UB administrators presented data on Ph.D. stipend packages during Tuesday’s Faculty Senate meeting, reinforcing the university’s stance that they are fair and competitive compared to other institutions.

Provost Charles Zukoski, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Robin Schulze and Dean of the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences Liesl Folks presented data about how their schools determine Ph.D. stipend packages.

The presentations were a response to English Ph.D. student Nicole Lowman’s presentation during an October Faculty Senate meeting. Zukoski said there was not enough time to discuss Lowman’s analysis of the stipends at the last meeting, so he wanted to clarify the university’s data and debunk “unverified” information that circulated across UB’s campuses.

The debate over whether Ph.D. student, graduate assistant and teaching assistant stipends are high enough has drudged on for nearly a year-and-a-half. Through the Living Stipend Movement, students, faculty and staff have publicly voiced their concerns through sit-ins, rallies and protests on campus.

Students argue that the rising cost of living in Buffalo, $24,072, means students need a higher stipend and that UB should take money from the UB Foundation or administrators’ salaries to increase stipends.

But the general consensus among administrators remains that the university provides graduate students with a competitive stipend package –– on average about $18,000 a year –– above the national average.

That puts the average graduate student’s stipend just below the $18,408 average of the 24 institutions that provided data to the Association of American Universities for 2017-18.

Zukoski, Folks and Schulze all said that they feel the stipends UB provides are fair –– especially during a time when students are expected to experience some fiscal hardship –– and said that there are no “hidden pots of money” that some critics have claimed exist.

Schulze said the College of Arts and Sciences distributes roughly $10 million in stipend packages throughout its 29 departments.

Schulze said within the CAS, there are several Ph.D. disciplines that universities across the nation are “over producing.” She said there are a lot of people out of jobs with certain Ph.D.s and that it makes sense to admit fewer graduates to raise stipends and increase the quality of incoming students in order to better the outcomes for students.

“Departments are free to use their funds however they see fit to support graduate students,” Schulze said. “It’s their money, they can use it in whatever way they desire. So departments are free to shrink the size of their graduate cohorts and raise their stipends. And I actually encouraged several departments in the college to do just that.”

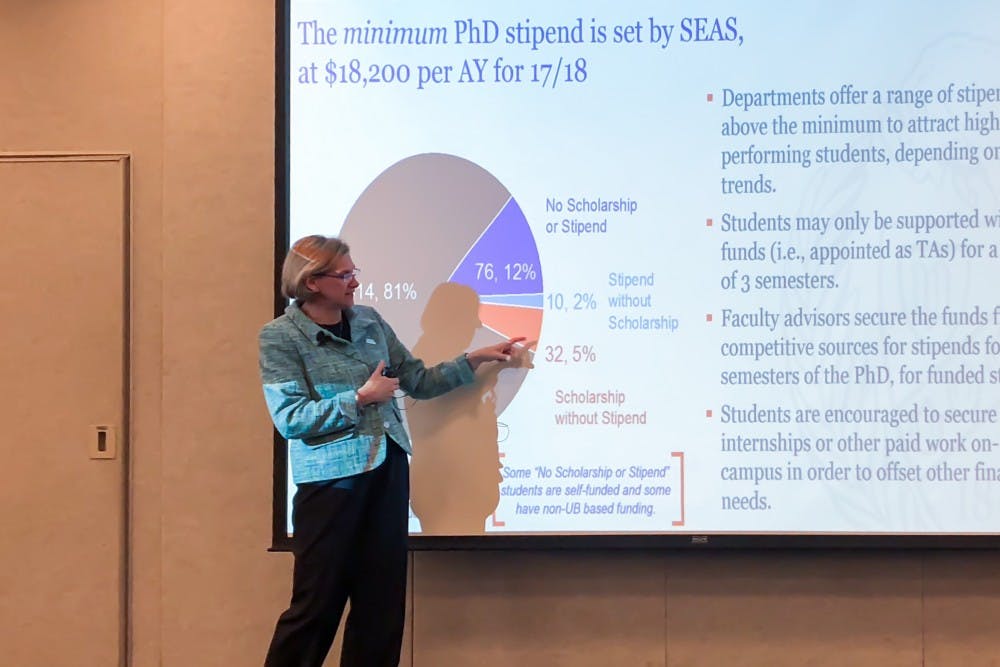

Folks said in order to attract a competitive cohort, UB provides engineering graduate students with a maximum $30,000 full-stipend package to remain competitive with other institutions. But, Ph.D. students are only provided with this “central funding” for a maximum of three semesters. Subsequent semesters are paid for by grant money that faculty bring into the department, Folks said.

Folks put the responsibility on the school’s faculty to secure funding for its Ph.D. students. She added that if students need more money to meet the standard of living in Buffalo, they should look for additional jobs to meet their fiscal needs.

“Our Ph.D. students are actively encouraged and supported to secure paid internships or other paid work on or off campus if they have other fiscal needs,” Folks said. “We work hard to make sure that when students have fiscal needs that are not met through [their stipend], we can support them by making sure they know how to get access to information about where there are paid jobs available.”

English professor Jim Holstun, a vocal supporter of the Living Stipend Movement, said the graduate school’s financial aid website explicitly tells students not to work extra jobs unless they have an “unusual economic necessity.”

“We are putting our students in contradiction to what we say the living stipend should pay,” Holstun said. “Our students are in danger. They are crashing. Our programs are crashing. We need to address this and we need to provide to our students basic living subsistence, if we don’t, we’re not doing our job.”

Graduate students at the meeting said they barely have enough time to teach and work on their dissertation and were frustrated at the dean’s suggestion to tack more work onto their schedule.

During a Q&A following the presentations, graduate students and supporters of the Living Stipend Movement voiced their concerns about the university’s reluctance to increase stipends.

English Ph.D. student Ariana Nash said the financial data the administrators presented was misleading. She said graduate students pay over $2,000 in mandatory fees and felt the numbers should’ve reflected the amount received after fees are subtracted.

She was also frustrated that none of the presentations mentioned the cost of living in Buffalo. If the average stipend is subtracted from the average cost of living, there’s roughly a $6,000 gap between what students earn and what is needed to live above the poverty line.

Nash asked Zukoski and Schulze why graduate students are still not earning the amount of money they should be in order to focus their time on school, not working extra jobs.

“Why are we not talking about what the administration can do to give departments more money for [Ph.D.] students?” Nash said. “Because that’s the issue. It’s not a local issue, this is an across the board university-wide issue that graduate students are not making enough to live on and no part of what [the deans presented] was addressing the question of where the university is putting its money and why it's not investing in its graduate students.”

Max Kalnitz is the senior news editor and can be reached at max.kalnitz@ubspectrum.com