Kari Winter has dealt with men and teenage boys who exposed themselves to her while walking down the street. She’s far from alone.

More than 60 percent of 2,000 women surveyed reported experiencing street harassment, according to non-profit group Stop Street Harassment.

Winter, a professor of transnational studies, said women in big cities have similar experiences to the one shown in a viral catcalling video that has been filling Facebook feeds since late October.

The video, which has more than 30 million views on YouTube, showed actress Shoshana Roberts enduring 108 catcalls in the span of 10 hours while walking through the streets of New York City.

The video has created mixed reactions from the public, including UB students. Students question catcalling’s broad effect on society, as well as what some viewed a flawed perception of race within the video and how it was edited.

Rob Bliss of Rob Bliss Creative partnered with Roberts and Hollaback!, a non-profit movement launched by activists to end street harassment, to create the video titled “10 Hours of Walking in NYC as a Woman.”

BSU held a meeting Monday to discuss the video as well.

“The catcalling video made catcalling real,” said Noelle Nesbitt, president of Black Student Union (BSU) and a senior biomedical engineering major. “When I say this I mean, having a visual representation of something makes it undeniable.”

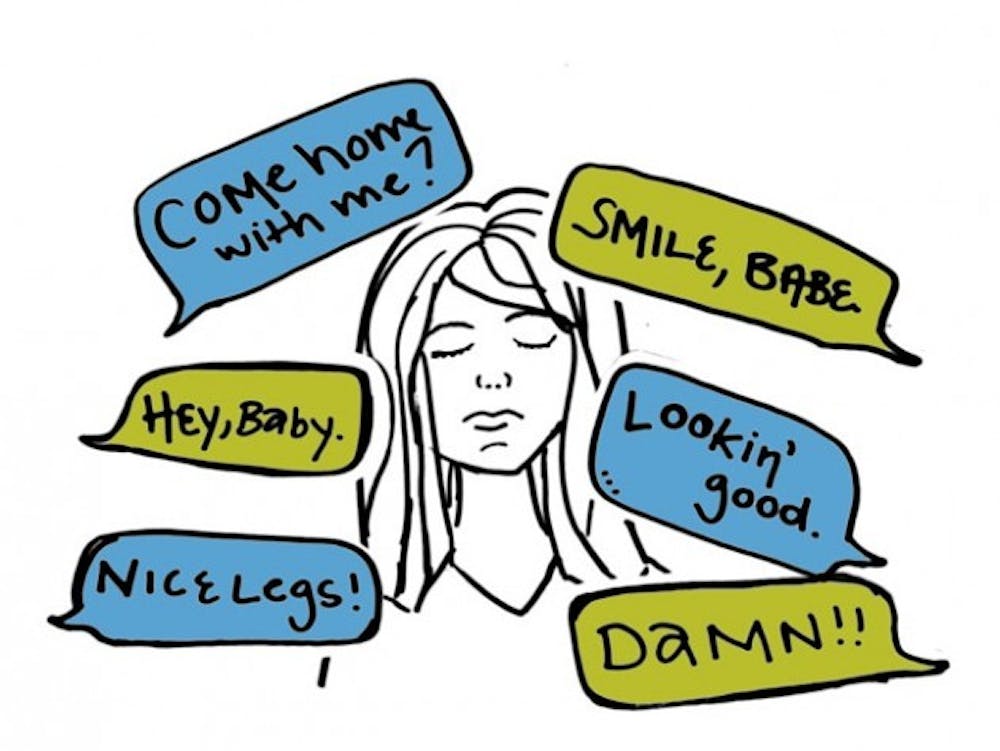

In the video, multiple men walked and catcalled with Roberts for an extended period of time. At one point, a man walked alongside her for almost five minutes. Some of the men said things like “beautiful” and “sexy” and would follow with angry remarks if Roberts did not respond.

“I have rarely, if ever, seen a man get ‘catcalled,’” Nesbitt said in an email. “[Women] are looked at as more of an ‘attainable prize’ than a person with feelings, emotions, etc. In many cases no means no, and no response means leave me alone.”

Winter sees “signs of confusion” in the men of the video and worries they are unable to “tell the difference between being aggressive and being friendly.”

Anne Marie, a graduate student in global gender studies and treasurer of UB Society of Feminists (SoFem), has worked with Hollaback! before. She does not really know if “we’ll ever be in a position to end street harassment.”

She said harassment is not as much about sexuality as it is about power. Rather, the issue is when women are alone in public places, this is somehow threatening to “some masculinities,” she said.

Winter does not think the men who catcall mean to be hostile.

Some men do not understand these harassments are a “kind of aggression,” because it is “part of a culture, which men are not socialized to understand the difference between being friendly, being aggressive, being insulting and being kind,” Winter said.

Marie doesn’t know what the actress might have been feeling, but admitted her past experience of harassment made her angry and involved in pointless arguments. If a woman responds to a harasser, she said it could escalate into a “yelling match” where the harassers don’t believe they have done something wrong.

“You feel really angry because there is nothing you can do really,” Marie said. “It’s totally a no-win situation.”

Some criticisms of the video were racial politics that may or may not have been involved because of editing.

Christine Varnado, assistant professor of transnational studies, said the video reinforced “the false idea that street harassment usually or mostly happens to white women.”

Tiffany Vera, a junior psychology major and co-chair of UB’s Black Women United, said the video has good intentions, but it perpetuates negative stereotypes of minority men.

“By only showing minority men cat call to the Caucasian woman, they are perpetuating the ‘Black Brute’ stereotype,” she said in an email. “However, in actuality, all men of every race and class cat call to women everyday.”

Marie, however, said the video editing may not have intentionally chosen to only include minorities catcalling, but she agrees there is still a problem of only showing minority races regardless.

Ivan Fruehan, a junior media study major, said he felt the video placed anything who was a “racial minority or not very good-looking” in a group of “creepers.” The video was “lumping people who greet her with people who try to violate her,” he said.

Fruehan said the “hollering” seemed out of proportion, but he would not “holler” himself.

Varnado said there is a robust community-based movement against the street harassment that happens to black and Latino girls and women, as much as it happens to white women.

“I actually think that women of color are recipients of a lot more hostility, violence, aggression and sexual exploitations,” Winter said. “I think it is geopolitics that women of color tend to be more vulnerable than white women.”

Noelle said having a wider variety of races in the video would have “elevated” the video.

Marie advises if situations are safe, you should say to the harasser, “that is harassment and I don’t really like it.” If harassers try to argue back, she said to just leave it at that and walk away. There are, however, other creative methods to respond, like “comedy or do something strange, that catches the harasser off guard,” she said.

Marie said catcalling can be “terrifying” for sexual harassment victims, especially during unwanted incidents in public where a victim has been yelled at, followed and groped.

email: news@ubspectrum.com