At her freshman orientation, Emily Fein heard a group of “white boys” using stereotypes to mock a fellow Asian student who was performing in a skit.

Fein, who was standing behind the boys, says she was unsettled and hurt by the casualness of the racist remarks. The pain continues to reverberate with her today.

The orientation took place before COVID-19 and before a spate of physical and economic abuse targeting Asians emerged across the U.S.

Now, such instances are hard to escape, appearing everywhere from Fein’s social media feed to the nightly news to the streets of New York City. On campus, Asian students say they feel there’s been an uptick in microaggressions, racial slurs and a general sense they are less welcome or don’t belong.

Fein, who identifies as Asian American, says she now often feels uncomfortable going about her daily life.

“I work at a grocery store, so it was one of the essential businesses that stayed open, and I was scared to work,” Fein, a sophomore political science and criminology major, said. “I [don’t] know what kind of harassment I’ll have to endure.”

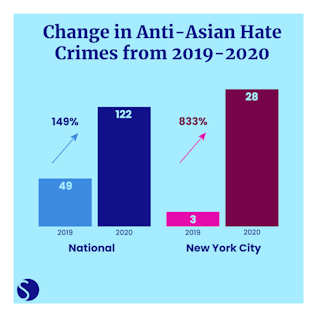

Hate crimes against Asians increased by nearly 150% nationally and by 833% in New York City in 2020.

Hate crimes against Asians increased by nearly 150% nationally and by 833% in New York City in 2020, according to a study by researchers at California State University. Since the onset of the pandemic, anti-Asian abuse — particularly toward East and Southeast Asians — has increased exponentially across the country. In mid-February, an Asian woman was assaulted and shoved to the ground in Flushing, Queens. That same week, an Asian man was stabbed in Chinatown. These attacks sparked widespread outrage on social media and instilled fear and anxiety in the Asian community. On Tuesday, eight people –– six of whom were Asian women — were shot and killed in three spas in Atlanta.

But racism toward the Asian community in the U.S. is nothing new.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the World War II Japanese internment camps and the revenge killings of South Asians and Middle Easterners after 9/11 have left many Asian Americans fearful for their safety.

Some students and professors say these issues often remain unspoken and the model minority myth — which is when individuals are compared to and criticized for not upholding “positive” stereotypes associated with their race — further erases their suffering. Asian students report feeling helpless and frustrated. As if the ongoing pandemic weren’t enough, they also have to deal with growing xenophobia and violence against members of their community.

Fanny Liang, a junior environmental design major, says she doesn’t have an avenue to navigate her emotions on this topic. She talks to her friends, but she says it doesn’t help ease her pain.

Liang says she “still [feels] helpless.” She tries not to bring any attention to herself and stays up to date on the news about hate crimes in her NYC neighborhood so she can caution her friends and family.

“I’m a little more careful when I’m in public, and I [try] to sound nicer if I need to say something,” she said. “I’ve told my family to be extra careful too. It’s sad that I have to tell them, but I want them to be safe.”

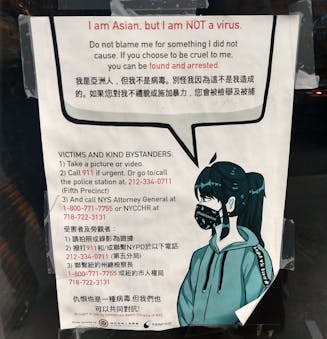

Anti-Asian attacks aren’t only physical. Many Asians have had to endure verbal abuse as well. This violence threatens the community’s mental wellbeing.

Eileen Ma, a senior communication major, says such incidents make her “sick to [her] stomach.” She says she avoids using social media because the posts about anti-Asian crimes make her anxious and add to her existing stress.

“I’m worried about my family members being the next victim,” Ma said.

Isok Kim, an associate professor of social work, says experiencing or even witnessing hate crimes and racist remarks increases “psychological and emotional uncertainty and vulnerability,” which can lead to mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression.

