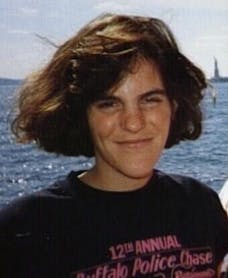

In the early afternoon of Sept. 29, 1990 — 30 years ago today — UB sophomore Linda Yalem went for a run along the Ellicott Creek Bike Path.

An avid runner, Yalem was training for the upcoming New York City Marathon. She loved the sport, and had joined The Spectrum only three weeks earlier with the intention of profiling marathon and cross country runners.

She never wrote the story.

Yalem was brutally raped and murdered on the bike path that afternoon.

She was 22.

On Sept. 29, 1990, Linda Yalem went for a run along the Ellicott Creek Bike Path. She was raped and murdered by Altemio Sanchez.

Her only story — about the thrills of cross-country running — came out posthumously, in the Oct. 3, 1990 Spectrum issue.

In the 30 years since her death, Yalem has been honored through memorial runs, safety patrols and a scholarship in her name. But the anniversary of her tragic passing begs a question: Is the bike path safer today than it was 30 years ago?

On the surface, the answer is obvious: yes. Yalem’s assailant — the serial killer Altemio Sanchez, who gained a national profile as the Bike Path Rapist — will spend the rest of his life behind bars. University and Amherst Police each have dedicated resources to protecting pedestrians. And it has been nearly 11 years since a violent crime has been reported on the trail.

Yet, some students, particularly women, are still wary.

They said the question isn’t whether or not the trail is safe; the statistics clearly indicate it is. Rather, they worried that something like what happened to Yalem could happen again and that neither the school nor the town is doing enough to protect them.

Orly Stein, a junior information technology and management major, said she was told about Yalem’s homicide in freshman year and that she’s felt uncomfortable being there ever since.

“I would never walk there alone at night,” Stein said. “I ran there once alone and after that I never went back because it was creepy.”

Katelyn Reilly, a junior chemical engineering major, said she was told when she came to UB that “someone was raped on the trail,” but that she never received any additional information and that she didn’t know if it was true.

“I wouldn’t call it a safe area, just because it’s pretty secluded in some parts and it’s not very crowded,” Reilly said. “I’ve only run on it during [the middle of the] day and most times I’ve been on it it’s been pretty empty.”

Reilly said she doesn’t listen to music and always runs with her phone.

Deaths like those of Mollie Tibbits, Vanessa Marcotte, Karina Vetrano, Alexandra Brueger and Wendy Karina Martinez got wide publicity in mainstream press and on social media and have helped stoke fear among women runners.

Last November, Runner’s World published a survey that showed that 84% of women have been harassed while jogging — and that 70% of men have not. The organization has published a toolkit to help female runners stay safe.

Deputy Chief of University Police Joshua Sticht said the UB trail is well-maintained, but he cautioned against students traveling it alone.

“Our advice for UB students using the bike path is to use the path with others,” Sticht said. “While the bike path has been very safe for the last several years, we don’t want anyone to take their personal safety for granted.”

‘Her death is painfully awakening’

Saturday, Sept. 29, 1990.

Linda Yalem awoke to a clear, 60 degree day. She got on her running pants and popped a cassette into her Walkman media player. Then, she left her Richmond quadrangle dorm room and crossed the street to begin a run on the bike path.

Yalem left the Ellicott Complex not long after noon.

By 9:30 p.m., when she still hadn’t returned, she was reported missing by a roommate.

At approximately 10:30 a.m. the following day, Amherst Police began searching the bike path. More than 25 officers searched three patches of woods. Yalem’s body was found in the third patch. She had been strangled and her clothes were pulled over her head.

The attack came as a shock to students, even though the Central Park jogger case was still on their minds from the previous year. Amherst had long been a safe, upper-middle-class town. It couldn’t happen here.

But it did. And as it turned out, it had happened twice before — in the span of 14 months.

The university did not warn students that two other women had also been attacked within a half-mile radius of where Yalem’s body had been found.

In an editorial published to The Spectrum on Oct. 1, 1990, students called the rape and homicide “shocking to us all.” They were particularly appalled by its “brutality, senselessness, and because it happened in the middle of the afternoon.” And it happened “so close to home.”

“Like a bucket of cold water smacking us in the face, her death is painfully awakening us to how close and terrible sexual assault is,” the editorial read.

“We have continually announced not to run alone, and we make every effort to discourage running alone,” Lee Griffin told The Spectrum in September 1990.

Students often walk around campus without fearing anything, as if they are unbreakable, the authors wrote. Yalem’s murder was so stunning because it challenged that notion — maybe students aren’t as indestructible as they think.

Over the following years, everyone expected the assailant to strike again. The FBI issued warnings cautioning that a suspect with that m.o. — modus operandi — could target another bike path in the Greater Buffalo area.

In response, UB administrators preached safe outdoor behaviors. The Phi Delta Theta fraternity distributed emergency whistles to students. And UB began the Linda Yalem Memorial Safety Run, which ran for 28 years, until it was discontinued in 2018.

