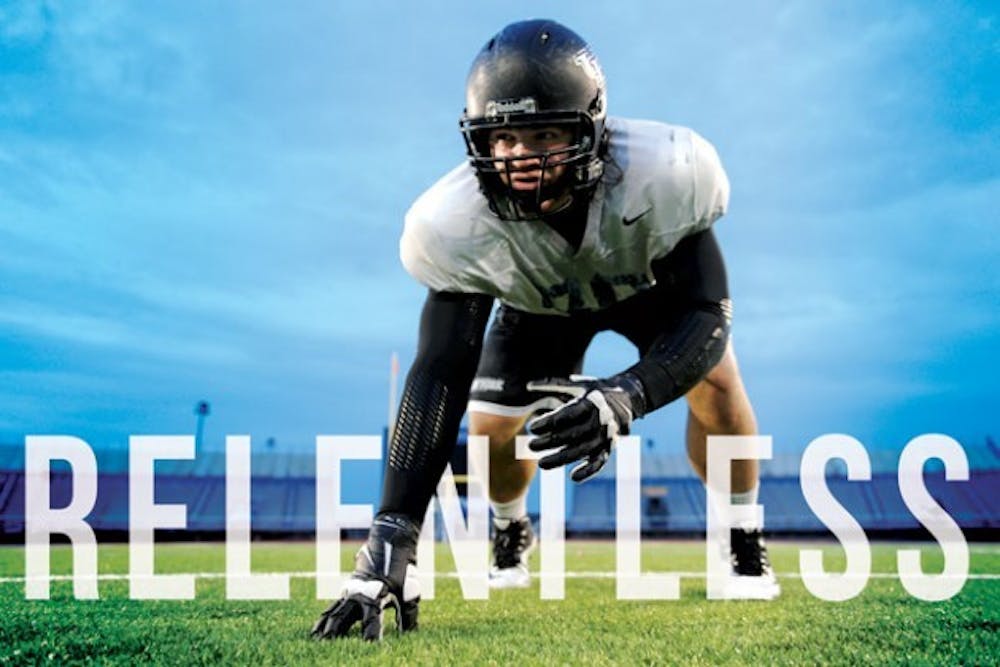

If Kristjan Sokoli had to describe a nose tackle in one word, it would be “relentless.”

He said there are bad plays and good plays for the position. A good play is when there’s a wide gap between the center and guard. This allows him to swipe away the center’s hands and get into the backfield to make a tackle for a loss.

Here’s what Sokoli calls a ‘bad play’ – or what normally happens when he lines up on the defensive line for the Buffalo football team.

You think the center is going to block you. And as you go to attack the center, the center doesn’t block you. The guard comes and ear holes you. Your tackle’s coming inside to try and get into his gap but he can’t get into his gap because you’re in his gap now because you got ear holed by the guard. So not only do you not know what’s going on, you got ear holed, and the tackle steps on your foot and then you just want to scream out of anger.

It’s what comes with being a nose tackle. Few would call it a glorified position. For every play Sokoli ends up with a sack or tackle for a loss, theere's 50 plays he gets his foot stepped on. It’s why he has to be relentless.

“You just got to keep fighting,” Sokoli said. “Even though sometimes it might not make a lot of sense you got to keep fighting and then you get to enjoy the better moments of it when it does make sense.”

Sokoli did the same after immigrating to the United States from Albania at the age of 9.

He didn’t speak a word of English – and was ridiculed for it. He didn’t have the same luxuries as other kids. His father struggled to make money as an apartment complex janitor. He had to convince his parents football was safe even as the injuries piled up. Edmir Sokoli, his cousin, mentor and the person who showed him what American football was while trying to keep Sokoli on the right path, went to prison for armed robbery.

Nothing made sense.

But Sokoli kept fighting to get through.

He became so good at English he helped his parents learn the language. He earned a full scholarship to a Division I university. His father is now superintendent of that apartment complex.

Sokoli is enjoying the better moments.

“I’m like, ‘What am I doing here? Some Albanian guy?’” Sokoli said. “I was in Albania, now I’m playing in front of 20,000 fans in Buffalo, New York in college football.”

