Nearly every inch of UB alum Michael Santoro’s bedroom is covered in World War I memorabilia: rare uniform pieces, medals, photos, letters, diaries and more.

But if his house were burning down and he could only save one thing, it might be his panoramic photo of “the lost battalion” — or perhaps the British uniform that was field issued to an American sergeant.

“I think I’d end up dying just sitting here trying to figure it out,” Santoro said.

Santoro — who graduated from UB with a bachelor’s degree in environmental design and architecture in 2021 and a master’s in architecture and historic preservation in 2023 — eats, sleeps and breathes World War I militaria.

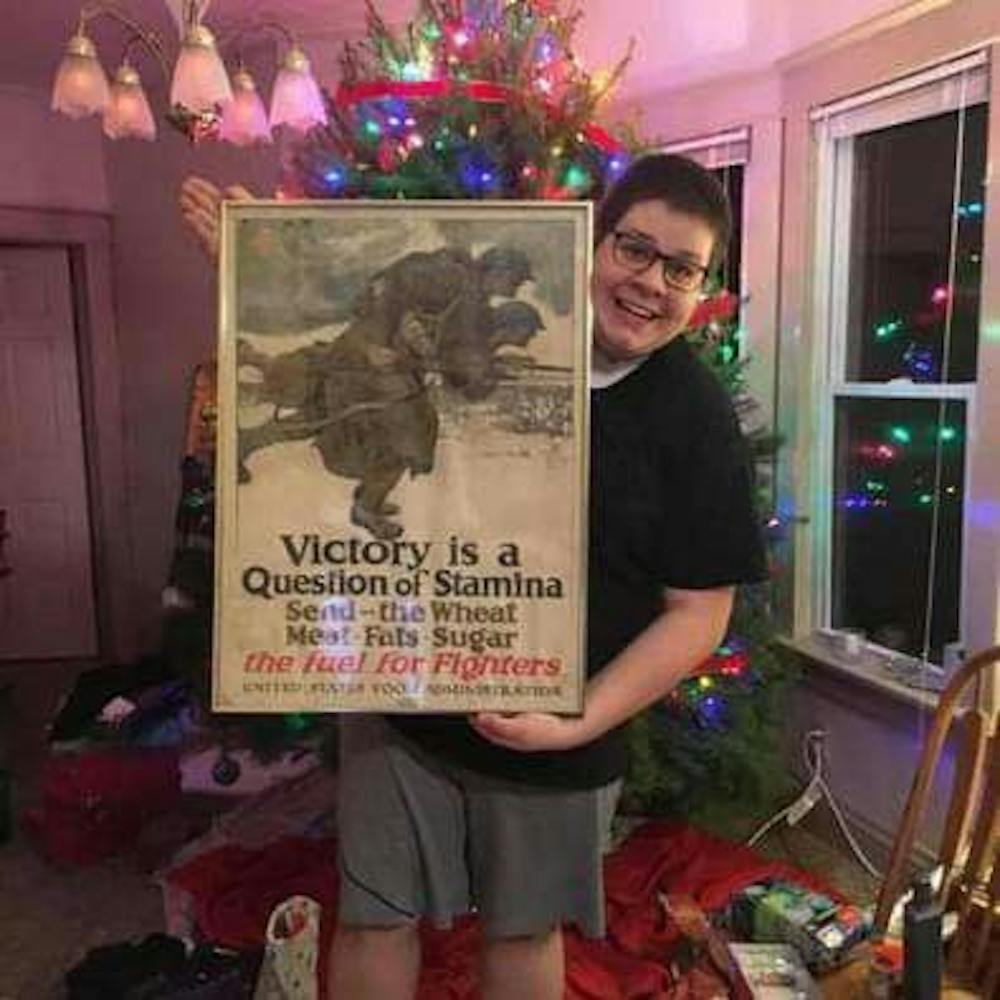

Santoro’s love of collecting began as a kid with a coin collection. Coins eventually turned into vinyls, and vinyls became World War I militaria on Christmas Day 2016 when he received a genuine propaganda poster.

