Omar David has never had a black professor.

Most UB students haven’t.

UB’s Equity, Diversity and Inclusion website says the university prides itself on the diversity of its community. But black students and black faculty feel left out of the diversity conversation.

For years, UB has struggled to bring in minority faculty. That is partially because black professors are demanding higher salaries because there are so few. UB does not have the money to compete with larger universities and offer higher pay.

UB also struggles to bring in black faculty because the few who are here feel undervalued.

And many who start here, leave, because they felt isolated. Often they were the only black people working in their departments. Or they felt the university didn’t put enough money, time or resources into black studies.

And students – many of whom come to UB for its diverse student population – feel discouraged because almost none of their professors look like them.

In a city as diverse as Buffalo and at a time when racial tensions are exploding across the nation, students say they expect more racial equality from UB. Black people make up 38.6 percent of the Buffalo population, according to the U.S. Census. Yet as of fall 2015, out of 2,513 faculty at UB, only 98 were black, according to UB Spokesperson John Della Contrada. That’s 3.8 percent. Out of those 98, only 41 were tenure track, which brings the total down to 1.6 percent.

David, a senior biological sciences major, feels having a black professor would have been inspirational. He thinks he would have aspired for greater leadership roles at UB if he had seen someone who looked like him and shared the same struggles achieve success.

But David never got his wish.

In the past 10 years, black faculty have continued to leave the university. Data from Teresa Miller, vice provost for Equity and Inclusion shows black faculty continued to decline from 2005 to 2015.

Miller has spent the last three years trying to recruit faculty of color. Faculty acknowledge Miller has worked hard, but say the university as a whole needs to take more responsibility in hiring black faculty.

Della Contrada said the university employs 202 state-supported staff “the second-largest race/ethnicity group, after whites for staff.”

“So that’s basically janitors and Campus Dining food workers…” David said. “That doesn’t make the lack of black faculty any better, if anything that makes it worse because it’s just placing more black people in more marginalized menial work.”

Addressing black issues

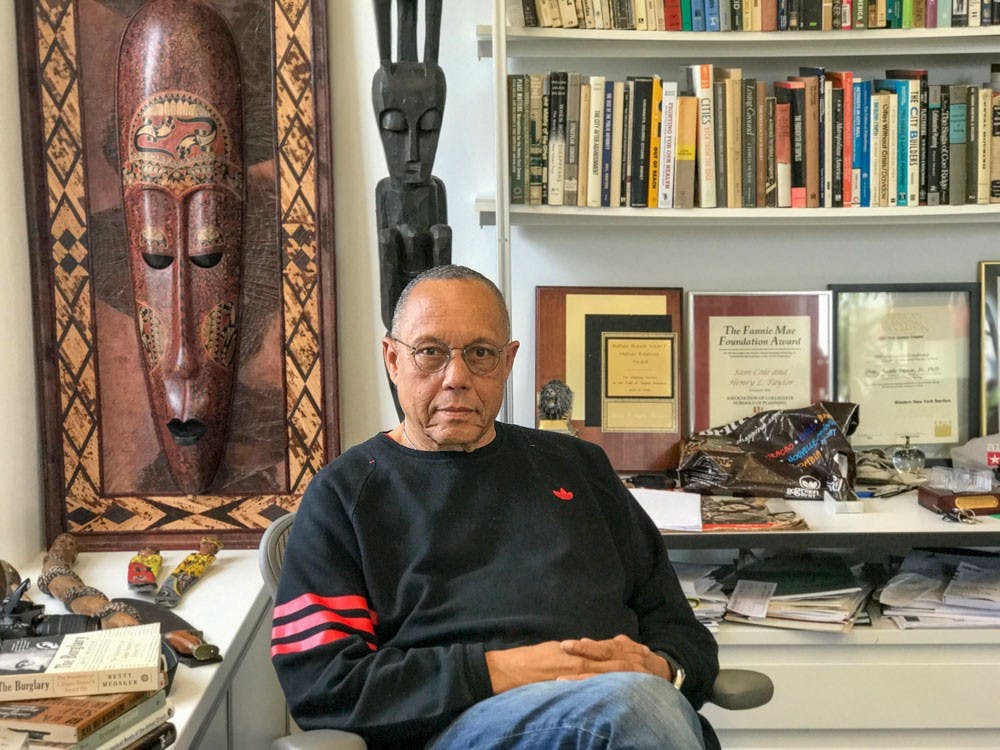

The number of black faculty at UB is “beyond disgraceful,” said urban and regional planning professor Henry Taylor.

