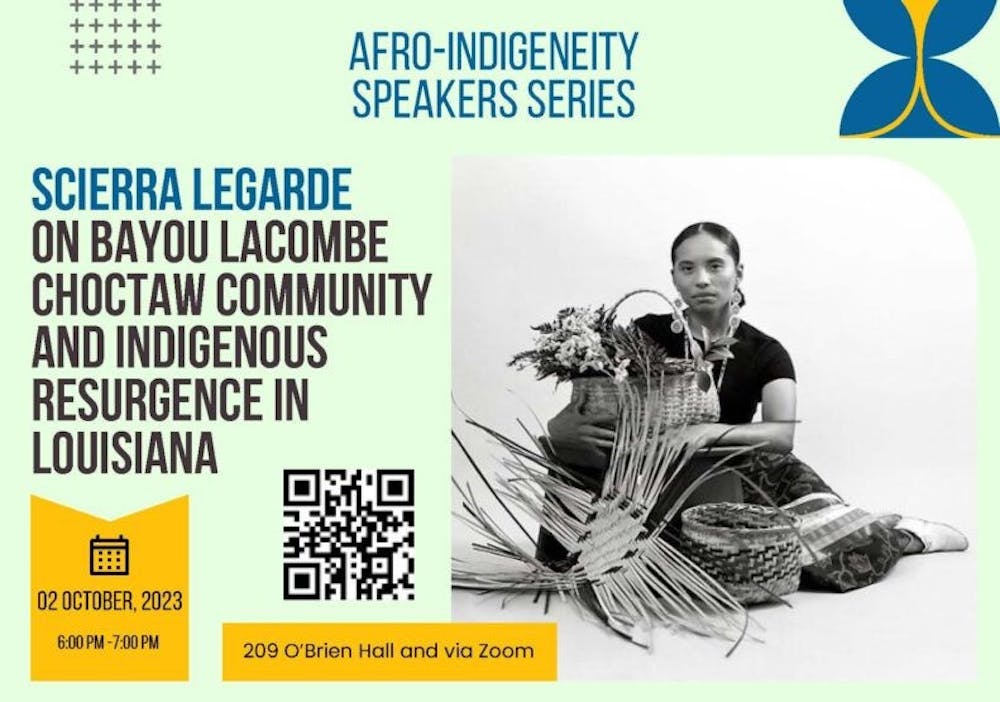

Sierra LeGarde — an Afro-Indigenous cultural activist — filled in the missing gaps when she spoke about her tribe, the Bayou Lacombe Choctaw, last week in O’Brian Hall.

As part of the Afro-Indigeneity Guest Speaker series hosted by Indigenous studies professor Robert Caldwell, LeGarde is one of many speakers dedicated to sharing their personal stories and perspectives regarding Indigenous cultures and contemporary issues.

“The reason why we host them is to show the multiplicity of experiences that Afro-Indigenous people have,” Caldwell said. “Sometimes they’re multigenerational, multiracial or first-generation, with one parent being native and the other one being Black. [These are] very different cultural contexts and experiences.”

LeGarde began her story in an era often ignored: the pre-American colonization period.

She explained where the tribe originally settled — along and to the north of the Bayou Lacombe River in Louisiana — and how this connected to the name. The word “Choctaw” stems from “Bochokwa,” with “Bocholi” meaning “to squeeze in the hand” and “Okwa” meaning “water.”

This name signifies the deep respect the tribe had for their land as they adapted to it through trade networks, agriculture and crafts. The group was devastated when Europeans forcibly removed them to Oklahoma and surrounding areas.

The audience looked at moving photos of the migration.

“The history books failed to say that we didn’t have a choice,” LeGarde said. “It was ‘go get on the train to Oklahoma or die.’ They [the Europeans] were already killing us.”

The decimation didn’t just damage the tribe’s population — which fell from one thousand to one hundred — but also its cultural heritage.

LeGarde also tackled modern racial issues, including the impact of Jim Crow laws, cultural oppression and the marginalization of native identities, which all led to “a whole new generation of people who don’t have their culture.”

“Now, in South Louisiana, there is a blurred line between what is Indigenous and what is not,” LeGarde said. “This is a conversation we have to talk about. ”

LeGarde concluded by outlining her visions for the future: reestablishing tribal relations; decolonization and re-Indigenization of history; and the revitalization of Choctaw culture within the Bayou Lacombe community.

Achieving all those goals will require telling her people’s stories, she says.

“I always stress on talking about our culture to the next generations,” LeGarde said. “It only takes one generation to forget everything about who we are and that’s it.”

The arts desk can be reached at arts@ubspectrum.com

Mylien Lai is the senior news editor at The Spectrum. Outside of getting lost in Buffalo, she enjoys practicing the piano and being a bean plant mom. She can be found at @my_my_my_myliennnn on Instagram.