Sokoli played his last game in a Buffalo uniform on Nov. 28, and hopes his next football game will be on an NFL field. It would be yet another accomplishment for a player whose journey to the gridiron spans almost half the globe.

“Being from my background, I’ve had to get through different obstacles and people telling me I can’t do this or people giving me the cold shoulder,” Sokoli said. “I’ve always tried to just stick to the plan and stick to what I know is right. Knowing that I’m some kid from Albania, that’s definitely a motivating factor.”

***

It’s a late October practice at UB Stadium. Sokoli and the rest of the starters run sprints down to the end zone for more than 10 minutes. After he gets done with his own conditioning, Sokoli doesn’t stop to rest. He walks over and stands in front of the reserves that are running condition drills themselves.

Sokoli claps and offers words of encouragement to his teammates – most of whom he towers over. He’s 6-foot-5 and 293 pounds. His high school coach called him “Moose.” His former Buffalo teammate and roommate, Dalton Barksdale, said Sokoli eats five meals a day. He stands out on the field by not only his size, but also by his long brown hair that flows out the back of his helmet.

Sokoli stands and yells until the final player finishes and the final whistle blows. His drive comes from his father.

“Coming from a different country, the work ethic is a little bit different, especially when you see your parents go through somewhat hard times,” said Andre Reid, Sokoli’s high school trainer. “His father is an extremely hard worker and a good example of what needs to be done in America.”

At 7 a.m., Sokoli’s father, Gjon, would travel a mile underground. He wouldn’t come out until 3 p.m. He did this for seven years in Albania.

Gjon said his father was a “happy communist” who did not allow his children to go to school, but instead sent them to the mines for work after mandated military service. Gjon eventually got a job working for a bank in 1996.

Then the economic collapse happened.

After the communism period ended in Albania in 1992, the government engaged in several failed Ponzi schemes that caused the Albanian Rebellion of 1997. With the banks in disarray, Gjon became involved in monetary exchange.

Sokoli can tell “a lot of crazy stories” about his father’s experiences, but admits it may not be the time or place. To say monetary exchange in Albania in the mid 1990s was a gray area might be a bit of an understatement.

“At that point it was a little … I don’t think anyone had a license to do it … It was right after communism and everything was like … It was very little control from the police so everyone kind of did their own thing,” Sokoli said, pausing as he struggles to describe his father’s job.

Sokoli always remembers his father having a lot of money on him – Gjon would carry as much as $10,000 of his clients’ money at one time. He traded for different country’s currencies depending on what the demand was. He would have to trust the people around him.

“There were times when he had to just throw $10,000 worth of money to his friend,” Sokoli said. “He had to throw a bag to him and say, ‘Hey I’m going to pick that up tomorrow. I can’t carry it right now because of the situation.’ He had to trust his friends and he had to be a trustworthy person and he had to be consistent in what he did every day.”

At 6 years old, Sokoli would help his father count as much as $20,000.

But it wasn’t his father’s money – it was his clients’. Sokoli said his father was making good money for an Albanian, but Gjon wanted more for his family – or what he called a “better opportunity” for his children.

Sokoli said there was a lot of inequality in Albania. He says if you didn’t already have a lot of money, it was “tough to make it.” Sokoli admits there is inequality in the United States, but said it’s still not as bad as Albania.

“It’s not like [in the United States] when, ‘Hey, you do good in school, you go to college, you’re going to find a way to make it.’ That’s not always the case back there,” Sokoli said. “My dad saw that the better future was in America … He made the decision to give up everything he had built in Albania for a tougher climb but in the long run a better life in America.”

Gjon saved enough money for a plane ticket and left for the United States in 1997, leaving behind his wife, Gjyste, and his two sons, Kristjan and Mark. He had to work if the rest of his family was going to join him.

Gjon did not speak a word of English. His only education was eight grades of schooling from a third world country.

“So you can imagine there wasn’t a lot of employment opportunities,” Sokoli said.

Gjon worked as a maintenance worker for a Bloomfield, New Jersey apartment complex. He lived in the basement of the building with other workers. He made $45 a day and “lived off bread and milk.”

“I’d be happy to do any job to get money to eat for myself and save some money to send back to my country to give food to my kids,” Gjon said.

