Kara Rodriguez* doesn’t feel smart enough to study for big exams without Adderall.

Erika Hussein’s* tight-knit family is strict about grades. She’s afraid to disappoint them and calls Adderall a “necessary evil.”

Alexa Smalls* mixes Adderall with caffeine pills she buys on Amazon for an extra boost while studying.

Candy-colored pills, often dubbed “addy,” fill the pockets of UB students and offer them the most elusive 21st-century promise – the ability to do it all.

Students who take Adderall say it allows them to focus on tests and still have energy to hit the gym and party over the weekend. The effect starts about 20 minutes after a pill is popped and the peak occurs about an hour and a half in.

A thriving UB black market makes sure the pills are always within reach. Illicit sales are funding many students’ studies and extracurricular activities.

Adderall, the brand name for a mixture of amphetamine salts, isn’t difficult to get. Students huddle up in bathrooms, fraternity houses and even public places like the libraries, exchanging pills for money.

Rodriguez keeps her pills in an aspirin bottle so people don’t know what she’s really taking.

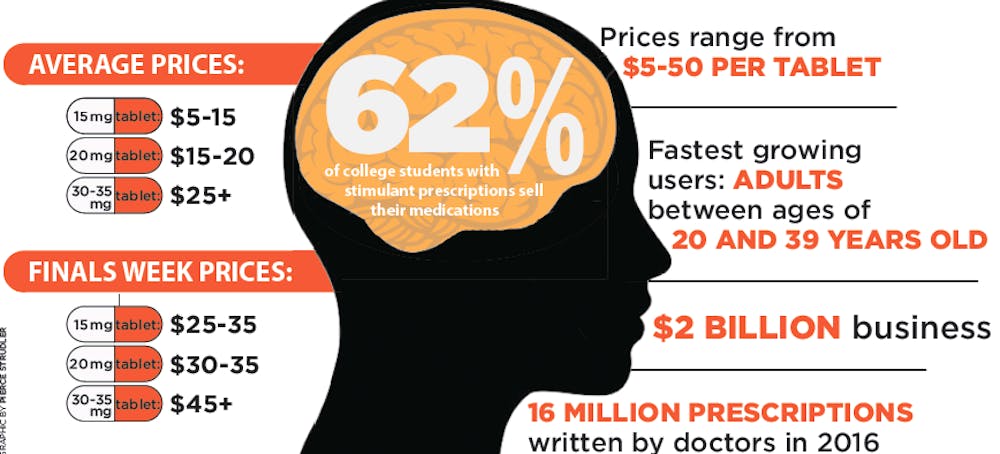

Adderall is a stimulant prescribed to treat Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, a neurobehavioral condition usually found in children and characterized by inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity. Prescriptions for the behavior have skyrocketed in the past 20 years and in 2016, doctors wrote 16 million prescriptions.

When Rodriguez takes Adderall, her heart beats faster the minute she realizes she’s on it. She feels separated from the world. Everything outside her is on mute. All she can hear is what’s going on in her head. It’s like her brain becomes a narrow tunnel. She can sit still for hours, focused on one paper or topic.

Adderall makes her want to study.

“When I take Adderall, I get that extra boost,” Rodriguez, a junior industrial engineering major, said. “I feel like I’m on a massive high. It’s a little step below marijuana and my brain just feels super heavy like a bolder is pressing up against it but at the same time, I focus on one thing and I don’t wanna move,” Rodriguez said.

Adderall gives her confidence and helps her maintain her GPA. She knows she has to be careful and she’s heard about people who get addicted. But in engineering, grades matter, she said, and tests are the sole measure of success in a class, so there is huge pressure to perform.

Without Adderall, she says, she’d be out.

That’s why she’s willing to pay anywhere from $20 to $50 per pill. She’s confident she can control her use and believes as long as she doesn’t take the pills regularly, she won’t get addicted.

