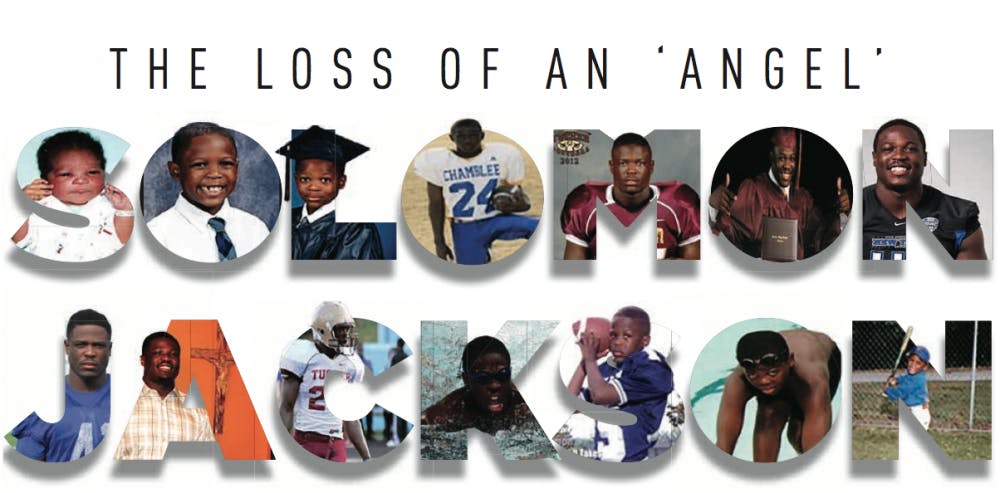

Steven Jackson lost his son Solomon, a UB football player, nearly two years ago and the hurt still sits heavy. Sometimes, on his way home from work at UPS in Tucker, Georgia, he drives to Solomon’s former high school, parks in the parking lot and cries. He remembers driving Solomon, who had perfect attendance, to and from school for four years.

He’s a big man and not a crier. But as he stares at the Tucker High football field and thinks about the glory days when his boy dominated the football field, won medals in the swimming pool and wore the high school prom king crown, he breaks down.

The grief Jackson keeps tight inside pours out.

It came out during Homecoming weekend last month, too, as he returned to the UB campus and talked to Solomon’s teammates, coaches and Jarrett Franklin, who this year wears No. 41, Solomon’s old number, on his jersey. He’s proud the team is carrying on and that the players dedicated the season to him. He feels Solomon is a part of it. He just wishes things were different.

In February of 2016, Solomon became the first UB athlete in team history to suffer a death that was apparently related to football. Roughly two years later, his family and members of the football team are still grieving. But they also still feel Solomon’s presence in their lives.

Jackson’s grief is part parasite, part friend. It eats at him––but it also nourishes him.

That’s why he came back last month.

He imagined Solomon, walking around the campus…

“He’s still out there, you know,” Jackson said. “His spirit is still there.”

Spirit of Solomon

Jackson remembers the way the family rejoiced when a UB scout recruited Solomon to play defense. All his sons had been born with big bones and football in their blood. Solomon chose No. 27 in high school, the number his big brother Sterling wore at the University of Hawaii. He moved on to No. 41 at UB.

His family couldn’t have known then what the future held.

On Feb. 22, 2016, their 20-year old, 6-foot-1, 229-pound boy collapsed at a UB conditioning practice at the North Amherst Recreation Center. The redshirt sophomore defensive end never stood back up. He died seven days later in the hospital, without ever speaking a word.

Jackson says his son died due to natural causes. The family declined to provide the autopsy report to The Spectrum. The Erie County Medical Examiner’s Office only releases autopsy reports to next of kin.

On that tragic Monday night, Jackson got a phone call from the trainers. Solomon had collapsed, they told him. The family rushed to Buffalo.

“For some reason, something hit me [when they called] and I asked what in the world was wrong––Solomon of all people, probably in the best shape of anybody on the team, biggest and strongest––in great shape and then they called,” Jackson said. “So I don’t know what was going through... my mind...I was breaking down at this point.”

