It's easy to forget that everything we use, at one point, has been invented. The first telephone was invented by Alexander Graham Bell. The first light bulb was invented by Thomas Edison. But equally deserving of credit are the less-renowned others who create the everyday objects that most take for granted.

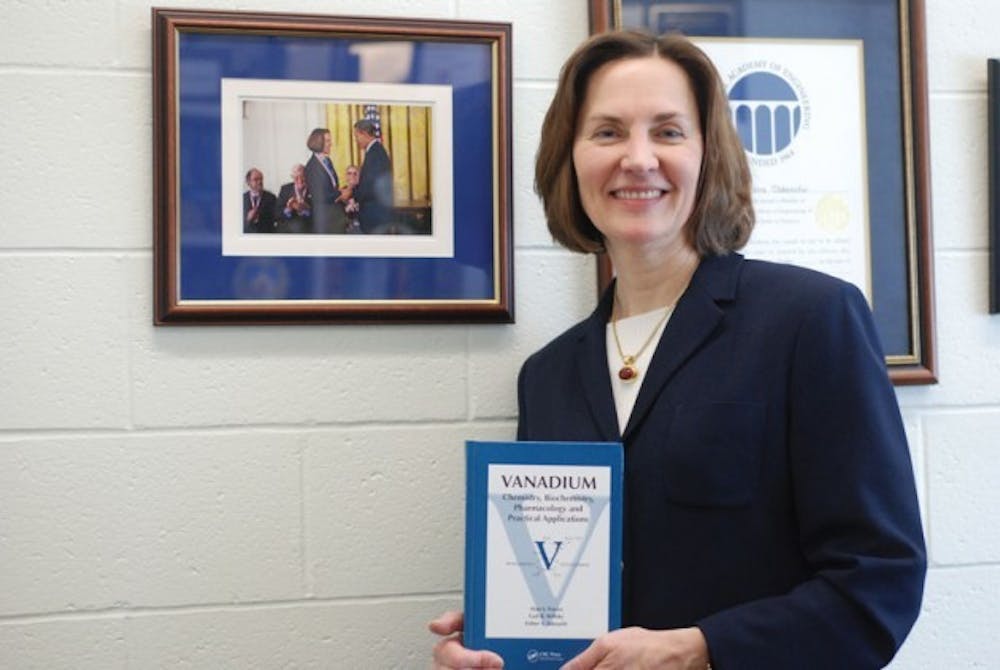

SUNY Distinguished Professor Esther Takeuchi is one of these inventors. She developed a small and durable battery that is now routinely used in pacemakers and saves people's lives every day. This May, she will be the 20th woman inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame for her life-saving innovation.

"It is a tremendous honor to be considered among the other people who are in the [NIHF]," said Takeuchi, who is also a Greatbatch Professor of Advanced Power Sources. "It's a very elite group of people and I'm really honored to be counted among them."

The Lithium/Silver Vanadium Oxide battery is just one of the 148 patents owned by Takeuchi, who is a faculty member in the departments of chemical and biological engineering, chemistry, electrical engineering, and biomedical engineering.

Implantable device technology is now a multi-billion dollar business. Over 300,000 pacemakers are implanted each year in people suffering from cardiac arrhythmia.

Patents like Takeuchi's and others in the National Inventors Hall of Fame are often overlooked because they have become so engrained in everyday life.

"We go through every day without realizing that the contributions of these inventors have shaped our lives," said Rini Paiva, spokesperson for the National Inventors Hall of Fame. "Esther Takeuchi is fitting of this description."

Since coming to UB in 2007, Takeuchi has added two more patents to her already impressive list, which primarily focuses on energy storage. The first patent was for her research that made it possible to increase battery efficiency while decreasing battery size. The other is for finding a way to make high-purity batteries in an industrial-scale process.

"We're working on batteries that are big or small, in the body or out of this world," Takeuchi said. "Some can be used for human implants. Some can be coupled with renewable energy technology. It's an exciting time to be involved in energy storage."

Induction into the NIHF involves a lengthy process. Inductees must hold a U.S. patent, receive nominations, and conduct their own research. A list of candidates is then presented to an inductee selection committee, which makes a decision after an all-day meeting discussing the candidate's body of work.

"[The committee] makes its decision specifically looking for work that moves society forward and has a life-changing impact," Paiva said.

There are currently 460 inductees, both living and dead, in the NIHF and only 19 of them are female. To Takeuchi, this means that there is plenty of potential left that can be implemented by those willing to showcase their innovation and creativity.

"We have an opportunity to encourage different groups of people to participate in innovation and the discovery process," Takeuchi said. "Each person brings a unique perspective to life and the world…the more [participants in research and innovation] the better, not just women but all types of people."

Other inventors being honored in this year's induction include George Davol, who patented the first digitally operated robotic arm, and Steve Sasson, who invented the first digital camera in 1975.

The National Inventors Hall of Fame is a non-profit organization established in 1973 by the U.S. Patent Ad Trademark Office and the National Council of Intellectual Property Law Association.

This year's induction ceremony will take place on May 4 at the historic Patent Office Building, now the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Portrait Gallery, in Washington, D.C.

Email: news@ubspectrum.com