Content warning: This article contains sensitive information about suicide. If you are in crisis, please consider calling the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-800-273-8255 or dialing 988.

*

*

*

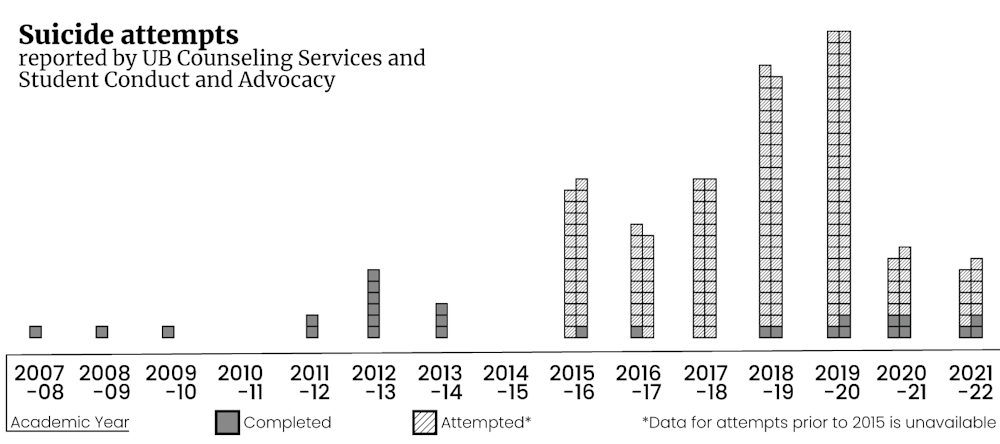

Twenty-eight UB students have died by suicide since the fall 2007 semester, with 10 of those deaths having occurred since the start of the 2019-20 academic year and three during the 2021-22 academic year, according to data from UB’s Office of Student Conduct and Advocacy.

The number of completed suicides among students has trended upward since the 2007-08 academic year, the earliest year for which data was available.

The rate of attempted suicides and reports of suicidal thoughts peaked in the 2019-20 academic year and have since decreased.

Of the 840 UB students who completed a needs assessment with Counseling Services between the start of the 2021-22 academic year and Jan. 21 of this year, 1.3% reported having attempted suicide within the past 12 months, and 10% reported having seriously considered suicide within the past 12 months. Both those figures represent reductions from their peaks during the 2019-20 academic year, when 3.1% of the 1,668 UB students surveyed said they had attempted suicide within the past 12 months and 17.1% reported seriously considering suicide.

UB appears to have rates similar to those of other universities across the nation. A representative survey conducted by the American College Health Association in 2019 found that 2% of college students nationwide had attempted suicide within the last 12 months, compared to 1.9% of UB students. The same survey found that UB students were somewhat less likely to report seriously considering suicide than their peers, 10.9% compared to 13.3%.

The suicide rate among those aged 15-24 has also increased since 2007, according to data from the National Center for Health Statistics.

Suicide was the second-leading cause of death in the U.S. among people between the ages of 10 and 34, according to data from the National Insitutes of Health.

The causes of any given suicide are complex and “come down to very individual needs,” but the pandemic and other stressful national events may have contributed to elevated rates of suicide and suicidal thoughts at UB in recent years, according to Director of Counseling Services Sharon Mitchell and professor of counseling, school and educational psychology Amy Reynolds.

“People were more isolated [and] maybe not able to access some of the support that they needed,” Mitchell said. “We’re in New York State, and we were hit hard at the very beginning [of the pandemic], and there’s a lot of grief and loss going on, which can cause people to feel hopeless. These are all just hypotheses, because without really knowing what was going on, it’s hard to say. But it’s been a hard couple of years, so it doesn’t surprise me that people were feeling more hopeless.”

Still, the upward trend of completed suicides among UB students is “highly concerning” and indicates that some students “feel completely hopeless and helpless,” Reynolds said.

“Despite the outstanding job being done by UB CS [Counseling Services], it seems like the institution needs to provide even more resources and support,” Reynolds said.

Counseling Services has increased the size of its staff by 20% in the past five years, bringing it to a total of 21 full-time counselors and three interns, Mitchell said. (The student population increased by 7% during the same five-year period.)

The department has also started an “embedded counselor program” to expand students’ access to counseling, which has so far placed counselors within the Medical School, Engineering School, Law School, Dental School and Athletics Department.

In addition to therapy, Counseling Services hosts or helps host events like international tea time, stress management programs in conjunction with Campus Living, QPR (question, persuade, refer) workshops and Suicide Prevention Week events aimed at reducing stress before clinical intervention becomes necessary.