UB handled the death quietly. The trainers hurried Solomon to the hospital, but the school did not make any announcements. The Spectrum tried to attend a memorial service for Solomon last February, but was told press wasn’t allowed.

The family isn’t hung up on what caused his death. They accept it as fate and, being religious people, as God’s will.

“We don’t understand it,” Jackson said. “We don’t ask God why. Solomon had so much more life to live and give. He was an angel in my life.”

Now, 22 months after Solomon’s death, his mother still sleeps and eats unevenly. She’s not caught up with what killed him. She just misses him. She misses his voice and saying his name. So she’s found ways to compensate. When she or Jackson open their front door, they call out to their son, saying, “Solomon, I’m home.”

Solomon’s 15-year-old sister, Solange, seven years younger than Solomon, was Solomon’s closest sibling. She knows he’s gone, but prefers to think of him as “off at college” and speaks about him in the present tense.

She and other family members insist that they still notice Solomon among them. One night, Solomon’s brother, Sterling, awoke, cold, on the sofa and said he could see Solomon’s silhouette, picking up a blanket to cover him. Solomon’s aunt, who gives speeches across the nation, often sees Solomon sitting in the crowd.

“It has just been a lot for the family to move on––it’s just not as easy as people think it is,” Jackson said. “God doesn’t make any mistakes. You know what he did? Solomon beat us to heaven. God called him home. He needed him more.”

Jackson goes to Solomon’s grave every Friday. Solomon’s mother visits on holidays.

“I know he’s not dead,” Jackson said. “His spirit is here. His spirit is at Tucker High School. His spirit is in Buffalo.”

Every holiday, the family mentions Solomon in prayer, and Jackson said it’s as if Solomon were there.

Tragedy on the field

His friends called him “Solo” for short and say he was resilient and joyful and expected more of himself than the coach did. Whenever he was knocked down, he jumped back up, determined to improve. That’s why no one could believe it on that February morning when Solo fell over and didn’t get up, his teammates said.

The team had just finished a practice.

As trainers hurried to the side of the football field, everyone heard Solomon breathing heavily.

“We were thinking, ‘He’s Solomon. He’s a tough guy. He’s just tired or probably didn’t eat before,’” said Jamarl Eiland, a Bulls wide receiver and friend of Solomon’s. “Solomon was such a strong guy; nothing ever defeated him. So about 10 minutes later he was still laying on the ground; all of us were confused and worried.”

Eiland said it was the first conditioning practice of the season and it was a “tough, non-stop” workout. There were stations of hurdles, running, drill work and agility testing. Boise Ross, who played receiver for the Bulls and was Solomon’s roommate, recalled the practice was just like any other.

Eiland said the team was stretching after finishing a run.

“Everybody got silent. Everybody dropped down to their knees and prayed for him,” Ross said. “As soon as you realize it’s taking longer than usual just to get up and for him to be OK, because usually Solomon always popped back up, it got serious.”

The trainers rushed Solomon to Buffalo General Medical Center.

“Never did I imagine I wasn’t going to see him after that,” Eiland said.

Coping with the loss

The last time Solomon’s parents spoke to him, they video-chatted him the day before he collapsed. Jackson doesn’t like to talk about it.

Solomon’s room still looks like it’s waiting for him to come home. His parents go in a few times a week and gaze at Solomon’s swimming and football trophies. Jackson was an all-state swimmer and an all-county football player.

“People come in this house and they say they feel Solomon and they feel he is at peace,” Jackson said.

Solange tries to avoid Solomon’s room. Before, she wouldn’t go in unless he told her she could. She feels it would be a sin to go in now. She said she would feel like Solomon was yelling at her.

Solange mostly refuses to talk about Solomon and sits in the car at the graveyard. She turns up the radio and pretends the family is visiting someone she doesn’t know. Her family has put her into therapy in the past.

When she thinks about Solomon, she thinks about the trampoline and about how he would jump with her for hours. Then they would lay down on it and talk about life. He had a gentle way of easing her mind. Solomon used to babysit her and take her on bike rides. They liked to cook food together and even when they burned the pizza, it still tasted good. He taught her not to get anxious about the small things and to enjoy what she had.

