Shep Gordon’s parents brought their son to a Queens Greyhound station in the summer of 1964 and loaded his bags onto a midnight bus to Buffalo.

Once Gordon, a ‘68 alum and retired music mogul, got off the bus, he and a friend decided to hitchhike all the way to Buffalo State College, where they heard “beautiful women” attended school.

And when they arrived at what they believed was Buff State, they saw a giant fence. The two were confused, but in true teenage-boy fashion, still hopped over the barrier to get to the girls.

But instead of finding themselves surrounded by “beautiful women,” they found themselves in a mental institution.

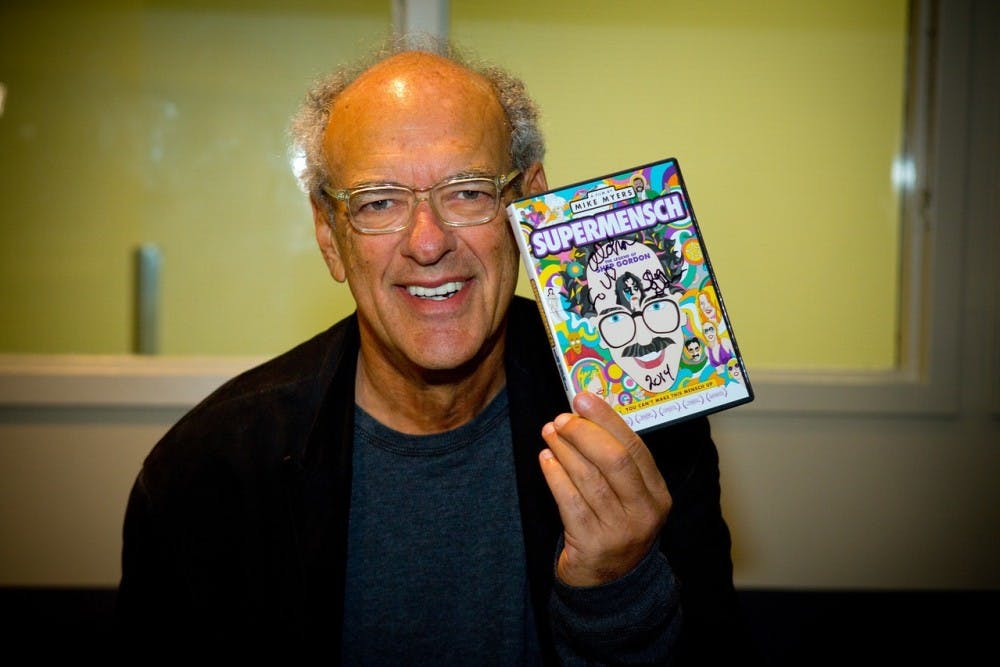

Gordon couldn’t resist laughing at this punchline, which he delivered like a comedy pro at 73 years old. And even in a documentary about his life, “Supermensch: The Legend of Shep Gordon,” Gordon refers to his college experience as “the best years of his life;” years where he was politically active, experimented with drugs and pulled historic pranks.

To most, however, these years wouldn’t top making Alice Cooper famous, creating the concept of a “celebrity chef” or bringing the Dalai Lama to one’s alma mater; all of which Gordon has accomplished and mastered. Those years paid off too, as Gordon now resides in Maui, fully retired from the management business, with the exception of Cooper.

And all of the LSD, acid, marijuana, codeine and cough syrup that Gordon toyed with during his college years and in his early career haven’t hindered his memory.

If anything, they’ve enhanced it.

“Taking the drugs was a part of the experience of liberating yourself,” Gordon said. “We’d get really stupid a lot of times because we didn’t know why we were doing them. It was very innocent in a way, where it turned into something not innocent later in life.”

Gordon, who lived off campus throughout his time at UB, said his drug use was more exploratory than anything else. But when he wasn’t exploring drugs, he used his college years as a way to stay politically active. He publically burned draft cards to protest the Vietnam War and said this activism played a role in shaping his career.

