Thousands of survivors of sexual assault and harassment are speaking up and sharing their stories to spread awareness through a five-letter phrase: “me too.”

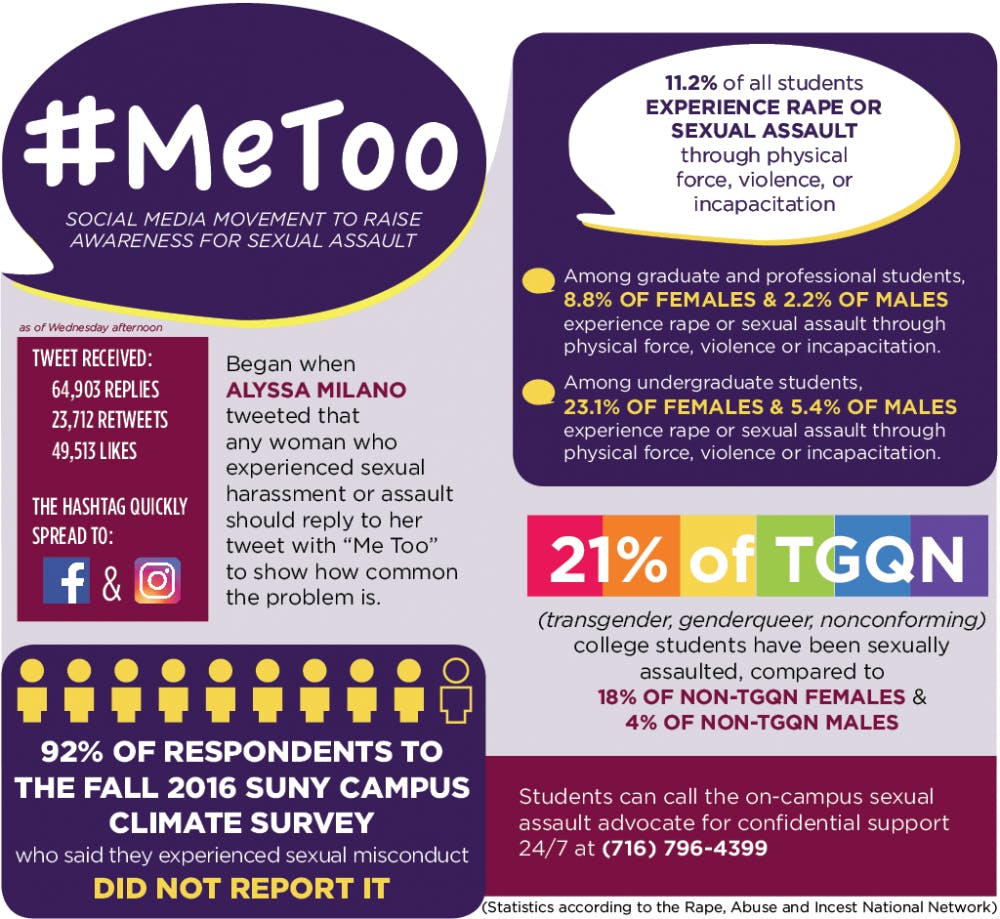

The #MeToo movement originally started 10 years ago when black activist Tarana Burke created the phrase as a way to connect with other survivors, especially other women of color who had experienced sexual violence. Actress Alyssa Milano posted a tweet Sunday night asking any woman who has experienced sexual harassment or assault to reply to the tweet with “Me Too” in order to raise awareness about the magnitude of the problem on social media.

Since Sunday, Milano’s tweet has received 64,903 replies, 23,712 retweets and 49,513 likes as of Wednesday afternoon. The movement quickly spread to Facebook and Instagram, dominating social media feeds with the hashtag. Some survivors chose to go into detail about their experiences. Others just posted the hashtag alone. Sharon Nolan-Weiss, UB’s Director of Equity and Inclusion and Title IX Coordinator, feels the hashtag is a way for survivors to discuss the issue without needing to go into detail about something traumatic. Some UB student survivors find the hashtag as an important conversation starter. Others see it as triggering for victims.

More than 11 percent of all college students experience rape or sexual assault through physical force, violence or incapacitation, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network. Among graduate and professional students, 8.8 percent of women and 2.2 percent of men experience rape or sexual assault. More than 23 percent of undergraduate females and 5.4 percent of undergraduate males experience rape or sexual assault. And 21 percent of transgender, genderqueer and gender nonconforming college students have been sexually assaulted, compared to 18 percent of cisgender women and 4 percent of cisgender males.

“[The #MeToo movement] is one of these things that just captures a certain feeling that’s been bubbling up,” Nolan-Weiss said. “Most women, and a lot of men too, have experienced some type of unwelcome sexual experience across the course of their lifetime.”

For some people, this starts early, she explained.

“If you ask any woman when’s the first time you experienced street harassment, you’ll have a lot of women tell you it was at age 12 or 13 or sometimes even 9 or 10,” Nolan-Weiss said. “These experiences are very common but people don’t talk about it.”

She thinks this conversation is important because sexual assault is under-discussed and underreported; 92 percent of respondents who said they experienced sexual misconduct in the Fall 2016 SUNY Campus Climate Survey did not report it.