The fastest growing group of Adderall users in the U.S. is adults between the ages of 20 and 39, according to Quintiles IMS, a technology company that gathers health data. Sales are also huge; in the U.S. Adderall is a more than $2 billion business.

Full-time students are the most likely abusers of the drug, according to a National Survey on Drug Use and Health report.

For UB students, it’s the study drug of choice. It’s easy to get, works almost immediately and is seemingly undetectable. And because it’s prescribed, it has a veneer of legality.

Students who have not used it themselves know of students who have tried it. Every student interviewed knew how to get it. Yet, Adderall use is still not discussed much by UB administrators or health professionals.

Students are rarely getting caught using it illegally. In fact, University Police only found four students this year and three students last year using the drug without a prescription, said UPD Deputy Chief of Police Josh Sticht. Police didn’t make any arrests in these cases because of the Good Samaritan policy, which prevents students from being arrested when people call police for help.

Sticht said UPD tries to pursue criminal charges against students who sell drugs rather than students who take them. But police haven’t arrested any students for selling Adderall yet.

Elizabeth Lidano, director of Judicial Affairs and Student Advocacy, hasn’t seen many cases of illegal Adderall use or sales either.

“It’s not super prevalent, or in large quantities,” Lidano said. “We might see it once in awhile, but I can’t say we’re overwhelmed with students being found with Adderall.”

Student Health Services prescribed Adderall to 32 students between Aug. 1, 2015 and July 31, 2016, according to Brian Hines, Records Access Officer.

Student Health Services has never treated any students for an Adderall overdose.

Jaclyn Singer, Alcohol and Other Drug Harm Reduction Specialist for Health and Wellness, said the university does not offer any seminars or meetings about Adderall use.

The National College Health Assessment sends out a survey every three years to college students nationwide – including at UB – and Adderall use doesn’t rank as one of the substances students say they use. Every incoming UB student must also complete the Alcohol.edu assessment, which asks students the same question. Adderall still doesn’t rank.

Alcohol and marijuana are the two most abused drugs so the university prioritizes them.

But 34 percent of college students use ADHD stimulants like Adderall non-medically, a 2008 National Center for Biotechnology Information study found.

And for many students in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) fields, Adderall is as necessary as a scientific calculator.

“STEM students need Adderall more than English majors do,” Smalls said. “STEM is something you really have to build on and it's just the foundation for what’s going to happen next. You really need to study and if you’re a person who parties every weekend it’s not going work, but if you do party every weekend you need a background to study, that’s why I would say that Adderall is a great backup.”

Adderall dealing

Former UB student Griffin Wells * used to sell Adderall.

He got a prescription from his doctor, although he does not have ADHD. He got the prescription to sell the drugs to UB students. He did not need to pass a medical or psychological test to get the prescription.

“I literally just said to my doctor that my friend gave me one of his Adderall pills and it really helped me and he put me on a low dosage of Adderall,” he said.

Students like Wells are making hundreds of dollars a month selling Adderall.

They are not big dealers, though. They are limited by their prescription, which usually gives them between 30 and 90 pills within a one to three month period.

Nationally, 62 percent of college students with stimulant prescriptions reported having sold their medication at least once, according to the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

No one at UB – not University Police, Judicial Affairs or Student Health Services – knows how many students are selling Adderall illegally because no one is talking about it or admitting it openly.

Student Health Services doesn’t know how many UB students have legal prescriptions because students aren’t required to list their conditions or medications. Student Health Services also has no records about how many students are addicted to prescription drugs or have to leave UB due to prescription drug addiction.

Caitlin Smythe*, a former UB student, underwent a more rigorous screening process before she got an Adderall prescription.

Smythe was 14 years old when doctors told her she had the short-term memory of a first grader.

She underwent two weeks of testing before doctors diagnosed her with ADHD. She had seconds to look at a picture and had to recite as many details as she could remember. She had to memorize dots and lines and tell her psychiatrist a story based on them.

She was diagnosed with ADHD at age 15 and her doctor prescribed Concerta, a drug similar to Adderall, and eventually switched to Adderall.