He taught her to skip a rock, and together, they found a “hidden” lake. It was their special place. When they were together, she felt light and like anything was possible. He was her hero.

Solange tries to distract herself from the loss by cheerleading and keeping a 4.0 grade-point average. She said she doesn’t have friends and goes to school to do what she needs done. She sometimes has trouble sleeping and hallucinates.

“I get this weird sense of someone being there, but then I fall asleep and it’s over,” Solange said. “I felt somebody pick me up and bring me back to my room after I fell asleep on the couch. I legit felt like it was Solomon, but I know it couldn’t be possible even though it really did look like him.”

Solomon’s parents still cook his favorite meals: spaghetti with meat ragout sauce, Polish sausage, ground beef and turkey.

Growing into himself

Jackson said Solomon was a chubby baby and ate a lot of food and “grew into his muscles.” Solomon would call his dad from UB sometimes to perfect his seasoning on his steak, which always made his dad grin.

Jackson’s elementary school bus driver told Jackson’s parents how often Solomon spoke about how much he loved being with his family – from taking trips to their timeshare in Orlando to go to Disney World over break, or spending Christmas with loved ones.

“This kid talked about his family all the way home, and he does it every day,” the school bus driver told Jackson.

Courtesy of the Jackson family: Solomon Jackson (second from left), stands with his family at his last family picture at home on Dec. 30, 2015.

But over the first five years of Solomon’s life, Jackson spent time in Germany, Korea, Egypt and Israel while he served in the U.S. Army.

Jackson, a 21-year military veteran, had five years of service left when Solomon was born. He had a pass to come home every weekend to spend time with his family.

On the weekends, he coached Solomon, his siblings and his friends in football. Solomon started playing football at 5 years old.

As a coach, Jackson was harder on Solomon than any of the other teammates, but Solomon never seemed to mind.

“He had no enemies. He treated everybody the same no matter of the color of your skin or how big or small you are; you know, he was truly an angel,” Jackson said. “This kid just loved life. He held no grudges; he would just let things come and go.”

Jackson remembers how much Solomon loved Batman because of his strength and bought him a Batmobile on July 24, 2016, which would have been Solomon’s 21st birthday.

Solomon’s last time home was for Christmas, but he left early to come back to UB to meet the new recruits.

Initially, Solomon didn’t want to go to college too far from home. But once he met former UB football stars Khalil Mack and Brandon Oliver, he accepted the school’s offer without looking back.

Mack and Oliver – who now play in the National Football League – mentored Solomon and showed him how to be a serious player, Jackson said.

Jackson developed relationships with Mack and Oliver and they still call him on the phone.

“That’s why the players called me ‘Pops,’ because I was the Pops for a lot of them with fathers who didn’t come like I did,” Jackson said. “I was privileged and fortunate to be able to do that.”

Jackson took the players out to dinner and encouraged them during games. Solomon’s friends remember Jackson being at games and cheering them on from the sidelines. Eiland said he specifically remembers looking to the sideline during the games and seeing Jackson shouting, “All for one.”

Jackson misses those games and says he still has a strong affinity for UB.

“UB will always be home. The team will always be a part of us,” he said.

Eiland recalls the moment when he and Solomon had just gotten their first helmets in the locker room and Solomon broke down and cried.

“He was just thankful. It was always a dream for all of us to get to that point,” Eiland said. “When he got to the realization that he actually completed that goal, that’s when he broke down... I just remember being surprised that he was that proud at that moment, but I never thought someone would cry because they were so proud.”

It is comforting for Jackson to still be in contact with Solomon’s friends even though it makes him sad his boy will not be able to graduate with them. He said he talks to them a few times a week.

Jackson listens to gospel music every day and cries when he hears psalms about giving one’s life to God.

Every Friday, Jackson goes to Solomon’s grave and talks to his son. Other times he sits next to the grave and cries. Sometimes he sits and prays.

