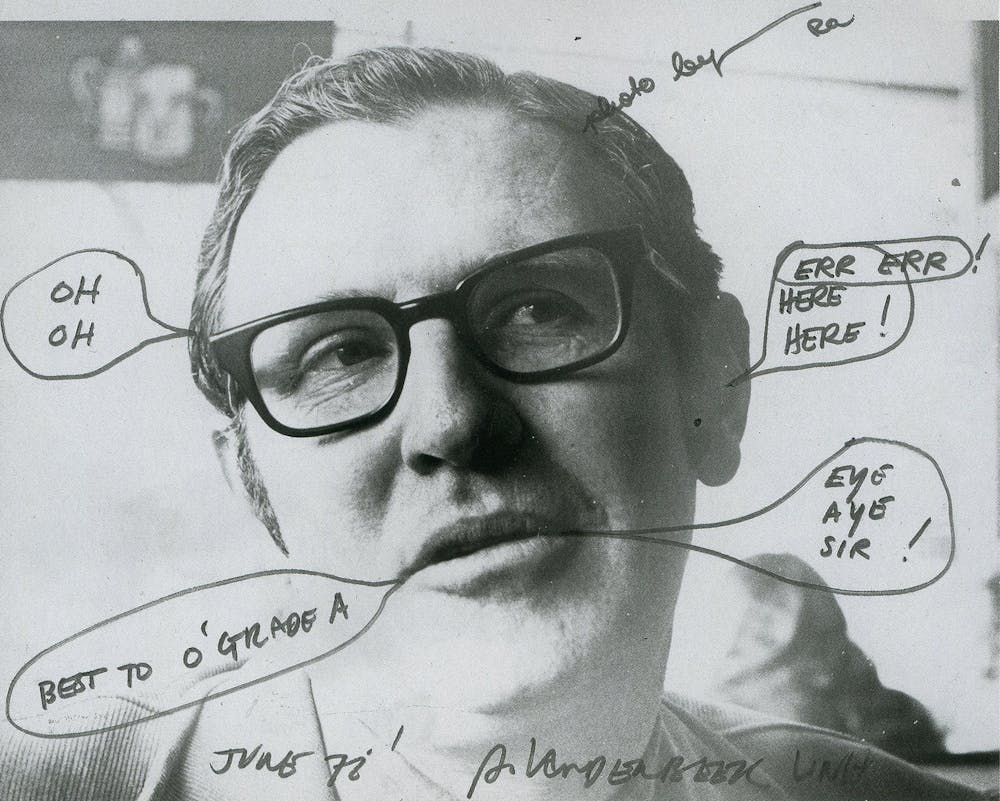

In 1972, Gerald O’Grady was offered a position that many academics spend their whole lives pursuing. As director of the Educational Communications Center at UB, O’Grady would be responsible for providing creative services to the University’s dozens of departments.

O’Grady told administrators he would accept the job — as long as UB created its own Center for Media Study and named him as its director.

Administrators took the deal, making UB home of one of the first media study programs in the country.

But before O’Grady crusaded for media studies, he was a medievalist.

A leaflet announces the 1984 spring workshops at Media Study/Buffalo. | Reprinted from Buffalo Heads: Media Study, Media Practice, Media Pioneers 1973-1990

As an undergraduate English major at Boston College in the early 1950s, he was struck by a 1942 dissertation on medieval poet Thomas Nashe. The dissertation was written by Marshall McLuhan, then a literary scholar at Cambridge University. O’Grady was so enamored by what he called McLuhan’s “linear and sequential and clear” writing that he picked up a copy of McLuhan’s first book, “The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of a Mechanical Man,” a dive into the mythology created by newspapers, magazines and advertising.

The study of these media was unheard of at the time, but McLuhan’s writing enchanted O’Grady.

McLuhan was the first to use “media” in 1967 to refer to the mass dissemination of information through television, newspapers and the like. To McLuhan, media became an extension of man’s senses now that a person could experience any place through the “push of a button.”

“Everywhere is now our own neighborhood,” he said in a 1960 television broadcast. “We know what it’s like to go on safari in Kenya, or to have an audience with the pope — to order a cognac in a Paris café. But not only is the world getting smaller — it’s becoming more available and more familiar, to our minds and to our emotions.”

