Director: Simon Curtis

Screenplay: Alexi Kaye Campbell

Studio: BBC Films; Origin Pictures

Grade: A-

From the trailer, The Woman in Gold might seem as predictable and repetitive as any other movie in theaters. But this movie is a lesson as to why we sit through films instead of just judging them on a two-minute snippet: the characters come to life on screen in a way that flips whatever pre-conceived notions the trailer may have instilled in the viewer.

The film centers on a strong-willed old woman and a young investigative man struggling to overcome the oppressive judicial system that wronged the old woman and restore justice at all costs.

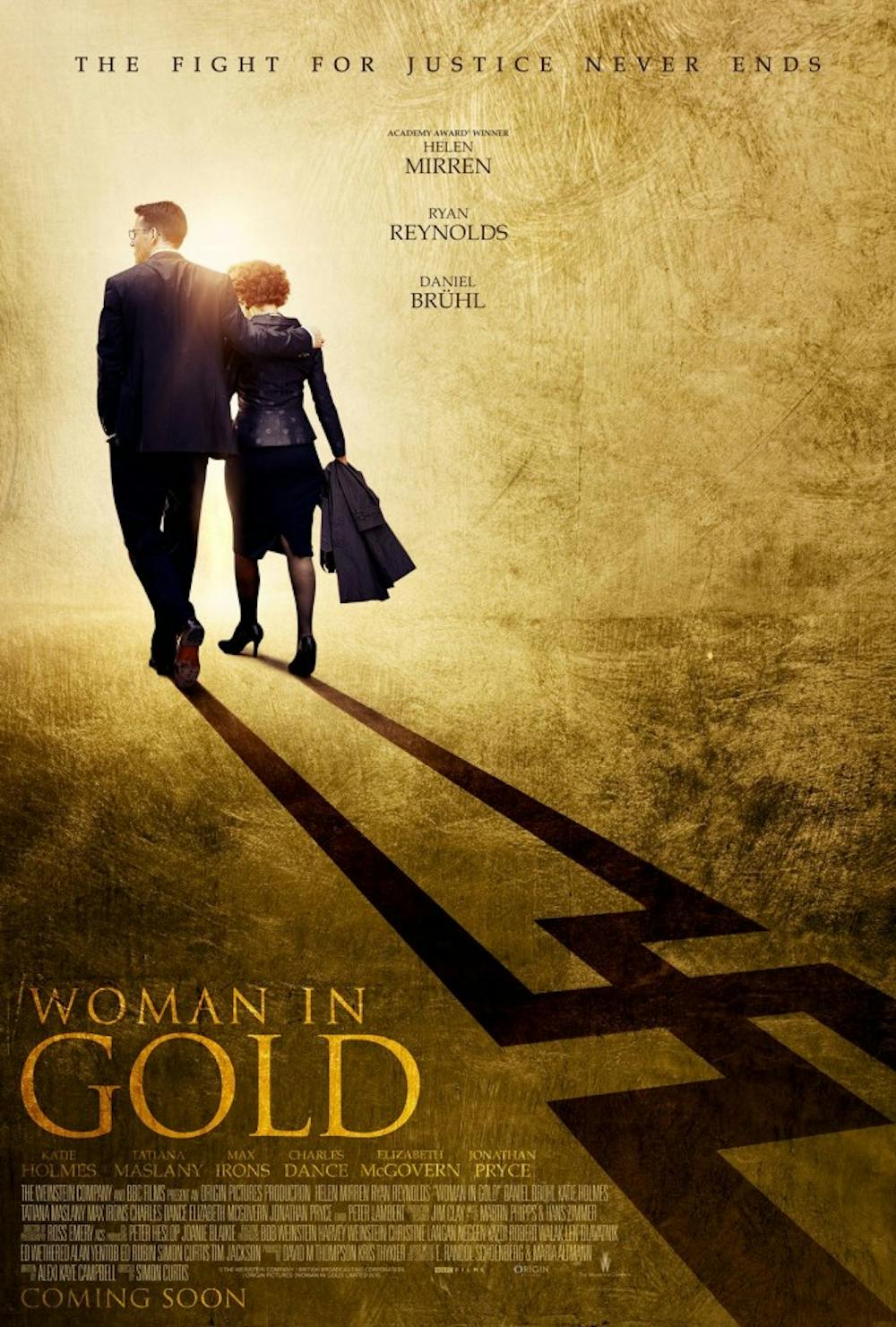

It stars Ryan Reynolds (The Voices) as Randol Schoenberg, a young lawyer in the midst of swallowing his pride and accepting a job at a new law firm instead of trying to get a job at a big firm.

His first assignment is to help Maria Altmann (Helen Mirren, State of Play) in an art restitution project – to help reclaim an Austrian painting known as “The Woman in Gold.” The painting belonged to her family and was confiscated by the Nazis but was never rightfully returned.

Ironically enough, this painting became, as one character put it, “the Mona Lisa of Austria.”

The movie seemed to be in such a rush to get to its plot that it totally skipped over several basic screenwriting points of character development. Though these fundamentals are missing, the film makes up for it with emotionally developed characters.

Screenwriter Alexi Kaye Campbell (Bracken Moor) knew everything couldn’t get into the film – but handing the creative control to only two-time director Simon Curtis (My Weekend with Marilyn) must have been no small feat.

For many films, the lack of plot cohesiveness would be problematic but in The Woman in Gold, the scattered plot highlights the depth of the character development. It is a reminder of how important the character aspect of storytelling is when pitted against plot.

Campbell’s screenplay is truly something to behold, as he never loses grasp of each character’s humanity. Every character has moments of wit and humor, sorrow and loss.

Throughout the film, Altman’s past is interwoven with the present-day story in flashback form. These flashbacks are so well done they make you want to abandon the primary story and get a whole other World War II film out of it. There is no sugarcoating of Nazi-occupied Austria and it truly is a breath of fresh air.

Mirren’s character embodies the spirit of being torn by memories of the past and how memories affect events taking place in the present; this highlights the theme of past versus present.

In the movie, there are moments when Altmann is ready to give up, but she moves forward with the proceedings, not because it is right, but because her past dictates her present.

Altmann seems to immerse herself in these moments, realizing in the wake of every event she faces, past and present are one and the same: she is never able to give up her quest.

The film’s ending was predictable – the result of the trial, in which the fate of the painting is determined, has a storybook result. Beyond the trial, however, the director chose to give the characters a more satisfying conclusion than the plot itself.

In an overall quite-predictable movie, the ending is so touching and beautiful it makes you want to spend more time with both Altmann and Schoenberg.

The movie has many shortcomings, but they should not overshadow the true talent and care that went into the screenwriting process and was brought to life on the big screen.

Both Simon Curtis and Alexi Kaye Campbell will find success in Hollywood because they understand the characters that are being portrayed.

The Woman in Gold does not have all the elements of good storytelling, but it manages to balance one of the more difficult tasks – character development.

Reuben Wolf is a contributing writer and can be reached at arts@ubspectrum.com