“I had the feeling that, ‘Wow, this worked. The war ended. You can affect history,’” Gordon said. “That’s the way I felt. … That gave me the confidence to go out after Buffalo and do the kind of things that I did because I really felt like, for the first time, I was an important part of what happened on this planet.”

But Gordon didn’t just impact history, he and his pranks specifically, impacted Buffalo history.

In his early years at UB, Gordon was a recruiter for fraternity Sigma Alpha Mu and sought UB freshmen in Allentown. While recruiting, he met several biology students, all of whom were laughing over the name “Thallus of Marchantia,” or the scientific name for a fern’s sex organ.

Gordon and his new friends realized that the name “Thallus of Marchantia” funnily sounded like the title of a head of state in a foreign country. Armed with this realization, Gordon and friend Artie Shein decided to organize a prank visit to Buffalo for the “Thallus of Marchantia,” and earned the attention of The Buffalo News in the process.

Protestors packed outside the Buffalo airport in 1964 to protest the arrival of the anti-semitic “Thallus of Marchantia,” a made-up ruler that Gordon and friends invented to prank the city of Buffalo.

“One thing led to another, and we decided, let’s see if we can pull a hoax on the city of Buffalo,” Gordon said. “We got a friend in New York City to go to the United Nations Western Union office, and send a telegram to the mayor of Buffalo that the ‘Thallus of Marchantia’ was making his first royal visit to America, and he has family that lives in Buffalo.”

Gordon thought the telegram would be the end. In reality, it was only the beginning.

Protestors packed outside the Buffalo airport in 1964 to protest the arrival of the anti-semitic “Thallus of Marchantia,” a made-up ruler that Gordon and friends invented to prank the city of Buffalo.

Schein flew to New York in order to fly back to Buffalo wrapped in a sheet as the “Thallus of Marchantia,” prolonging the prank even further. And Gordon had another idea and sent another telegram.

“[We sent another telegram] and said, ‘How can you let the Thallus of Marchantia come to Buffalo? He’s the most anti-semitic ruler,’” Gordon said. “Over 1,000 people showed up at the airport [protesting the arrival].”

The Spectrum’s archives highlight Shein and Gordon’s prank and the eventual hundreds of protestors it brought out to the Buffalo airport in late 1964.

The Spectrum’s 1964 coverage of the “Thallus of Marchantia” hoax.

“I realized you could create history. You didn’t have to wait for it,” Gordon said.

But Gordon didn’t prank alone in Buffalo. Gordon’s friends Dan Alterman, a ‘68 alum and Alan Brandt, have all remained close since their college days and find time to regularly meet up and reminisce.

The trio went out often and helped give Gordon his first taste of the Buffalo music scene.

Alterman said he, Gordon and Brandt used to listen to rock music at the Pine Grille on Jefferson Street, occasionally catching a glimpse of music legends Chuck Berry and Sam Cooke.

“We didn’t study very much until finals,” Alterman said. “It was only after we left Buffalo that we realized we were smarter than we thought.”

Brandt laughs when thinking back to his UB days with Alterman and Gordon. He says he “certainly didn’t realize the value of education until” after graduation, but he thinks the bond the trio shared in Buffalo is the most important takeaway.

“The friendships we’ve made we still have, and it’s a testament to the closeness we shared [in Buffalo]”

Creating history

After leaving a humorous mark on friends in Buffalo and graduating with a degree in sociology in 1968, Gordon flew to Los Angeles with the goal of becoming a probation officer.

Instead, he found Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison at a “fleabag” motel.

The music legends bonded with Gordon and became some of his first friends after college. But Gordon wasn’t starstruck.

“It was a very different time and they didn’t make a lot of money,” Gordon said. “It was fairly limited … they didn’t have real ego issues. They were real people.”