Lee Griffin, the then-director of public safety at UB, was adamant about running with a friend on the bike path.

“We have continually announced not to run alone, and we make every effort to discourage running alone,” Griffin told The Spectrum in September 1990. “Unfortunately it takes a tragedy like this to register it in student’s heads.”

Amherst Police Chief John Askey stressed the same point.

“There is a danger to women who run the path alone, and the best possible protection is company,” Askey said in the same article. “This has taken important stature in our department since the first episode took place. We have worked with Public Safety, we have increased patrols out there and have special squads on the bike path, and we also have had officers on bicycles patrolling the path from morning to dark, as has Public Safety.”

In 2019, Runner’s World launched The Runners Alliance, an initiative to help make running safer for women. In a story, Lisa Haney provided four tips for runners looking to make their go-to running spots safer: knowing who to talk to, joining a trail organization, teaming up with cyclists and forming a run patrol.

Haney wrote that runners can advocate for “trimming overgrown areas or installing more lighting” — two areas where the Ellicott Creek Bike Path is seemingly lacking.

On Nov. 10, 1990, Bob McGuire, a co-worker of Altemio Sanchez, contacted Amherst Police to let them know that he had seen Sanchez on the bike path at least two times the previous 14 months and that he had found that to be suspicious.

Working on that tip, police set up surveillance at Sanchez’s home and brought him in for a voluntary interview. Sanchez was fingerprinted, but was only there for an hour and didn’t need to submit a DNA test.

Over the next 16 years, Sanchez committed an additional two rapes and two murders. He was also arrested twice on charges related to soliciting prostitution, but both times his charge was reduced to loitering and he paid a fine.

On Sept. 29, 2006 — 16 years to the day of Yalem’s homicide — Sanchez strangled Joan Diver, a 45-year-old mother of four, to death on the Clarence Bike Path (Diver’s husband, Steven Diver, is a chemistry professor at UB). Finally, a few months later, lab reports confirmed that Sanchez’s DNA matched that which was found on Diver’s car.

The Bike Path Rapist — who by now had also become known as the Bike Path Murderer — was finally behind bars.

‘Don’t take your personal safety for granted’

In the 30 years since Yalem’s homicide, officials have made a number of changes to the bike path.

Deputy Chief Sticht said that the biggest single change since Yalem’s passing was the “installation of emergency phones” that connect directly to Amherst 911 dispatchers.

Deputy Chief Sticht said that the biggest single change since Yalem’s passing was the “installation of emergency phones” that connect directly to Amherst 911 dispatchers.

These phones — encased in yellow frames with the word “emergency” spelled out — can be found approximately every mile along the trail. Sticht said the phones are “regularly” maintained and tested, even though he acknowledged that “most people use their cell phones to report emergencies these days.”

UB also has two blue-light phones along the path, which are located next to the Oozefest pits and the small gravel lot close to the cemetery on Frontier Road. These phones are a universal symbol of safety on college campuses and can be used to report suspicious activity or emergency situations.

During the warmer months of the year, officers from the Amherst and University Police departments patrol the trail, mostly on bikes. The bike patrol program was launched shortly after the Yalem homicide, according to Amherst Assistant Chief of Police Charles Cohen.

In Oct. 2012, UPD received a complaint of harassment/stalking on the trail. In Nov. 2000, a male jogger was punched and kicked by another male near South Lake Village. The suspect fled and the victim chose not prosecute the case, Sticht said. The victim suffered a minor laceration on his abdomen.

But since Jan. 1, 2019, UPD has received 59 total complaints on the bike path, nearly all of which concern premises checks, bicycle patrol or first aid. In that span, the Amherst Police have received 95 similar complaints. There hasn’t been a violent crime on the trail since 2000.

The bike path stretches more than a half-dozen miles, and much of it is secluded. It is a highly remote trail that is surrounded in many areas by high grass and tall trees. Parts of the trail run alongside a highway; others, a stream of water.

And at night, the path is completely deserted: no lights, very few pedestrians and an eerie silence. There are two blue-light phones on the short stretch of trail that runs through campus, but nothing on the rest of the trail.

Deputy Chief Sticht said that the park is “technically closed at night” but acknowledged that “people still do use it at night.”

“There have been talks about adding lights at the areas at the south end where it is actually part of an Amherst Town Park, but no talks that I am aware of to put lights on the whole path,” Sticht said.

Asst. Chief Cohen said he would “stay off the path at night, outside a compelling reason.”

Sticht recommends that students download the UB Guardian App, which allows them to text chat and make emergency calls to University Police, share their location in real-time with others and enable a safety timer.

“I’m not sure you can prevent pure evil, as rare as it is,” Cohen said. “[My] best advice is just be vigilant and lookout for each other.”

Justin Weiss is the senior features editor and can be reached at justin.weiss@ubspectrum.com.

Justin Weiss is The Spectrum's managing editor. In his free time, he can be found hiking, playing baseball or throwing things at his TV when his sports teams aren't winning. His words have appeared in Elite Sports New York and the Long Island Herald. He can be found on Twitter @Jwmlb1.