Taylor said the university’s failure to do something about the lack of black faculty is a form of systemic racism. Such failure, he said “under develops” the black community by not allowing the African American studies program to evolve.

“The African American people were people that this country had a special responsibility to in the sense that they had been brought here as slaves, stolen from their country, imprisoned on their homeland and brought here to work,” Taylor said. “The university has a huge responsibility to [us] and I think the university has failed in a very miserable way.”

Taylor said black people get nothing, “absolutely zero” for suffering as a result of slavery.

When Taylor first came to UB in 1987, one of the university’s priorities was addressing issues black people faced, he said.

He was hired at the university specifically to help design a public service infrastructure that would connect the university to a larger urban community. He addressed these issues with then-UB President William Greiner and visited his house so often people thought he was Greiner’s relative.

Taylor also helped redevelop the University Plaza area, located across from South Campus.

He said administrators slowly began to feel race was too divisive of an issue and thought it needed to be minimized. Taylor said he was among the minority who felt race needed to be grappled with, talked about and placed at the forefront of university discussions.

Taylor said the university often boasts about its diversity by placing minority groups like Asians in the forefront so the campus looks diverse.

“There is no diversity because the university no longer has the commitment to dealing with the exploitation and oppression of black people,” Taylor said. “In the old days, we used to call that window dressing, when you get enough black people around just to say ‘there they are,’ but that’s not authentic and that’s not legitimate.”

Lack of blacks vs Buffalo demographics.

Blacks are the second-largest ethnic group in Buffalo, second only to whites, who hold a 50.4 percent majority.

“We live in a city that’s close to 50 percent black and Latinx, and yet we have not a single major initiative that’s focused on that,” Taylor said. “We have a Global Health Equity Institute that doesn’t even have a focus on the African American population.”

Taylor said despite the high concentration of blacks, the university continues to prioritize addressing refugee and immigrant issues over black issues.

“And my response is ‘seriously?’ Why don’t you try moving the health equity needle in Buffalo? And why would you ever focus on the refugee population and not have a focus on the African American population whose health indicators are horrendous? Who face an enormous level of inequities in comparison to whites and they don’t even make your cut? Seriously people?” he said.

Taylor said there has been a dramatic decline in tenure-track black faculty in the past 25-30 years and the university continues to lose the small number of tenure-track faculty embedded on the campus.

“When you talk about faculty... the only thing that counts in a really meaningful way – and I don’t wanna disparage anyone – are those individuals who are full time and on tenure track because unless you’re full time and on tenure-track lines, you’re not providing instructional activities that are leading to degrees,” he said.

Taylor said the U.S. has a responsibility to create opportunities for black people to achieve their larger freedoms.

These larger freedoms, he said, aren’t the same as small freedoms like the right to vote, the right to speak or the right of social mobility.

“The larger freedoms are our human rights. The right to a high-quality education. The right to an employment that allows us to earn a livable wage. The right to live in safe and wholesome neighborhoods. The right to have high quality health care. The right to have nutritious food. These are our human rights. And education is an anchor human right. So that is the right that we have not yet been given or granted,” he said.

Faculty members who are not of color like transnational studies Professor Carl Nightingale agree that the lack of black faculty is a problem.

Nightingale said the university hasn’t done an adequate job of retaining faculty of color and the transnational studies department continues to lose more minority faculty. He said retaining more faculty of color should be a “major institutional priority.”

Recruitment of black faculty

The desperate need for the university to find a solution that brings in more faculty of color is an issue that keeps Teresa Miller up at night.

She has a daughter who’s a freshman in college and she evaluates diversity through her eyes. She worries that UB students of color don’t have enough professors who look like them.

As a black woman, in her role, she says people expect her to have a certain level of insight on issues facing people of color. They expect her to bring her own racial experiences to the table to help increase the university’s diversity.

She doesn’t think the resolve to hire black faculty has wavered, but UB’s strategy to hire them has changed in the last 30 years in light of widespread criticisms of initiatives like affirmative action.

Because of this, she says the university can’t use race as the sole criteria of hiring.

“The legal definition of affirmative action changed in the last 30 years, so there’s been an attack on the way race gets used in the hiring process so we’ve had to change the hiring process of people of color,” she said.

The university responded by changing its strategies for minority faculty recruitment.

Miller carved out a 10-step “strategic plan” to hire more culturally diverse staff.

The plan encourages the university to advertise for positions in areas with more people of color to gain more diverse applicant pools and take part in minority cluster hiring. It advises to reduce hiring barriers against people of color by training faculty to eliminate implicit biases.

Miller also regularly goes to conferences and sees how other universities hire faculty of color, and she carves out a plan based on her discoveries.