“We tend not to talk about it or we’re discouraged from talking about it by society and it’s a way of sort of relating how common this is,” Nolan-Weiss said.

While the original post was targeted specifically at women who have experienced sexual harassment or assault, some posters have changed the wording to be more gender neutral and inclusive. Nolan-Weiss believes this is a good move. Gender non-conforming students experience sexual violence at a rate about twice that of their cisgender peers, according to Nolan-Weiss. She believes silencing those voices is neither fair nor productive.

“The way I see it, the #MeToo is people relating their own experiences and I don’t know that we can silence somebody,” she said.

She also feels like it’s important for male victims to have a platform to share their

experiences.

“Among men there’s a lot in our culture that tells them that you can’t be a victim or you can’t speak up… it’s not something that is generally encouraged or accepted or understood,” Nolan-Weiss said. “So I think being given an outlet to speak up is very important for them.”

While Savannah Fleming*, a graduate student, feels the #MeToo movement has sparked an important conversation, she also finds it triggering.

“I see the point but I think it’s affecting survivors more than anything,” Fleming said.

“We’ve already been screaming out; this isn’t going to make people listen if they already know. It might bring awareness to some but I almost feel like the cost is greater than the worth.”

The hashtag brings back painful memories for Fleming. She said it reminds her of how her ex was abusive while his friends enabled him

“It reminds me of when I told my ex that our friend molested me,” Fleming said, “Our friend used my emotional state to get [sexual] things from me, and I was called a slut for that.”

Nolan-Weiss said she can see how the hashtag could be triggering for victims.

“I can see how that can be the case, because if you’re on Facebook and you’re being exposed to [people talking about] situations of sexual harassment and sexual assault, in a way it feels like you can’t escape from it,” Nolan-Weiss said. “I can see that being very difficult to get through.”

Fleming believes most people are already aware of the prevalence of sexual assault. The real issue is that society doesn’t listen to victims, she said.

“It’s not that its hidden, it’s ignored. If you're not listening, why should I tell?” Fleming said. “If no one will understand or change their behavior, what can a survivor do?”

Sophomore Alexis Donahue* is a sexual assault survivor who sees both positive and negative aspects to the hashtag. She agrees that it has opened up an important conversation, but is concerned that it places too much responsibility and pressure on victims.

“Victims are rarely acknowledged in the news, so hearing the outpouring of victims stories and support for victims has been a major stride for American culture, a culture that puts blame on victims of sexual assault and harassment,” Donahue said.

She acknowledged that many survivors feel empowered by the hashtag, but for her personally, it is not enough. She is happy to see such a huge, public conversation about sexual assault and harassment happening, especially in such a “victim-centered” way. However, she feels more emphasis needs to be placed on the perpetrators’ role in committing sexual violence.

“This is good, and I’m all for it, but the conversation needs to expand to put blame on the people who perpetuate rape culture and those people who sexually assault and harass,” Donahue said.

She feels it is time to call on the people who hurt victims and caused this pain and trauma in their lives.

“These people need to feel personally accountable for the lives they have hurt,” Donahue said.

Nolan-Weiss has also heard similar criticisms of the movement.

“Another backlash I’ve seen toward this hashtag is the idea that why is it always women that have to speak up,” Nolan-Weiss said. “And like I said, some men have also shared their experiences, but it’s just this idea of, why do victims always have to be the ones to educate everybody else.”

Nolan-Weiss also discussed another, less popular hashtag: "It Was Me.”

“There’s also an ‘It Was Me’ hashtag that’s going around and it’s interesting to read those as well. Because you know there’s people saying, why aren’t there people saying it was me and understanding that I didn’t know this at the time but this was the impact of my actions,” she said.

Nolan-Weiss also discussed resources that are available to students who experience sexual assault. The university has both reporting and support options, she explained.

Students who wish to report a situation can come forward to university police, the Title IX office or Student Conduct and Advocacy.

“And whether it happened months ago or a year ago, reporting can be a way to preserve your right to move forward; it doesn’t mean that you have to move forward at that time but we definitely encourage that,” Nolan-Weiss said. “And when someone reports – even if they don’t want to move forward – it helps us to spot a pattern.”

The university also offers support resources to assault victims.

“Our university counseling services is a confidential resource, so if somebody is not sure that they want to move forward and want something absolutely confidential, counseling services is a great place to go,” she said.

In addition, students have access to a crisis support advocate.

“The advocate will meet a student in their dorm room, or wherever on campus that’s comfortable for them and will be their advocate,” Nolan-Weiss said. “So it’s completely confidential and they can help the student with support options, with other resources.”

The advocate can explain what will happen if a student chooses to report, and can make confidential inquires on behalf of the student.

Overall, Nolan-Weiss sees the hashtag as a positive movement that has sparked an important discussion and helped survivors feel less alone in their struggles.

“I think [the hashtag] has really opened up a conversation and it’s made people feel not as alone,” Nolan-Weiss said.

*Editors note: Names have been changed to protect victims’ identities.

Maddy Fowler is a news editor and can be reached at maddy.fowler@ubspectrum.com