Gjyste was able to come to the United States in 1999, leaving Sokoli and Mark – who is three years younger than Sokoli, without their parents. The brothers moved in with their uncle and waited for their opportunity to join their parents.

Sokoli said the process is about more than just having money for a plane ticket; it’s about the “paperwork process and lawyers.”

“People kept saying, ‘Soon, soon. It should happen soon.’ But it was tough, you’d have to wait,” he said. “The legal process is challenging and it’s not always easy. For some people it works out and for some it doesn’t.”

Three years after his father originally left Albania, the paperwork came through for Sokoli and Mark to join their parents in the United States. Sokoli remembers running for joy with his brother.

***

Sokoli doesn’t think he’ll ever be a true American.

He says it’s because he’s proud of where he comes from. He listened to Albanian music in the hotel room on road trips. A large Albanian flag hangs on his bedroom wall. Albanian is the first language in the Sokoli household, and it’s the language he uses to speak with his parents on the phone – which confuses his roommates at times.

“If you listen to Soko talk to his parents, you’ll think they’re fighting, and then at the end he’ll be like [in English], ‘All right, love you. Talk to you later,’” Barksdale said.

But it’s clear living in the United States for 14 years has ‘Americanized’ the nose tackle.

He’s fluent in English and has no hint of an accent. He wants to work on Wall Street. He can tell you in detail how his favorite team – the New York Yankees – lost last night.

“Derek Jeter was up with two outs. If he’d hit a homerun it would have been an epic moment but he struck out in three pitches,” Sokoli laments.

Sokoli may never feel like a true American, but he says he realizes the opportunity living in the United States has given him.

“I’m damn proud to be an American because of what this country and has provided for me and my family is huge,” Sokoli said. “It’s completely changed our lives and the opportunities we have for the better tenfold.”

His first American experience was eating macaroni and cheese while on the plane to the United States. The Albanian brothers were “amazed” by it, as Mark puts it.

After getting lost in JFK International Airport, Sokoli and Mark found their parents.

“Finally, to have that moment when you come together as a family and you’re legal, you’re stable and you know you can live in this place as long as you do the right things,” Sokoli said. “It was a very big feeling of accomplishment for the four of us as a family.”

He found that his and his family’s struggle would not end when arriving in the United States.

***

Albanians think people find money everywhere in United States, according to Sokoli. Gjon still gets calls from friends back in Albanian asking for money.

“They make America to be better than it actually is,” Sokoli said.

Sokoli had heard fantasies about life in the United States while growing up in Eastern Europe, but he found America was different from the stories.

Life was supposed to be easier. His family was supposed to be finding money lying in the streets. Instead, they lived in the Bloomfield apartment complex his dad worked in. They didn’t go on vacations like other families and Sokoli didn’t wear the same clothes or have the same toys as his friends.

“We weren’t as well off,” Sokoli said. “We had to grind. It wasn’t easy.”

On top of his families’ financial struggles, classmates made fun of Sokoli every day because he couldn’t speak English. There were a “a lot of hard moments.”

English as a second language classes helped him, but Sokoli said a person doesn’t learn English by sitting in a classroom for an hour a day. He learned English mostly by listening to it, whether from his classmates and teachers or just hearing it on TV.

A few months after arriving in the U.S., Sokoli could do his homework by himself.

“I say, ‘What are you doing?’ He said, ‘Father, I am doing homework.’ I say, ‘How are you doing?’ He said, ‘The teacher is doing very well with me,’” Gjon recalls. “And little by little he start to teach me to speak English.”

Within a year of arriving in America, Sokoli could hold down a conversation. Within two years he said he could “definitely understand everything,” and by middle school he was being told, “Wow, you don’t even have an accent.”

Some people tell him he still has one.

“I don’t know what they’re talking about,” he says.

Even his families’ financial situation improved. They have a house not far from the apartment complex. Gjon is now superintendent of the apartment.

“He says he still works there but every time I go there he’s just driving his truck car around the place, managing I guess,” Sokoli said. “But no, I give him credit. He’s worked hard and he deserves it. He deserves for it to be a little easier now.”

Sokoli’s scholarship to UB would be the accumulation of the grind his family went through.

