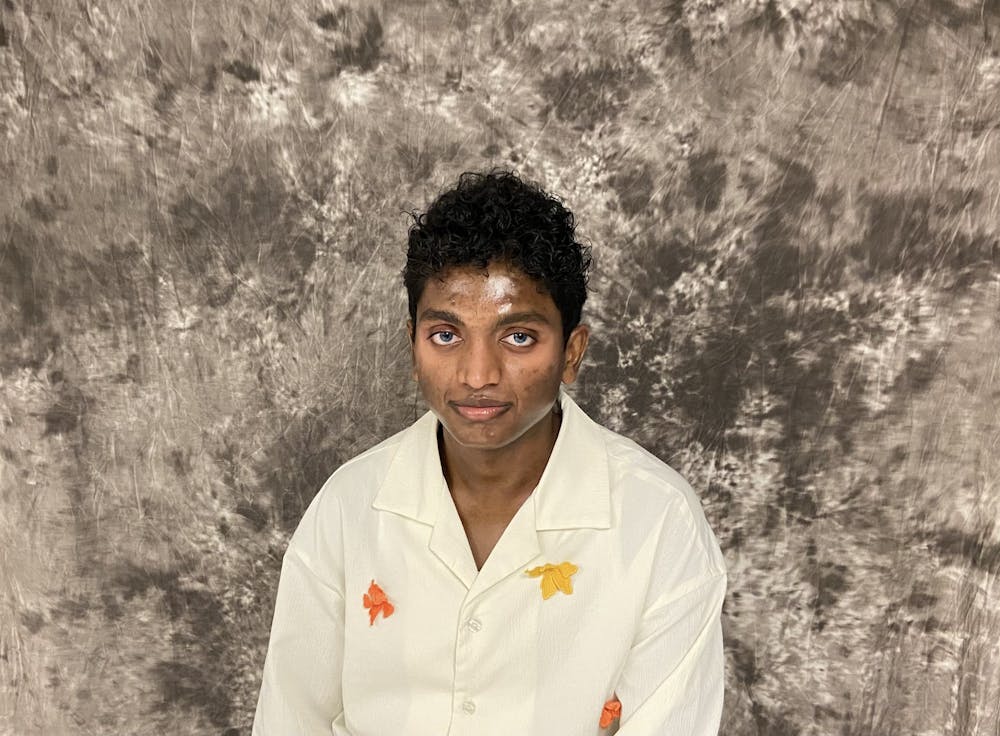

At the age of 13, Amrith Mariappan received devastating news.

His doctors diagnosed him with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), a rare form of blood cancer that affects an individual’s bone marrow.

About a year later, Amarnath Mariappan, Amrith’s brother, was diagnosed with the same condition.

After his diagnosis, Mariappan struggled to find quality treatment in his home country, India. Due to the combination of a small donor pool and doctors’ unwillingness to take a risk, Mariappan was unable to receive a bone marrow transplant, a risky operation that had the potential to cure him.

Mariappan left India for the United States in January 2021.

“[The doctors] told me to stay in India, but I was so adamant,” Mariappan, now a second year Ph.D. student and aerospace engineering major at UB, said. “I wanted to pursue my studies, so I came to the U.S.”

Mariappan would go on to found a UB chapter of the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) in the fall 2023 to help others with MDS — only after securing a donation himself.

While studying at UB in 2021, Mariappan’s health declined, prompting him to seek medical attention. He learned that his blood levels were too low and he needed an immediate transfusion. Mariappan eventually wound up at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center.

From there, the cancer center searched for potential donors who matched Mariappan’s human leukocyte antigen type. After waiting a year, the cancer center matched him with a woman in Poland.

But Mariappan wasn’t excited when he heard the news.

“I didn’t feel anything,” Mariappan said. “It’s probably because I’ve been dealing with it for more than 10 years. I just got tired of it.”

In June 2022, Mariappan underwent a life-saving bone marrow transplant. Mariappan’s doctors had to completely kill his immune cells in order to transplant the donor cells.

