On a cold day in early February, more than two dozen students filed into Davis Hall 101 for their “Super Bowl.”

The students — all of whom completed CSE 199, UB’s freshman computer science seminar, the previous semester — were divided into two- or three-person groups.

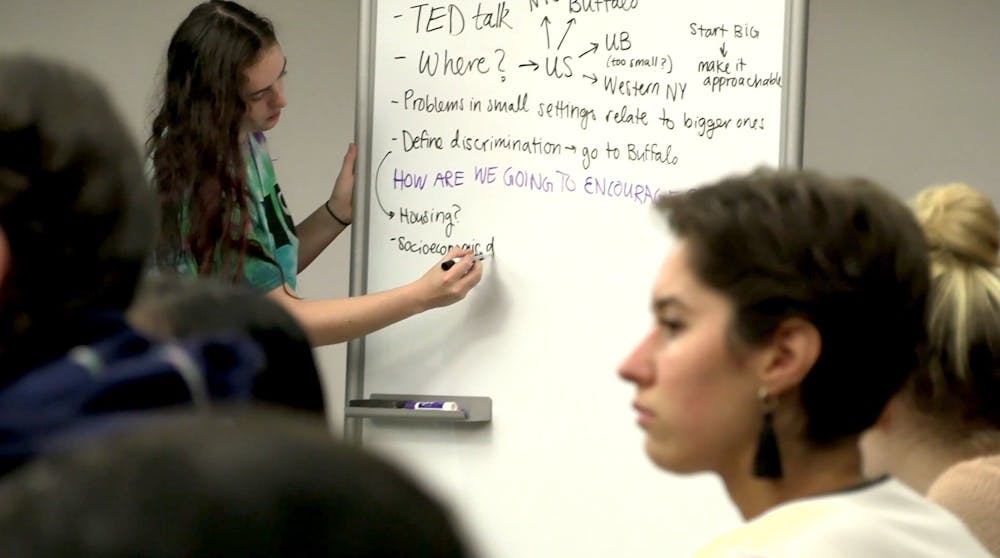

Then, each group took turns at the front of the room, where they presented their ideas to “Make Computing Anti-Racist.”

Students don’t often return to classes they have already completed, but that’s not the case for the protégés of Professor Dalia Muller.

Muller, a professor of Latin American and Caribbean history, has known she wanted to teach since she was in ninth grade. A self-described “historian by training and teacher by vocation,” Muller has a Ph.D. in history, and was the first woman, Black person or Latinx person to serve as Honors College director.

She is also the mastermind behind the “Impossible Project,” which she describes as a “transformative learning experience.” The idea behind the project is for students to collaborate with UB community members to solve seemingly impossible issues that Muller and other affiliated faculty present.

“The purpose of the “Impossible Project” is not to find a solution, but to find a new point of departure,” Muller told The Spectrum during a phone interview. “I do have students who come into the classroom and they freak out, they think, ‘What do you mean the impossible? How am I supposed to do the impossible?’ I want that cognitive dissonance, I want them to feel uncomfortable. I want them to come into a classroom that feels like it’s topsy-turvy and turned on its head because it provides a different form of an engagement with learning.”

As Muller describes it, the “Impossible Project” is an impossible task. Previous projects have been “Solve a Global Problem,” “Decolonizing the Brooklyn Museum” and, most recently, “Making Computing Anti-Racist.” Muller knows these problems will not be solved during the 15 weeks students have to come up with solutions, but she hopes her students will gain new perspectives on each issue’s significance.

In “Making Computing Anti-Racist,” students attempted to combat racist code and algorithms by doing everything from creating socially-responsible code certification to promoting prison reform.

The students in computer science professor Kenny Joseph’s freshman seminar course had less time than usual to complete their project. But Joseph says he believes his class still grew from the experience.

“I think [the project] definitely benefited the students,” Joseph said. “They saw content they otherwise might not have seen and stretch[ed] what they are comfortable doing in the classroom. It helped me change the way I understand how we should teach and, to an extent, what we should teach.”

Jeannine Nwade, a senior political science and business administration major, was involved in the most recent iteration of the “Impossible Project.”

Nwade served as a research assistant for the project the CSE 199 students eventually participated in. Despite not being a computer science major, Nwade says she gained a lot of insight on anti-racist coding.

“I was a part of the research team that researched the racialization of the internet and how it disproportionately affected marginalized communities,” Nwade said. “My work was used in the creation of the research module for computer science students. It was very eye-opening to understand how racial elements have been a part of the internet for so long (such as with the LAPD and NYPD’s use of predictive policing) and how it evolved over time (racial elements in speech recognition systems like Alexa and Siri).”

Muller stepped down as Honors College director in 2020 but says her inspiration for the “Impossible Project” stemmed from her previous position. As director, she says she wanted to create a transformative learning experience, create global citizens and make a curricular commitment to justice — something she hopes to continue in her faculty position.

“I came into the position [director of Honors College] with a really deep and radical commitment to diversity within Honors, which is a perennial problem across the nation,” Muller said. “[I also came] with a commitment to thinking about how we can use the space of the Honors College to really push at the boundaries of critical teaching and learning.”

Presidential Scholars, or recipients of UB’s Presidential Scholarship, served as the first generation of “Impossible Project” participants. Their scholarship is contingent on taking a one-credit, pass-fail course, HON 101 — a presidential scholar development seminar — that comes with admission into the Honors College.

Muller’s goal changed when she stepped down from her role as director. Initially, she had planned to implement the project into the Honors College’s curriculum but rather than expanding to honors students, Muller hopes the project will expand to each university department.

“When I stepped back into my faculty role I was thinking about how I should carry forward this project and I’m really excited with how it has evolved since then,” Muller said. “I’ve been working with a variety of different departments on building possible projects across the disciplines where I serve as a collaborator or facilitator in what is radical faculty to faculty collaboration. So, basically, I teamed up with faculty who are justice-oriented, no matter the discipline, and we figure out how to radically transform their classes.”

Julie Frey is a senior news/features editor and can be reached at julie.frey@ubspectrum.com

Julie Frey is a senior news/features editor at The Spectrum. She is a political science and environmental studies double major. She enjoys theorizing about Taylor Swift, the color yellow and reading books that make her cry. She can be found on Twitter @juliannefrey.