Counseling Services “closely monitors demand for services,” which it uses to “advocate for additional resources,” Mitchell said.

Counseling Services isn’t the sole department on campus responsible for student mental health. For example, the Students of Concern Team, spearheaded by officials from Student Conduct and Advocacy, reaches out to and assesses students whom University Police officers, Campus Living officials or UB community members have identified as “students of concern.”

Elizabeth Lidano, director of Student Conduct and Advocacy, declined a request for an interview.

UPD, another key component of UB’s mental health response system, responds to mental health calls, takes students in crisis to Counseling Services and transfers students exhibiting “very disturbing warning signs” to Erie County Medical Center, according to Deputy Chief of Police Josh Sticht.

UPD is the only on-campus department authorized by state law to hold someone involuntarily. UPD transferred 33 individuals to Erie County Medical Center for an involuntary psychiatric evaluation in 2021.

Somewhere between 65 and 70% of UPD officers and all UPD dispatchers have received Crisis Intervention Team training, which is now required to complete basic police training, Sticht says. Officers with Crisis Intervention Team training are UPD’s “first choice” when responding to a mental health call, but officers without that training still have a “basic level” of crisis response training.

UPD also trains RAs and other Campus Living officials, who are often the first to respond to a student experiencing a mental health crisis, at the beginning of every academic year.

Brian Haggerty, senior associate director for Residential Life, didn’t respond to questions from The Spectrum in time for publication.

In addition to department-specific initiatives, Student Life has launched a communications campaign called “Taking Care,” which aims to educate students about on-campus “wellness-related resources” and is planning a wellness program for the 2022-23 academic year with the Student Association and Residence Hall Association, Vice President of Student Life Brian Hamluk said in an email to The Spectrum.

But some students, like Grace Verwerie, a junior legal studies major and president of UB’s Active Minds club, an organization focused on mental illness and mental health awareness, would like to see UB do more to address mental health.

Verweire commends UB for communicating with professors about creating less stressful classroom environments, transitioning back to in-person classes smoothly and providing “excellent” academic resources that work to reduce stress. But she says administrators need to engage with the conversation surrounding mental health, hire more counselors, increase the number of available counseling appointments, provide an on-call counselor and train 100% of UPD officers in CIT, among other reforms, to address students’ needs.

“One [suicide] is too much,” Verweire said. “It shouldn’t come to that at all. But as a university, we have the resources to explore these [new] options. We have the resources available to us to be trailblazers, to be on the front lines of this battle against mental illness.”

Students also hold long-standing concerns about Counseling Services’ 10-appointment limit on individual counseling sessions per academic year. Exceptions to that limit “have been made on a case by case basis,” and students can attend an unlimited number of group therapy sessions, Mitchell said.

“Students, faculty, and staff need to have greater awareness of the comprehensive programs and services offered not just by our office but by a variety of offices to help promote students’ self-care and mental health,” Mitchell said via email when asked how Counseling Services can improve.

Warning signs that someone may be considering suicide include wanting to die, feeling like a burden, strong feelings of guilt or shame, hopelessness, extreme sadness or anxiety, researching methods of death, withdrawing from friends, extreme mood swings, increased drug or alcohol consumption, taking dangerous risks and more, according to the National Institute of Health.

Men, veterans, Indigenous Americans, white Americans, LGBTQ+ individuals and people with disabilities have higher-than-average rates of suicide, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. At UB, international students may be at higher risk due to “unique adjustment issues,” Mitchell said.

Suicidal thoughts can be treated with coping skills, support, therapy or a combination of the above, according to the Mayo Clinic.

If you or someone you know is dealing with a mental health emergency or an after-hours concern, call University Police immediately at 716-645-2222. If you are stressed or in need of someone to talk to, contact UB’s Counseling Services at 716-645-2720 and Michael Hall at 716-829-5800. If you are in a crisis situation, contact Crisis Services of Western New York’s 24/7 hotline at 716-834-3131. Students can also text the Crisis Text Line by sending “GOT5” to 741-741.

Grant Ashley is a senior news/features editor and can be reached at grant.ashley@ubspectrum.com

Grant Ashley is the editor in chief of The Spectrum. He's also reported for NPR, WBFO, WIVB and The Buffalo News. He enjoys taking long bike rides, baking with his parents’ ingredients and recreating Bob Ross paintings in crayon. He can be found on the platform formerly known as Twitter at @Grantrashley.