When Smythe came to UB, she was taking Adderall, but no one ever asked her about it or asked her to indicate she had ADHD.

She began selling during her sophomore year. She did it for the money, but also because the drug had stopped working for her and started working against her by causing extreme weight loss and anxiety-based shaking episodes.

Larry Hawk, a psychology professor at UB, said stimulants like Concerta and Adderall amp people up and if they are “pretty anxious people,” the drug might exacerbate the anxiety.

Once students found out Smythe had Adderall and wasn’t taking it they started offering cash.

“I would only really say yes to my friends and half the time, I wasn’t even charging for it, and then they would tell people and more people kept asking,” she said.

When finals week approached, she began to charge more and even began charging her friends.

“The less I knew the person, the more I would charge them,” she said.

Adderall dealers tend to spike up their prices during finals week.

“I remember for finals week two years ago I had to buy two 20 mg pills which would usually cost about $20 and it was more than $50,” Rodriguez said. “And last year I wasn’t prepared for finals week and I was panicking. I needed [Adderall] and I was asking everyone I knew who could’ve had a connection to someone that might sell it. Every single dealer was dry.”

A tricky diagnosis

Some students get tired of searching for a seller and decide to get their own prescriptions. Mimicking the symptoms is easy. Doctors know this but are often stuck.

“ADHD is a funny diagnosis,” said Richard Almon, adjunct pharmacy and biology professor. “There’s no way to objectively define it. It’s not like I can go in and take your blood pressure or look at this or look at that and I have an objective measure,”

If students are having trouble paying attention, they can ask a doctor to prescribe them the drug since there is no objective criteria for diagnosing, Almon said.

“Thought Catalog” published an article in March 2014 entitled, “How To Get Your Doctor To Prescribe You Adderall In 5 Easy Steps,” which outlined how people could fake symptoms to receive the drug.

It’s a lot easier to diagnose ADHD in children than adults, according to Hawk.

“ADHD is commonly diagnosed in the first few years of elementary school because the child makes the transition to the school environment and is struggling,” Hawk said.

But using Adderall as a study drug isn’t exactly a new fad, Almon says.

“Years and years ago in the ’60s when I worked in the steel mills, you could make a lot of money and get all the overtime you could handle,” Almon said. “This has been going on for years and years but maybe it’s become more popular, probably because it’s more available.”

Almon said Benzamine was the “fad drug” at the time that helped the workers to focus. He said people would line up waiting to be prescribed to sell it to other workers.

Dangers of the drug

Prolonged Adderall use has a number of health risks, which include heart attacks, strokes and reduction of hunger, according to Almon.

It can also be a gateway drug and addicted students begin to crave the clarity and super-human stamina the drug offers.

Rodriguez continues to take Adderall despite knowing the risks and feeling like she’s cheating herself by taking it.

Anita Sharma, a senior health and human services major, feels Adderall only gives students “temporary knowledge.” Instead of retaining information, she says Adderall encourages students to memorize.

She believes Adderall is a “disgrace” to the education system.

“Taking Adderall to study is like drinking liquor to socialize. How long can you keep taking Adderall without getting addicted to it? In medical school are you going to take Adderall before operating on a patient? When you’re an engineer and you’re operating on machines are you going to be high on Adderall? If students need to rely on a drug to make them smarter, they need to take a look in the mirror and ask themselves whether they’re in the right academic field to begin with,” Sharma said.

Hawk said it’s important for students to not become dependent on taking Adderall as a means for studying.

“People are increasingly recognizing that stimulants for ADHD don’t in the long run cure the problem; they mask the problem,” Hawk said. “And Band-Aids can be very useful, but a young adult should say to themselves ‘[each time] I use a Band-Aid how could I better prepare myself?’”

* Editor’s note: Names of students have been changed to protect their privacy

Ashley Inkumsah is the co-senior news editor and can be reached at ashley.inkumsah@ubspectrum.com.