After the transplant, Mariappan was required to obtain a caregiver for 100 days of recovery. Since his parents were unable to travel to the U.S. from India, Mariappan was out of options — until his friends came to his assistance.

“I couldn’t find anyone who could be a caregiver,” Mariappan said. “Then, five of my friends said they would step in and [take turns being my caregiver] every week.”

Seven months after Mariappan’s transplant procedure, his brother underwent two transplants in India. Despite the doctors’ efforts to keep his brother alive, both transplants were unsuccessful.

Unfortunately, Amarnath Mariappan died from sepsis. He was 22 years old.

After his brother passed, Amrith Mariappan honored Amarnath’s life by becoming an NMDP ambassador and forming a chapter at UB.

“I wanted to work with the NMDP to get more people in the registry,” Mariappan said. “So in the future, nobody will have to lose their lives because they don’t have a perfect match.”

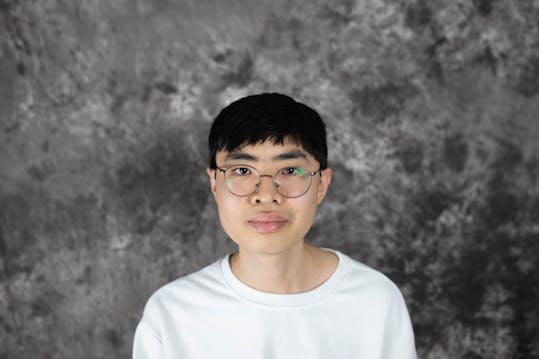

During the early stages of the chapter, Mariappan recruited members and potential donors by giving lectures and meeting with organizations on campus. After hearing Mariappan’s story at a lecture, Dominique Betterbed, a third-year medical student and secretary of UB’s NMDP chapter, was motivated to join the cause.

“[Mariappan’s] case is a miracle,” Betterbed said. “It just speaks a little bit to how science can really save somebody’s life and how a program like this is so important to bring people together for a good cause.”

The chapter’s goal is to diversify the donor registry by recruiting students. Getting a match with someone of the same ethnic background increases the odds of the match being perfect.

Currently, the chances of finding a match based on ethnicity are 29% for Black people, 47% for Asian and Pacific Islanders, 48% for Hispanic or Latinos, 60% for Native Americans and 79% for white people.

Betterbed was surprised by how disproportionate the figures are for minority populations.

“Coming from a biracial background, that was something that stood out to me,” Betterbed said. “I wanted to be a part of diversifying the registry to bring [down] those numbers of minorities without a match.”

To get students to join the donor registry, the chapter has tabled across campus and collaborated with other student organizations. Students have to fill out an eligibility survey and then — if eligible — swab the insides of their cheeks for a DNA sample.

The chapter then sends those swabs to the national registry. If students are notified that there’s been a match, they have to certify with their primary doctor that they’re healthy enough to donate before going to a transplant center.

“A common misconception is that whenever people hear ‘transplant,’ [they think it means] losing an organ,” Mariappan said. “But as far as bone marrow transplant is considered for the donor, there is no losing [an organ].”

Depending on the patient’s location, donors would have to travel to the transplant center. The NMDP covers all medical and travel expenses for donors, as well as lost wages.

Donors may experience side effects after donating, but the majority are expected to make a full recovery.

As a current ambassador for the NMDP, Mariappan plans to continue to work with the nonprofit organization after he graduates from UB.

If he could go back, Mariappan would give his 13-year-old self words of encouragement.

“I was so timid back then, but now I’m not anymore,” Mariappan said. “I would say, ‘You’re so brave, and I’m very proud of us.’”

Students who are interested in joining UB’s NMDP chapter can fill out this form.

Jason Tsoi is an assistant features editor and can be reached at jason.tsoi@ubspectrum.com

Jason Tsoi is an assistant features editor at The Spectrum. He is an English major with a certificate in journalism. During his free time, he can be found listening to music and watching films.