The artifacts aren’t just objects to Santoro; they’re their own piece of history, with a deep story to tell.

One peculiar item that’s made its way into Santoro’s collection is a postcard from a World War I marine who’d hoped to be stationed in France and was instead dispatched to Haiti. He repeatedly tried escaping the American-occupied island. His attempts earned him 10 years in naval prison at Guantanamo Bay, where the postcard was mailed from.

That postcard is just one of many treasures that adorn the walls and shelves of Santoro’s bedroom. Santoro also loves the rich history contained in diaries because of the light they shed on their authors’ lives.

“Sometimes you really do get into the really deep s—t. I had this one diary from a guy in an ambulance company that dealt with guys that were wounded by gas,” Santoro said. “That really opened my eyes to the true horrors of chemical warfare during World War I because he goes into this horrific detail about what it would do to these soldiers.”

Discovering that rich history can also be a source of profit. After buying an item, Santoro frequently researches the soldier who once possessed it. A name and backstory can add value that triples the item’s original price, which he keeps track of in a massive spreadsheet.

“It was previously unnamed, and I’ve now put together this piece of history,” Santoro said. “I’ve given second life to someone whose family has probably forgotten about him.”

Santoro has turned his passion into professional opportunities too. This summer, he worked 14- to18-hour days and slept on a couch in the American War Museum outside of Gettysburg. The museum, which started in December 2021 and opens this year, is dedicated to the Civil War and World War I.

“That was the f—king life, man,” Santoro said. “I was living and breathing the s—t that I loved more than anything else in the world. It was like walking into a museum and all the glass is gone.”

The museum’s creator, Eric Hutchison, discovered Santoro when he stumbled upon his World War I-themed TikTok. Santoro’s expansive knowledge spoke for itself; Hutchison invited him to help build the museum.

“We were going to random farms in the most rural parts of PA [Pennsylvania] and asking if they had any old rusty tin that we could buy off them so we could hammer it to the sides of the walls in the museum and make it look like a World War I trench,” Santoro said. “I’ve probably never had a better job in my life.”

Outside of his gig as a museum builder, Santoro wears many other hats (and helmets), including auction house cataloguer. Auction houses send him thousands of images, then Santoro spends hours writing descriptions for each one. Santoro is also a survey worker at a historical preservation firm, a freelance military researcher and a freelance writer for military publications.

“I would say that my pursuit of so many different jobs is more or less to avoid taxes in every capacity,” said Santoro.

Santoro might not be afraid of the IRS, but there is one thing that keeps him up at night: the fear of mistakenly presenting false information.

“If I’m selling an item that belonged to this guy, I’ll go into such detail about his life and it’s so unnecessary,” Santoro said. “Like, ‘Arthur H. Kaufman was born on a stormy winter’s night on f—king December 24, 1894.’ I get so deep into the history of it because I’m so scared of putting out wrong information.”

Another fear: he often feels that dealers have to relinquish their morals in favor of profits.

“You have to focus on the stuff that you know is going to make you money,” Santoro said. “It’s choosing to focus on stuff that includes more macabre stuff, people love items that have death attached to it in some way.”

Santoro has his own moral code to maintain his integrity. For example, he refuses to buy anything Nazi-related, which he says makes up a substantial portion of many trade shows.

“I’ve actually become pretty famous in the community for s—t talking people at shows,” Santoro said. “I love being a young guy causing trouble for all these old assholes, and I’ve gotten into a couple of fistfights.”

Through shifting values and contentious company, Santoro turned his passion into a career.

“I found something that was my calling, when I started doing research and I found out that I could reawaken the memories of souls long forgotten in that way,” Santoro said.

Dominick Matarese is the senior features editor and can be reached at dominick.matarese@ubspectrum.com

Dominick Matarese is the Senior Features Editor at the Spectrum. He enjoys writing about interesting people, places, and things. In addition to running an independent blog, he has worked worked with the Owego Pennysaver, BROOME Magazine, the Fulcrum Newspaper, and Festisia. He is passionate about music journalism and can be found enjoying live music most weekends.