James O. Putnam helped found the university, but he also considered black people “inferior.”

He wasn’t alone in his thinking –– many prominent people of his time held similar prejudiced views.

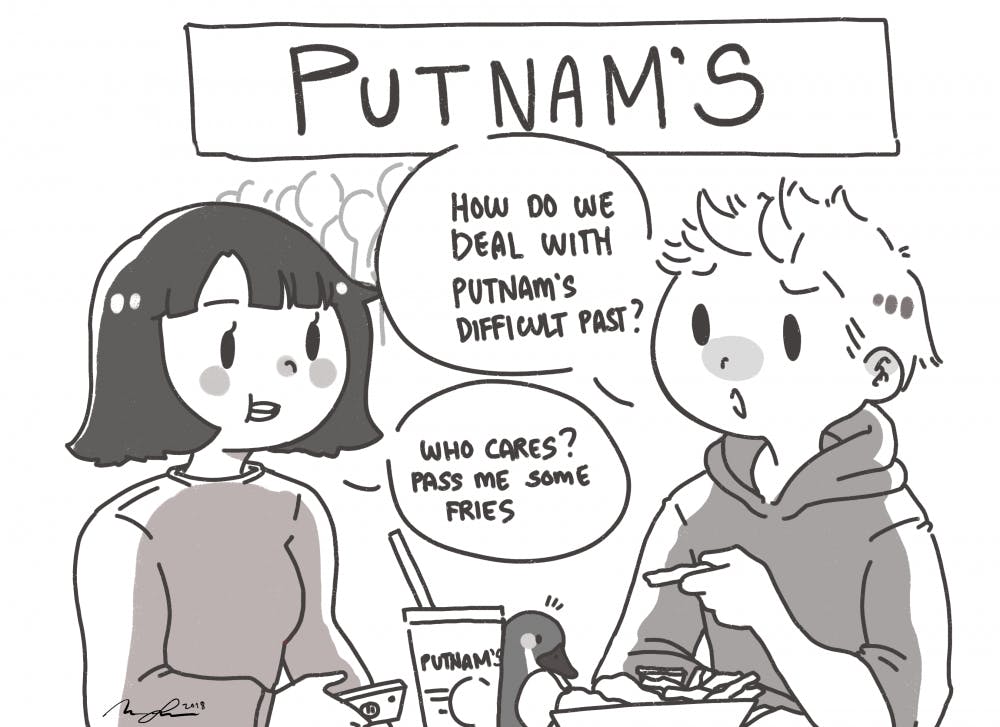

Still, Putnam’s is one of the most popular campus restaurants. More students probably know the name “Putnam” than know the names “Tripathi” or “Zukoski,” the UB president and provost or the name Kristina M. Johnson, the current SUNY chancellor.

Yet, until Thursday, when The Spectrum published an article about Putnam’s past, no students or administrators The Spectrum talked to knew about his problematic views.

We think that is wrong.

We are asking UB to recognize and talk about the problematic histories of the people it honors. We think students should be able to decide whose names are part of their everyday lives, gracing the spaces where they eat, sleep and study.

In May 2017, The Spectrum wrote about Millard Fillmore, UB’s founder and the nation’s 13th president. As president, Fillmore is largely forgettable. He never even won an election, but simply became president after Zachary Taylor died in office. His biggest legacy is the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which made it a crime for northerners not to return runaway slaves.

Yet, at UB, multiple buildings carry his name.

UB claims we celebrate these figures for their contributions to the university, not their politics or opinions.

We understand. But as an academic institution, UB should be forthright about that evolution and post plaques on buildings explaining the past of those whose names they carry. Students taking tours, living in dorms and studying in libraries should know the history behind these names.

The university has events like DIFCON –– a panel-led discussion about topics like race relations –– which touch on complex national issues, but faculty, staff and students may not always be able to attend them.

The Spectrum also learned that not every historically-complex figure whose name appears on a UB building has a lauded university story.

Peter B. Porter was a War of 1812 hero and former U.S. Secretary of War. He had no connection to UB, in fact, he died in 1844, two years before the university was founded.

Porter was a slave-catcher and owned five to six “indentured apprentices” who were former slaves in the south. He referred to free black Americans as “the most licentious, turbulent and worthless part of our population.”

Yet he has an Ellicott Complex residence hall in his name.

We understand UB’s current administrators can’t be responsible for names used in the past. But the university is responsible for knowing about the past, educating us about it and for deciding on names that suit the present and future. We found out the information about Porter after a ten-minute Google search.

Google was not around in 1974 when UB completed the Ellicott Complex, but information on Porter’s slave-catching past is available at the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society Library.

We are asking our administrators, historians, faculty and librarians to educate us about the names of the places that define our academic experience.

The Spectrum thinks all buildings named in the 1800s should be discussed. We also think UB should consider looking into the name of Kapoor Hall, home of the pharmacy program and built in 2012. Last year, John N. Kapoor, a 1972 graduate, was indicted for heading a nationwide conspiracy to bribe doctors and pharmacists to widely prescribe an opioid cancer pain drug for people who didn't need it.

UB spokesperson Cory Nealon said UB has formed a “naming committee” for buildings and landscapes on campus. The committee is in the process of developing policies and plans for the naming of old and new structures and places, Nealon said.

We are thrilled with this news, but we also want to make sure these decisions and findings are open to all.

Students deserve the right to know the history behind the names on walls where we sleep, eat, study and imagine our futures.

The editorial board can be reached at opinion@ubspectrum.com.