But they carried real problems. Before they all passed away at a young age, they led Gordon to his first massive client in management: Alice Cooper.

Gordon formed Alive Enterprises in 1969 and set out to make Alice Cooper a rock superstar. He had Cooper perform naked, throw live chickens into his crowds and even create traffic jams — caused by cars with Alice Cooper billboards on top — to make his first client a household name. He did all this without ever having a contract with Cooper.

Gordon later oversaw the release and production of titular albums like “Love it to Death,” “School’s Out” and “Billion Dollar Babies.”

But like Gordon’s friends in Los Angeles, drugs and alcohol took their toll on Cooper and eventually strained the duo’s relationship.

“The last thing I ever wanted to do was work hard to make money for someone who took the money and killed themself,” Gordon said. “I told him that I didn’t want to help kill him. For two years I didn’t see him. He ended up in the hospital and called me, and we got together again like a day hadn’t gone by.”

Cooper led Gordon to managing the likes of Teddy Pendergrass, Luther Vandross, Anne Murray and Rick James. But even this wasn’t enough for Gordon, who later pounced on a newfound passion for cooking decades later.

Gordon noticed that chefs rarely received compensation for their fame. So in the ‘90s, he became the first to represent some of the biggest names in the culinary world like Emeril Lagasse, Roger Verge and Wolfgang Puck. Lagasse famously said that Gordon is responsible for creating the concept of a “celebrity chef.”

Using an old connection with CNN founder Reese Schonfeld, Gordon offered his roster of chefs to be featured on the newly launched Food Network.

Gordon always kept strong roots, and UB was no different.

When his newest cooking venture exploded, his connections in the cooking world led him to not only feed the 14th Dalai Lama, but to serve on the board of the Tibet Fund, His Holiness’ nonprofit organization that preserves the cultural and national identity of the Tibetan people, according to its website.

In the early 2000s, UB representatives reached out to Gordon to facilitate bringing His Holiness to UB. Gordon then flew to Buffalo, met with four administrators and had an idea.

Gordon, using leverage through his position on the nonprofit’s board, would administer Fulbright Scholarships to Tibetan students. He told UB administrators that, if Buffalo houses the most Tibetan students compared to other schools, His Holiness will “break down the doors” to tell those students how proud he was of them.

And it happened.

On Sept. 21, 2006, the Dalai Lama spoke to a crowd of 30,000 at UB Stadium for one of the most historic days in school history.

“It was a beautiful day,” Gordon said. “The weather was beautiful. The audience was beautiful. He was beautiful and it was a beautiful moment.”

And Gordon’s connections made the beautiful day happen, which is a side of the story that UB rarely shares when discussing the historic day.

But Gordon seems O.K. staying behind the scenes, as long as he can make somewhat of a difference.

Shep Gordon (right) stands next to UB friends Dan Alterman and Gus Reichbach.

“Shep really wants his life to be a service so that he can make your life a little bit better,” Alterman said. “He’s someone who asks, ‘what can I do for you that will help you enjoy your experience [in life]?’”

He recognizes that “every human is different” and hopes his journey -- which started with him hopping fences to get to girls and now stands with him lying on a hammock in his Hawaii retirement home -- serves a model for graduating students unsure about their futures.

“I wake up in the morning and react to what the planet gave me. I think over-stressing about ‘What am I going to do?’ or ‘Who am I going to be?’ will only lead to forcing yourself into something that isn’t natural,” Gordon said. “Question yourself about how much you’re questioning yourself. … Always gravitate toward what makes you happy.”

Correction: The description of the Tibet Fund is according to its website.

Brenton Blanchet and Brian Evans are editors and can be reached at arts@ubspectrum.com.

Brenton J. Blanchet is the 2019-20 editor-in-chief of The Spectrum. His work has appeared in Billboard, Clash Magazine, DJBooth, PopCrush, The Face and more. Ask him about Mariah Carey.

Brian Evans is a senior English major and The Spectrum's senior arts editor.