Christine Schaefer remembers “stomping around the tree farm for hours” with her family on the hunt for the perfect Christmas tree. Her father would stand next to a selected tree, reach his hand up and announce whether or not it was the right size.

Diane Christian’s father was not allowed to take down the Christmas tree until Valentine’s Day. Once, he tried, but Christian, now a SUNY distinguished teaching professor in the English department, cried so hard he was forced to put the tree back up.

For David Schmid, an associate professor of English, Christmas holds no religious significance because he’s an atheist, but it’s still a time to “eat too much and watch bad movies” with his family.

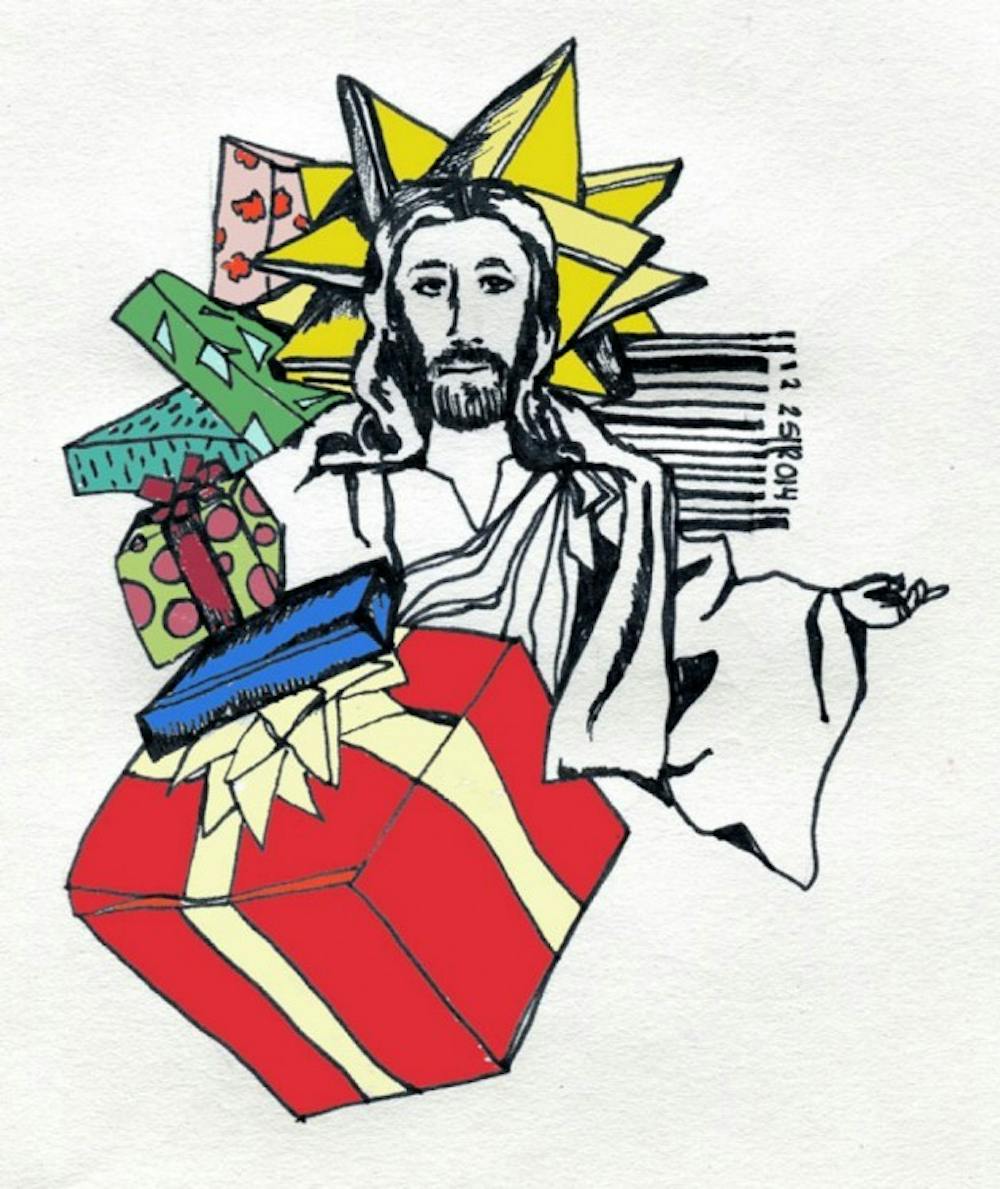

For some, there is a tension between the religious core of Christmas and the consumerism associated with it. This winter holiday season, it is predicted that total holiday spending, which includes entertaining at home, holiday clothes and decorations, will increase to $1,299 per household, up 13 percent from last year, according to Consumer Affairs. It is predicted that people will spend 9 percent more on gifts this year than last bringing the total to $458, from $421.