“Through adversity and through sticking with it and doing the right things and staying with the plan we’ve come a long way and I’m very proud of my family,” Sokoli said.

***

Sokoli amassed 95 tackles, 15 for losses, and 2.5 sacks in his four seasons in Buffalo. He was a key component as a mainstay on Buffalo’s defensive line during the Bulls’ 2013 bowl season.

But for the first nine years of his life, Sokoli had never even heard of American football.

“Soccer was everything in Albania,” Sokoli said.

During the years he lived with his uncle while his parents were in America, Sokoli and his cousins would play soccer – making their own soccer jerseys and drawing up scenarios of scoring the game-winning goal.

His cousin, Edmir, was the person who first introduced him to the sport that would eventually get Sokoli a full ride to a university.

Edmir, or ‘Eddie’ as Sokoli calls him, is five years older than Sokoli and came to the United States with his parents a few years before Sokoli.

Edmir was a standout at Bloomfield High School. And he was tough. He broke his leg playing running back, so he moved to nose tackle. He even played fullback and guard when the coaches asked him to. Sokoli said Edmir played “fearless.”

“Man, I just wanted to play as hard as he did,” Sokoli said. “I just wanted to be as fearless as he was on the field.”

Edmir gave Sokoli a ride to his first-ever football practice. As Sokoli got out of the car, Edmir gave “words of wisdom,” telling his 13-year-old cousin to play, run and hit hard.

Sokoli needed the words of encouragement. He says he was the worst kid on the team. He had the athleticism, but he was behind his peers who had played pop warner or had at least seen football on T.V. before.

Sokoli wasn’t getting much support at home, either.

His parents thought football wasn’t safe. They had read about all the injuries and “negative stuff,” about the game. Sokoli remembers battling his father every night.

“They were just completely against it to the point where they were telling my brother, ‘You absolutely cannot do this. You’re not going to live in this house if you do,’” Mark said. “The way [Sokoli] put it, he was saying he’d rather not be living or be on this Earth than not play football.”

Gjon and Gjyste’s concerns weren’t unwarranted. Sokoli suffered a multiple injuries playing for Bloomfield high school, including a sprained wrist, a broken collarbone and two hairline fractures in his arm.

Sokoli’s family told him, “Hey we told you so, this is a bad sport.” After his second hairline fracture, Gjyste told her son something is telling him to stop playing football.

“He said, ‘Mom, I will break my arm, and my leg and everything in my body and I’m not stopping football,” Gjyste said.

Throughout all of the injuries and doubts, there was one person who Sokoli’s says had his back: Edmir.

He was the person you needed to hear when you were down, according to Sokoli. Edmir would say things like, “Hey cuz jus stick to it, man,” or, “Injuries are going to happen, you’re going to get better, you got a lot of potential in the sport.”

Edmir mentored Sokoli on more than just the game of football.

He would make sure his younger cousin was staying at home the night before his high school games. He would text Sokoli at 1 a.m. on Friday nights saying “Cuz, don’t get caught up in the moment. Don’t do anything that’s going to jeopardize what you want the most.”

“He was always trying to keep me sharp,” Sokoli said.

Edmir also introduced Sokoli to the trainer who proved to be vital in Sokoli earning a Division I Scholarship: Andre Reid.

Gjon and Gjyste were still apprehensive about the dangers of the sport, but after meeting Reid they agreed to pay him to train their son. It was the moment the Sokoli family finally accepted football.

“When I met Kristjan he said, ‘I want you to help me get a full ride to a university and I want to see if we can make it all the way to the NFL.’ I said, ‘If you listen to me, we’re going to make it happen,’” Reid said.

And with Reid improving Sokoli’s skills, Sokoli did get a full ride. He was playing Madden in his basement when he got a call from UB offering a scholarship.

Sokoli couldn’t stop moving. He said he was “on cloud nine,” as he paced around his parent’s house feeling relief, excitement, joy and accomplishment. He asked himself if it all really happening, or if it was just a dream.

His parents were equally skeptical. They asked him if he was sure it was really Buffalo on the phone.

“When you come to this country and you work for minimum wage and you work hard for so long, making it big kind of seems not realistic,” Sokoli said.