“It has not been easy. Every day is different,” Jackson said. “There’s not a day or millisecond I don’t think of Solomon. It’s still an open wound.”

Keeping strength on the field

Many UB football players said they had a tough 2016 season after the loss of Solomon, but they have gained strength from his death.

Ross felt Solomon with him as he wore Solomon’s number, 41, last season.

“My mentality is honestly Solomon Jackson,” Ross said. “He’s always worked hard. He’s always had a good spirit, and so every time I come out here now, I feel like, ‘Why not be happy and why not be jovial about the situation that I’m in, because it can end at any moment.’ So that’s what really what drives me.”

Ross said Solomon hated losing. But he remembers Solomon’s smile and positive attitude toward life the most.

“Every time I think about him I think about how he walked through the halls or how he walked to practice, how he carried himself. He was a good spirit always,” Ross said.

The elder Jackson said it is not just a privilege for the family to have Solomon’s number worn, but he said it says something about the player who wears it.

“[Boise, Jarrett and Solomon] all came to UB like brothers,” Jackson said. “They came on scholarship and started school together and now they would graduate together. It is very, very touching for me to see.”

Eiland said he talks to Solomon in his head before games to stay focused and motivated. He feels Solomon is watching over him.

Jackson called Solomon “a tank” and said he could get through anything. He said Solomon would beat himself up after games because he was his own “strongest critic.” Jackson said Solomon never thought he played the best game.

Franklin, who wears No. 41 this season, said Solomon’s death was one of the hardest things he has dealt with.

“I remember the day we found out. It felt like a dream. I felt like it was a nightmare, and I just needed to wake up from this nightmare,” Franklin said. “Days and weeks passed by, and I kept thinking, ‘This can’t be happening. It’s not real.’ And you know, it just pained me. I remember the worst part about it was me calling my dad and breaking the news to him because you know, I broke down and started crying.”

Franklin said losing last season was disappointing. But he feels Solomon’s spirit on the field, and it helps him move forward.

His first impression of Solomon was his Southern accent and his genuine smile.

“Honestly, I feel like his death is the hardest thing many people on the team have gone through,” Franklin said last year. “So this season going the way it has, we can’t say this is the worst we’ve ever seen because we’ve experienced the worst thing that’s ever happened to us. So this is just another test and we have to push through this test and try to build off of this.”

Franklin feels most of the team has been “playing for Solomon.”

“What keeps me going, if I mess up a play, I would think to myself, ‘Well, Solo would keep his head up,’ or if I’m not hustling to the ball fast enough, ‘Well, Solo doesn’t have the opportunity to,’” Franklin said. “All the opportunities Solo doesn’t have anymore – we have to take advantage of those opportunities because we’ll never know when our last game is.”

Jackson came back to UB on Oct. 8 to see the game against the Western Michigan Broncos. He stood on the sidelines the entire time with the coaches to root the players on.

“I’ve built a lot of relationships with these young men and Solomon’s coaches since his passing and it’s relationships that are going to last the rest of my life,” Jackson said.

He pictured Solomon, who would have been graduating this year, on the field and felt everyone was playing for Solomon. He heard Solomon’s voice during the game, saying to his teammates, “Move forward,” and, “Don’t worry about it. We need you. We still got this.”

There is still a chair in the defensive locker room with Solomon’s jersey that no one sits in. There is an “All 41” sign painted over the entrance to the locker room, and his No. 41 is painted twice on the field.

“Solomon may be gone, physically. But, as Jackson says, “his spirit will always be in Buffalo, as well as in Georgia.”

When Jackson looks back on his son’s life, he is honored to have known him for 20 years.

“That’s pretty much it in a nutshell, Solo’s life, his young life,” Jackson said. “But I wouldn’t change nothing for the world.”

Credit: THE SPECTRUM/Katie Kostelny: Solomon’s father, Steven Jackson stands on the sidelines at the Homecoming game last month. He stood with the coaches, rooted the players on and imagined Solomon on the field.

Hannah Stein is editor in chief and can be reached at eic@ubspectrum.com