But many faculty of color drop out of these searches early, Miller said.

Other black faculty don’t want to come to the university because they don’t see people who look like them on campus.

Miller said colleges like Columbia University, Yale University or University of Michigan invest $30 to $50 million in recruiting faculty of color.

UB doesn’t have that money.

“Underrepresented minority faculty are demanding much higher starting salaries because there are fewer of them so it's scarce and we often compete with schools that can pay a lot more,” Miller said.

While the university struggles to recruit blacks, Miller said the university continues to draw international, non-black faculty from across the globe in management, engineering and the sciences.

“I think the demographics of the nation and the state have changed over the last 30 years so the diversity of the non-white population has become greater in New York State than the rest of the nation,” said Craig Abbey, associate vice president and director of Institutional Analysis.

Miller doesn’t agree that the university’s commitment to hiring diverse faculty has shifted; she says the commitment has only gotten stronger.

“I don’t agree that our commitment is much less today, I think our commitment has grown. This office being created and being staffed and built out. That’s a commitment, it’s a commitment of resources to really make a difference,” she said.

How lack of black faculty affects students

The lack of diversity isn’t just limited to faculty; it also extends to the student body. Out of 28,444 UB students, only 1,881 students are black.

Students of color yearn to see people who look like them teaching in the classroom. Many students said they grew used to being the only black people in their classes, but they found it puzzling that many African American studies professors at UB were white.

Miller went to college at Duke University in North Carolina and said she only had one black professor.

“I say to people all the time, students are our clients and they want to see people who can relate to their experiences who are role models and mentors and it’s absolutely important,” Miller said.

While Taylor agrees a black professor could bring a unique perspective that a white professor couldn’t, he says the color of people’s skin doesn’t qualify them to teach black studies.

“I’m a firm believer based on my experiences that black faces in high places don’t mean a thing unless their ideologies and viewpoints are emphasizing change,” he said.

Taylor said there are some black people he wouldn’t want anywhere near UB students and within the black community there can be an ideological divide.

“There are some black people that I know through these buildings that I wouldn’t want anywhere near our black students and I certainly wouldn’t want them trying to teach them anything about the black experience,” he said.

He’s come across white scholars who have deep understandings of that experience and he says he would be happy to call them colleagues.

Taylor feels the university is responsible for finding and attracting “outstanding black scholars” but feels UB has never done that for its black studies program. He feels UB’s black studies program is one of the weakest in the country.

Black faculty departures

Lakisha Simmons, a former global gender studies professor, left UB to teach at the University of Michigan earlier this year. She found it difficult to teach in a department where she was the only black woman.

When she first came to UB, she loved that there was a core group of young faculty of color and she became very close with them and built “a strong community.”

That strong community of faculty of color dwindled over the six years she taught at the university.

“Things got really difficult for me a couple of years ago when the fate of global gender studies and African American studies seemed uncertain and I feel like at that time, there were messages that those studies were not valued,” Simmons said. “I feel like things changed with the current dean and Provost Miller but at that point, it was already almost too late. And if you feel that what you do is unimportant to the university for a certain number of years... it hurts your morale.”

At University of Michigan, she says black faculty are more valued because more money is invested in programs like black studies and global gender studies.

Another reason Simmons left UB was because black studies, global gender studies and African studies didn’t have their own department and were under the transnational studies department.

“It’s never perfect because there’s bias against people of color and women in the workplace... it’s not limited to the university. In the current political climate, where you go to school does make a difference but it’s difficult wherever you are,” she said. “It’s difficult to be a black person working wherever you are.”

Finding solutions

Simmons believes the university has to make a “huge push” for cluster hires in order to rectify the issue of lack of black faculty.

Miller said she is currently working with College of Arts and Sciences Dean Robin Schulze to cluster hire faculty of color.

The Spectrum reached out to Schulze three weeks ago, but her chief of staff said she could not fit an interview into her busy schedule.

Simmons said she sees Miller and many deans support recruiting black faculty, but she still doesn’t know if there’s urgency across the university, particularly from President Satish Tripathi and Provost Charles Zukoski.

“I think it’s getting to a point that it’s going to take drastic action just to get back to where UB was five years ago so there has to be some kind of targeted hire,” Simmons said. “Either you're a school that's recruiting faculty or you’re one that’s losing them because there are only so many professors of color.”

Taylor said he gets offers to teach at different universities often, but chooses to stay at UB.

“I’m not trying to run away from problems, I’m trying to solve them,” Taylor said.

Ashley Inkumsah is the co-senior news editor and can be reached at ashley.inkumsah@ubspectrum.com