Christian and Schmid both said that the tension between consumerism and religious observance has existed for a long time for American Christians.

“My impression is that for the vast majority of Americans, there is no serious conflict between the religious meaning of Christmas and consumerism, not least because in this country consuming is its own religion,” Schmid said in an email. “I think people may sometimes pretend concern, but it’s not something that keeps them up at night!”

Christian said she has seen a change in how Christmas is celebrated and thought of in society since she first entered a convent in 1961.

“I think the religious element is much diminished and the consumerism is accelerated, but I think it’s always more complicated than it seems,” Christian said in an email.

During her eight years as a nun, Christian especially loved Christmas music and going to chapel at midnight, but she recognized the “strain between religious observance and commercialism.”

“I think this has always been a very real and appropriate tension,” she said.

Schaefer, a senior history and German major, said the meaning of Christmas has not been affected by consumerism.

“Semantics can change but that doesn’t change … what the holiday is all about,” Schaefer said.

Although people may not see Christmas as still being ultimately a religious holiday, she said, “holiday means holy day” and the word Christmas is a combination of “Christ” and “mass.” The religiosity of the day is clear in its name for Schaefer. Because Christmas is, at its core, a religious celebration, the various meanings people associate with it do not change that, Schaefer said.

In a mid-fourth-century Roman almanac, Jesus’ birth date is listed at Dec. 25 – now celebrated as Christmas Day, according to Biblical Archaeology. Celebrations of the holiday began between 250 A.D. and 300 A.D. and feasts on Dec. 25 likely existed before 312 A.D.

Consumerism can “encroach” on the religious celebration of the holiday, Schaefer said. For example, she said it must be stressful for parents who have to be aware of how much money they are spending on each child and to make sure each child receives an equal number of gifts.

This year, shoppers are expected to purchase 13.4 gifts, up from 12.9 gifts last Christmas. The amount of gifts bought per person reached its peak in 2007 at 23.1 gifts, according to Consumer Affairs.

One Christmas, Schaefer said she received “a lot of books and was kind of annoyed about it.” But her Catholic sentimentalities kicked in and she felt bad about being annoyed. Even at a young age, she felt Christmas meant much more than just receiving presents.

As a child, she participated in a Christmas pageant and sang in the angel choir. Although the garland halo was itchy, she said, the pageant reminded her of the meaning of Christmas.

Richard Cohen, a professor of philosophy and director of The Institute of Jewish Thought and Heritage, celebrates Chanukah and recognizes that gift giving is part of the “happiness” the holiday celebrates.

“[Chanukah] celebrates a military victory of the few against the many, the weak against the strong – certainly a theme for happiness,” Cohen said in an email. “And it celebrates the re-dedication of the Temple in ancient Jerusalem. Again a cause for happiness. So if ‘buying and giving gifts’ makes people happy, it is not in great conflict with the ‘religious core’ of the holiday.”

When Christian married Bruce Jackson, a SUNY distinguished professor and a James Agee professor of American culture in the English department, she helped raise his Jewish children. She said the children wanted to celebrate Christmas because of the tree, the lights and the presents. Christian said she “still hear” Jackson’s daughter, Rachel, asking for a Christmas tree.

Like Christmas, Chanukah is celebrated during the winter season.

Chanukah lasts eight days and celebrates the Jewish army defeating the Seleucid army. The Jewish army drove their enemies from the Holy Land and reclaimed the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. When they made it back to the temple to clean up the destruction caused by war, the Jewish army lit an oil candle. There was only enough oil to last one night, but it burned for eight days.

“My stepdaughter Rachel said when she was 3 that she wanted to be a Christian because being Jewish meant you couldn’t have a tree and gifts and lights,” Christian said in an email. “I told her how wonderful it was to be Jewish, how incorrect her reading was. She made paper ornaments and put them on a rubber tree to make us a Christmas tree. … Now she’s the mother of a 3-year-old, raising her boys Jewish, but accommodated.”

Schaefer’s family has a ritual for opening up gifts called the “pickle ornament.”

On Christmas Eve, her father hides a pickle in their Christmas tree. In the morning, the first person to find the pickle gets to open up a gift first. Then, the next oldest person gets to open a present and so on.

For Schaefer’s family, opening up Christmas presents is “a lot of sitting around and talking with each other.”

Schaefer said Christmas is a time when people “start to see the good more,” regardless of how they celebrate the holiday.

email: features@ubspectrum.com