“When you are forced to constantly scan your surroundings, you are being forced to expend unnecessary physical and psychological energy that could otherwise be used to promote and restore your psychological and emotional well-being,” Kim said.

Anti-Asian attacks aren’t only physical. Many Asians have had to endure verbal abuse as well.

Kim says many Asian communities engage in collective mechanisms like social interactions and gatherings to cope with the abuse. But these strategies aren’t possible due to the pandemic.

He says by not being able to “to engage in and take advantage of cultural coping mechanisms, xenophobia and hate crimes are likely to further exacerbate [the] collective mental health of Asian communities well beyond the physical attacks and horrific death reported in the media.”

Many students and professors say they are worried that calling COVID-19 the “Chinese Virus” only exacerbates the problem by blaming Asians for the pandemic.

They say it’s only making the situation worse.

Liang says the Trump Administration’s nationalistic rhetoric has “emboldened” some people to be openly racist and act upon their anger.

“When Trump refused to stop calling COVID-19 a ‘China Virus’ and blamed the worldwide pandemic on them, he and the federal government essentially marked Asians living in the U.S. as a target of hate crimes,” Kim said.

Deputy Chief of University Police Joshua Sticht says there haven’t been any reported incidents of hate crimes against Asian students at UB during the 2020-21 academic year.

But, he said, an “unknown male” approached an international student from Korea last March “in a threatening manner with clenched fists,” and “even though he didn’t touch the victim, she was understandably upset by the incident.”

Even without physical violence, Asian students at UB say they face microaggressions and hear racially insensitive remarks on a regular basis.

Josie Morgan says she was in line to get food at the Atrium in March 2020 when she heard Campus Dining employees taunting a group of Asian students.

“Two of the workers behind the counter served a group of Asians and they said, ‘Look, it’s Corona’ as the girls were leaving,” Morgan, a junior music theatre major, said.

Members of the Asian community say the model minority myth is a tool that upholds racism toward Asians and pits minorities against each other. Members of this community say it minimizes their experiences as people of color in the U.S. and downplays their oppression.

Kim says the myth that all Asians are smart and innately successful and that other minorities should follow in their footsteps as a result was a “divide and conquer” strategy intended to pit Black and Latino Americans against Asians.

“Many Asian Americans bought into this myth, aligning with white, middle-class [people] and their narrative,” Kim said.

Nadine Shaanta Murshid, interim associate dean for diversity, equity and inclusion, and an associate professor of social work, says this hierarchy between races was created by colonization and imperial power structures to uphold white supremacy. She says the model minority myth “erases the racism and hardships” endured by Asians, and also puts forward harmful rhetoric that only immigrants who benefit the economy are welcome in the U.S.

She says apart from the model minority issue, racism against the Asian community is harder to recognize because they are not a monolith. She says not all Asians look or behave the same and the reasons behind their targeting for racial violence are different.

“Violence against Asian Americans or Asians has also received little attention because there’s no [single] manifestation of Asia, so it’s difficult to understand if it’s anti-Asian racism or just a regular crime,” Murshid said. “It’s not that straightforward and they’re all seen as unlinked events so it erases the violence that Asian Americans experience.”

Murshid says people shouldn’t get into issues of “oppression Olympics” but instead should come together to fight all instances of racism. She says racism against all communities is part of the same problem and stems from colonialism and white supremacy.

“Racism is something that affects all communities but in different ways,” Murshid said. “It’s not about who’s oppression counts and who’s doesn’t, it’s about power dynamics created by whiteness and white supremacy.”

Vindhya Burugupalli is the senior engagement editor and can be reached at vindhya.burugupalli@ubspectrum.com or on Twitter @vindhyab_ .

Vindhya Burugupalli is the engagement editor for The Spectrum. She loves traveling and documenting her experiences through mp4s and jpegs. In her free time, she can be found exploring cute coffee shops and food spots.