But one of the most influential people in Sokoli getting the scholarship was not there to enjoy the moment.

It was Edmir who introduced Sokoli to the sport football and his trainer. It was Edmir who had driven him to his football practices when his family disapproved. It was Edmir who kept him focused on the goal and “on the right path.”

But Edmir would never see his cousin play a single college game. That’s because he did exactly what he had tried to tell his cousin not do, and has been inside a New Jersey county correctional facility for the past five years.

***

On Aug. 18, 2009, a few weeks before Sokoli was set to begin his senior season at Bloomfield High School, Edmir and another man entered Rachel Jewelers in Kearny, New Jersey with the intent to rob it.

Edmir’s accomplice, John Derosa, got into a physical altercation with storeowner Xavier Egoavil. Derosa, who had been convicted of manslaughter in 1980, opened fire and killed Egoavil. Edmir and Derosa fled to a getaway car that was waiting outside.

This is according to Hudson County prosecutors, who charged Derosa with murder, felony murder, weapons charges and armed robbery. Edmir and the getaway driver pleaded guilty to armed robbery in April 2010.

Sokoli went on “human auto pilot.” Bloomfield head coach Mike Carter pulled Sokoli into his office the day after Edmir was arrested.

“Moose, are you OK? Are you going to be all right?” Carter asked his star senior.

Sokoli shrugged it all on off, told Carter, “Yeah, coach.” He said he dumbed the situation down. He thought to himself, Yeah he went to jail, he’s going to be all right, he’s going to come out. But Sokoli felt differently on the inside.

“What really hurt me was that he had worked so hard with me and had been there for me so much to get to where I had gotten to at that point. Just when he could see the result, he had to go away,” Sokoli said.

Edmir tried to keep Sokoli on the straight and narrow with football. He told his cousin not to get caught up in the moment. Sokoli said Edmir “got caught up in the moment” when he entered Rachel’s Jewelers on Aug. 18, 2009.

Edmir still talks to Sokoli on the phone from prison once a week.

He still offers his cousin words of wisdom, saying, “Whenever you think you have it bad and you’re thinking about making a mistake and doing something you know is not the right thing to do, just think of where I’m at and be thankful for what you have,” according to Sokoli.

Sokoli said football was his “rock” in high school. He says it keeps “you on a one-path focus.”

“As a kid I feel like you have so many opportunities to veer off the right path,” Sokoli said. “You can go into drinking and drugs and excess of things you shouldn’t be doing, but I feel like football was a good foundation for me because it was like, ‘Well, I shouldn’t do that because I know what I want to get to.’ I always had the dream of playing in the NFL. I knew that to play in the NFL I had to go to a good school and I knew to go to a good school I got to get good grades and it was a foundation.”

***

Sokoli spent his first month after his final UB game training at Pinnacle Fitness and Training Center in Bloomfield. Reid, who once helped Sokoli get a D-I scholarship, owns the facility. Now he’ll try to get Sokoli a minicamp invite.

He played in the Medal of Honor College All-Star game on Jan. 10. Sokoli played the three technique, which he says is more natural for his build. He had two tackles for losses and a pass defended.

Sokoli is currently training at St. Vincent’s training facility in Indianapolis, Indiana. He’s preparing for UB’s pro day at Ralph Wilson Stadium field house in March, where he’ll be able to showcase his skills in front of NFL scouts.

If he doesn’t land himself on an NFL roster, Sokoli wants to put his management degree with a focus in finance to use and work on Wall Street. He said counting thousands of dollars at a young age in Albanian probably influenced that desire.

He likes the “big shark eats little shark” mentality of Wall Street. Sokoli says it’s not that he likes injustice; he just likes competition. He wants a performance-based atmosphere where people want results and aspire to do great things.

He makes the New York Stock Exchange sound like the gridiron. But what Sokoli would really like to do is investment banking.

“A lot of guys who get into that have 4.0 [GPA’s] and are from Harvard or Yale and I’m a just a 3.1 student-athlete from the University at Buffalo who was born in Albanian. Who’d put me in investment banking?” he laughs.

But then again, who would put an Albanian immigrant who’s never heard of the game onto a football field?

email: sports@ubspectrum.com