As video left the studios and sets of Hollywood, and cameras shrank from the size of a car to the size of a briefcase. In 1965, Sony released the Portapak, the first commercially available portable video camera. McLuhan’s message began to resonate with a widening audience.

Video art emerged as a medium from the Portapak, with artists like Nam June Paik spearheading the belief that “in order to have a critical relationship with a televisual society, you must primarily participate televisually.”

Like the video art movement, improving access to what O’Grady called “mediacy” — the belief that one could not participate in society without understanding the channels or modes of communication — was at the heart of his mission.

Part of O’Grady’s vision was consolidating the three universes of media he experienced — the “pre-TV world, a TV broadcast world, and now, a post-TV world in which video art [was emerging]” — into one type of television that was public, artistic and educational at the same time, according to “Buffalo Heads: Media Study, Media Practice, Media Pioneers, 1973 - 1990.”

Between 1967 and 1969, O’Grady had already established and directed a media center in Houston where he taught film study to students in elementary, middle, high school and college.

O’Grady committed himself to traveling between Buffalo, Austin, Houston and New York City each week to teach seven courses at five different universities. For three years, he totaled a distance of 5,000 miles per week, all to answer one question: “How should media studies be defined?”

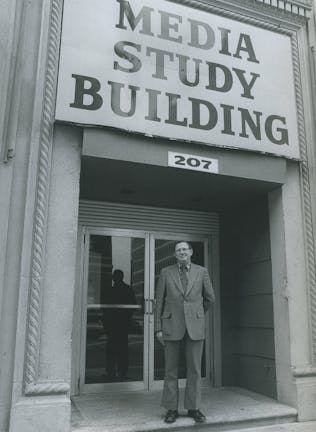

Gerald O'Grady at 207 Delaware Avenue, Buffalo, 1975. | Photo: Jane Hartney. Reprinted from Buffalo Heads: Media Study, Media Practice, Media Pioneers 1973-1990

When the U.S. government first instituted federal, state and local art agencies in the late 1960s, O’Grady took the opportunity to petition the IRS and New York State for a non-profit organization, Media Study/Buffalo.

Media Study/Buffalo rented the storefront of 3325 Bailey Ave. from a butcher, acquired 4.5-foot video cameras and employed a media artist to lead community workshops. It was the only local organization that made functioning media accessible.

The center became the film hub for Buffalo, as they screened works ranging from the silent to the experimental, from 1930s social documentaries to the French New Wave — basically anything you could imagine. Artists — including Jean Luc-Godard, Hollis Frampton and Sally Potter — visited the center to talk about their work, a rarity at the time.

In 1972, O’Grady founded the first media studies program to offer a degree in media art with a digital arts laboratory in the country. To him, media study was the study of the “interaction of culture and consciousness, focused on the codes of communication, including their technologies.” The center’s efforts were intertwined with Media Study/Buffalo and the Educational Communications Center for access to equipment.

Steina Vasulka teaching students at New York State Summer School of the Arts in 1983 | Reprinted from Buffalo Heads: Media Study, Media Practice, Media Pioneers 1973-1990

Noticing a condescension toward high school arts education among his academic colleagues, O’Grady established the New York State Summer School of the Arts within the center. High school students spent six weeks bouncing around the Ellicott Complex, learning about historical art movements and producing their own multimedia works under the guidance of visiting artists who shared their methods.

In intentionally constructing an accessible and enriching program, O’Grady recruited “outstanding creative artists in their own mediums” like Tony Conrad, Paul Sharits, Woody and Steina Vasulka and James Blue throughout the 1970s, according to “Buffalo Heads: Media Study, Media Practice, Media Pioneers, 1973 - 1990.”

“Someone like Tony or Paul if they were part of the community, so you weren't just seeing them in class,” said Sarah Elder, “You were sitting next to them at a screening, or you were part, especially with Tony, you were a member of a collective.”

Sarah Elder, an award-winning documentarian whose film pays attention to Indigenous communities, was hired by O’Grady in 1990, the year he retired.

“I was impressed with his mind. He was so fluent in so many areas and so willing to — he hadn’t heard of the kind of work I was doing because it was really experimental in those days,” Elder said. “And not in that when we say experimental, we sort of think of the certain American type, but it wasn’t like that. Jerry’s mind was bigger than that.”

Tenzin Wodhean is the senior arts editor and can be reached at tenzin.wodhean@ubspectrum.com